Joe Biden’s first trip to the Middle East as president shunted aside his administration’s inaugural goal of building a foreign policy “centered on the defense of democracy and the protection of human rights.” Instead, Biden’s trip was centered on shoring up old relationships, extolling US-Israel ties, strengthening regional security architecture (mainly with Iran in mind), and genuflecting before Gulf oil autocrats who were very much expecting deference at a time of energy stress. In other words, Biden pursued an all-too-traditional agenda. The so-called “peace process” between Israel and the Palestinians—which would have been a major element of almost any presidential visit in years past—was barely an afterthought. In fact, differences between Biden’s approach to the region and that of his predecessor were hard to find.

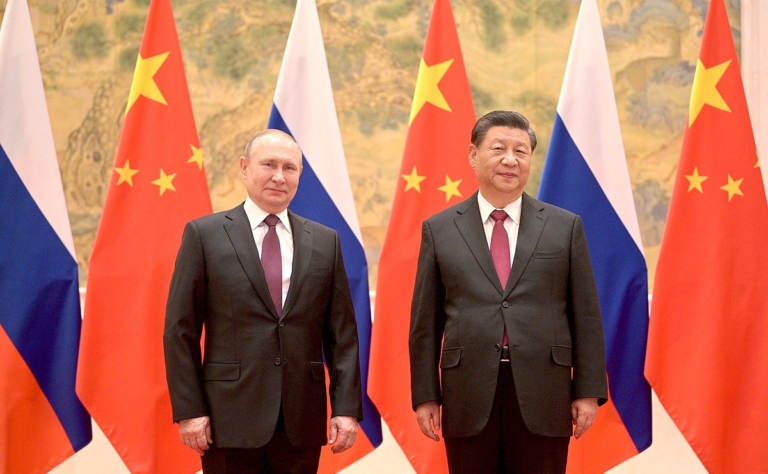

But one element did stand out: the launch of an ambitious quest to rebuff growing challenges to the US position in the region posed by Russia and China, both of which have gained significant influence in the last few years, largely at the expense of the United States. Military sales, security ties, expanding trade relations, and significant infrastructure investments by both countries have been major factors in the gains made by Moscow and Beijing. So has their willingness to overlook—and even encourage—human rights violations and political repression, which is not only meant to keep democracy at bay but also to draw a sharp contrast with Washington and its penchant to raise these uncomfortable issues.

Biden made clear during his trip that the United States has no intention of abandoning the field to its main rivals. Speaking at the GCC+3 summit convened by Saudi Arabia in Jeddah, the president declared that the United States “will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran. And we’ll seek to build on this moment with active, principled American leadership.”

But despite this declaration, there is little evidence that Biden made much headway. To be sure, he confronted a difficult environment, with an Israeli government in chaos and Gulf leaders who sensed evidence of American weakness that could be exploited to advance their own interests. While the trip firmly placed the goal of countering Russia, China, and Iran on the US diplomatic agenda, the president has a steep uphill climb from here on out.

Israel: Ambivalence on Russia and China

Biden began his trip in Israel, where he was at pains to advocate for Russia’s strategic defeat in Ukraine. He was met with a certain amount of hedging and very few concrete commitments. The Israeli government—no matter who is in the revolving chair of governance—has resisted severe condemnation of Russia, largely because its own military activities in Syria appear to be dependent upon Russian permissiveness in the Syrian airspace controlled by Russian forces. Israel has refused entreaties to provide weapons to Ukraine, including effective anti-missile devices like its Iron Dome system. It has mainly confined itself to rhetorical support of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. But Israel’s politicians are also constrained by the views of its large Russian-Jewish population, many of whom remain hostile to Moscow given the repression that they suffered at the hands of the Soviets.

The result of these clashing interests has been, essentially, a stalemate. The current Israeli government has edged toward the western position, while declining to commit to more robust support of Ukraine. And the Biden visit didn’t do much to move the needle. It is unlikely that Israel will draw closer to Russia—Tel Aviv has healthy respect for the opinion of Washington on this score—but it still remains firmly on the sidelines as the Ukraine conflict progresses.

It is unlikely that Israel will draw closer to Russia—Tel Aviv has healthy respect for the opinion of Washington on this score—but it still remains firmly on the sidelines as the Ukraine conflict progresses.

Israel’s growing relationship with China, meanwhile, did not appear to be a significant element of the Biden trip. But it remains a major concern for the US policy community, particularly the Pentagon, which worries about China’s expanding role in Haifa, a key port of call for the US Sixth Fleet. Israel also has deep and extensive technology and trade ties with Beijing. As with Israel’s Russia relationship, the US and Israel seem to have agreed to disagree on China—and to keep the disagreement under wraps.

Saudi Ties with Russia and China Concern Washington

Saudi Arabia, however, is more than willing to test the new political space afforded by the appearance of American weakness. Driven in part by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s growing contempt for the administration and for Biden in particular (due in no small part to the president’s vow to make the kingdom a “pariah”), Riyadh has appeared eager to distance itself from its American partner. The kingdom responded dismissively to Washington’s requests to expand oil production to meet global shortages, partly because Saudi Arabia has little production capacity to spare. But it also wants to remain a driver of the OPEC+ consensus on oil production, in which Russia has cooperated closely with Saudi Arabia to manage supplies and prices. In fact, Riyadh recently doubled its imports of discounted Russian fuel oil to meet its domestic demands—even in the face of international pressure to crack down on Russian petroleum exports—thereby allowing the kingdom to sell more of its own oil supplies on the international market at great profit. It is clear that Riyadh is in no mood to do Biden any favors on this score.

Russian-Saudi military cooperation appears to be growing, although it is in its infancy compared to existing Saudi security cooperation with the United States.

Meanwhile, Russian-Saudi military cooperation appears to be growing, although it is in its infancy compared to existing Saudi security cooperation with the United States. Nuclear cooperation between the two countries also remains on track, with Russia participating in a tender to build reactors in the kingdom following the signing of a nuclear cooperation agreement in 2015.

Saudi Arabia has deepened its relations with China as well. The kingdom is now the chief supplier of oil to Beijing, and in 2016 the two countries declared a strategic partnership based on long-term energy relations; arrangements to allow China to pay for Saudi oil imports in its own currency, the yuan, rather than dollars, are proceeding. Military cooperation with China is trending upward as well. Riyadh has purchased drones and military aircraft from Beijing, and may be manufacturing ballistic missiles with Chinese assistance.

Moreover, China’s far-reaching Belt and Road initiative (BRI), a massive multi-region infrastructure and transportation scheme designed to expand China’s economic reach, includes Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt as sites of major development projects. Neither the Trump nor the Biden Administration have offered much of a counterweight.

While these concerns were certainly on the minds of administration officials while in Jeddah and were articulated publicly in a very general way by the president, they appear to have been drowned out during the trip by Washington’s concerns over oil supply and its eagerness to expand Arab countries’ diplomatic and security ties with Israel.

Moscow Making Progress with the UAE and Egypt

The Saudi-Russian relationship is of greatest concern to Washington, particularly in terms of the two countries’ close collaboration in managing oil output. But Russia’s ties with the UAE and Egypt have aggravated the administration as well.

Dubai has emerged as a safe haven for expatriated Russian wealth and real estate investment, as oligarchs have sought to escape Western sanctions. UAE officials have so far equivocated in discussions with the US aimed at encouraging the Emirates to crack down. Likewise, the UAE has sided with the Saudis and the Russians in its reluctance to expand oil production to meet international needs. Political ties between Abu Dhabi and Moscow are now so strong as to amount to an alliance in the eyes of some observers. One indication of this was the UAE’s February abstention during a vote on a UN Security Council resolution that would have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one that Moscow ultimately vetoed.

Dubai has emerged as a safe haven for expatriated Russian wealth and real estate investment, as oligarchs have sought to escape Western sanctions. UAE officials have so far equivocated in discussions with the US aimed at encouraging the Emirates to crack down.

Like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Egypt too has been drawing even closer to Moscow. Cairo has refused to strongly condemn the invasion of Ukraine, and recently hosted friendly talks with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov to discuss both Ukraine and regional issues, capitalizing on the warm personal rapport between Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Nuclear cooperation between the two countries has intensified with the start of construction by Russia’s Rosatom of Egypt’s first nuclear power plant, El Dabaa. Egypt’s arms purchases from Russia have also increased dramatically, much of it underwritten by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in line with their own gravitation toward Russia. All this represents a strategic challenge to US interests in a country that has been a vital partner to the United States for the last four decades.

Geopolitical Gamesmanship: Will It Pay Off?

These developments signify a strong desire in the Saudi, Emirati, and Egyptian governments to diversify their foreign policy ties and, no doubt, to spark a bidding war between Washington and Moscow for their allegiance and services. Biden’s trip did little to change minds or actions on this score. Despite the president’s avowal of continued engagement to counter Russia and China, most leaders in the region remain uncertain about US intentions, worry about the possibility of a geostrategic American pivot to the Indo-Pacific and away from the Middle East, and consider the US an inconstant partner and actor. Nothing that the president said on his trip or that the administration has done so far indicates that it has a far-reaching strategy to change this basic dynamic. Key Arab governments seem more than willing to keep playing the positioning game until and unless the United States throws some serious incentives—or disincentives—on the table.

Despite the president’s avowal of continued engagement to counter Russia and China, most leaders in the region remain uncertain about US intentions.

Iran and Russia Increase Ties

Biden’s trip did have an impact on Russian influence in the Middle East in one important respect: it appears to have spurred closer ties between Moscow and Tehran. On July 19, three days after Biden left the region, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei hosted Vladimir Putin for the latter’s first trip outside Russia since the Ukraine invasion began in February. During the visit—where Putin also met with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—Khamenei championed intensified long-term cooperation with Moscow against the West, and in particular against the United States. Khamenei subsequently issued a statement expressing his full support for Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, describing the Russian action as a justifiable response to the allegedly aggressive intentions of NATO.

These rhetorical salvos seem to be backed up by fresh signs of cooperation between the two countries. The White House claimed in July that Tehran had concluded a deal to send hundreds of weapons-capable military drones to Russia for use in Ukraine, and an unnamed administration official said that Iran has commenced training Russian soldiers in their use (a claim that both Russia and Iran deny). On August 9, Russia launched a new Iranian surveillance satellite from its Baikonur space facility in Kazakhstan. US officials believe that Russia will be able to utilize the satellite for at least some months and perhaps longer, which will provide Moscow with intelligence on Ukrainian targets.

A Different Approach

Having seen the importance the United States—at least publicly—places on countering Russia and China in the region, Egypt and the Gulf countries have little reason to stop flirting with Moscow and Beijing. Key Arab states likely anticipate additional US diplomatic missions to offer concessions and therefore aim to increase the chances of a diplomatic bidding war among the world’s three biggest powers. This, at least for now, is a smart game for Arab governments to play, but not so much for the United States.

As the twin crises posed by Ukraine and the pandemic recede—and along with them the need for the United States to ask for favors—Washington should try to reset the terms of these relationships by demanding a greater price for its support. This is eminently possible because US standing in the region, despite doubts and caviling from America’s regional partners, remains strong. Both Russia and China still lack the depth of strategic ties, the complex web of arms sales and military logistics, and the volume of trade and economic activity that has bound Egypt and the Gulf to the United States for decades. Neither Moscow nor Beijing, despite their growing military presence in the region, possesses either the capability or the desire to supplant the vital role the United States has long played as the guarantor of regional stability, particularly when it comes to Iran.

As the twin crises posed by Ukraine and the pandemic recede—and along with them the need for the United States to ask for favors—Washington should try to reset the terms of these relationships by demanding a greater price for its support.

Washington is thus in a good position to take a more assertive stance. Arms sales policies would be a good place to start. As it now stands, America’s Arab allies have little reason to believe that the United States will take meaningful steps to shape its military assistance and sales programs to meet anyone’s needs but their own. Despite the seriously strained bilateral relationship between Saudi Arabia and the US, the Biden Administration announced a $650 million arms sale package to the kingdom in November 2021, as well as a $3 billion sale of Patriot missiles to Riyadh and $2.2 billion in high-altitude missile defense for the UAE in August 2022. A first step would be to reconfigure US arms sales policies to consider the degree to which recipients maintain military ties to Russia and China, whose facilities and personnel in partner countries can pose intelligence threats to US operations and classified weapons systems. In addition, the United States should enforce its own laws regarding arms sales to human rights abusers, which in the short run may drive some Arab countries to instead purchase from Russian and Chinese suppliers, but which, given the deep entrenchment of US weapons systems in the inventories of the Gulf states and Egypt, may force some painful choices on their military establishments in the long term.

More positive incentives, such as the $1 billion in food security assistance for the Middle East and North Africa that Biden announced during his trip, would also serve to draw a contrast with the Russian and Chinese approaches, which tend to be focused on trade, technology, and military cooperation, a strategy that disproportionately benefits governments and economic elites. In this regard, a more substantial US focus on education, agriculture, and climate change initiatives would be impactful.

More positive incentives, such as the $1 billion in food security assistance for the Middle East and North Africa that Biden announced during his trip, would also serve to draw a contrast with the Russian and Chinese approaches.

In addition, President Biden should repeatedly and consistently confirm his global concept of the contest between democracy and autocracy. He should continue efforts to reinforce the line between democratic and democratizing societies and the burgeoning autocratic bloc led by Russia and China by fully engaging the Summit for Democracy as a standing institution dedicated to the preservation and advancement of democratic governance and human rights. This would provide an international forum for focusing attention on these issues in a way that the UN Human Rights Council, for example, cannot, and may put more pressure on America’s often ambivalent (and very often unhelpful) partners in the Middle East to choose which side they wish to be counted on. Such an effort could help reshape the dialogue between the US and its regional allies and reduce their political room for maneuver between the US and its main global rivals.

This will necessarily pose challenges. Will America’s Gulf partners and Egypt determine that the United States is a declining power and that the future of their economic development and national security therefore lies with Russia and China? And if so, does the United States still have a paramount interest in remaining as engaged in the region as it has before, especially if economic and security returns continue to diminish? These are tough questions indeed; but if the United States is serious about countering Russian and Chinese influence, they are questions worth answering. A more vigorous and comprehensive US strategy would be a good starting point.