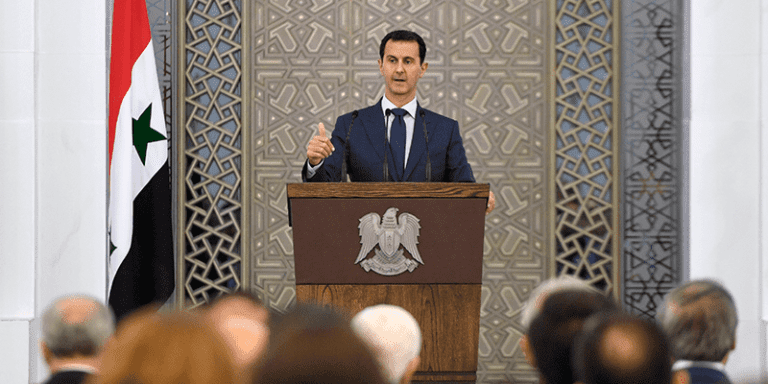

There are growing indications that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government is gearing up for a three-year plan to hunker down and solidify gains ahead of Syria’s presidential elections in 2021, when the regime might come under external pressure to undergo significant changes.

With no breakthrough envisioned in peace talks with the Syrian opposition, the Assad regime is laying the groundwork for the necessary conditions to reap the benefits of postwar Syria and strengthen control over territories recaptured in the last few years. This process is largely driven by Moscow and by domestic pressure to appease an anxious base increasingly dissatisfied with corruption and lawlessness.

This mindset was evident in the November 26 decisions that included a cabinet reshuffle of nine ministries, the transfer of the national reconciliation portfolio from a ministry to a commission, and the appointment of a new governor for Damascus province. While this is the third reshuffle of the 2016 cabinet (the first came in March 2017 and the second in January 2018), the scope and timing of these announcements are noteworthy and come on the heels of an overhaul of the Syrian regime’s bureaucracy with the aim of strengthening security control and redistributing wealth in postwar Syria.

The scope and timing of the last cabinet reshuffle are noteworthy and come on the heels of an overhaul of the Syrian regime’s bureaucracy with the aim of strengthening security control and redistributing wealth in postwar Syria.

Cabinets under the Syrian regime merely have regulatory functions, as key political and security decisions are controlled by the deep security state or the prevailing security establishment that runs the country. Assad regularly uses the cabinet reshuffle strategy to adjust the operational dimension of governing and absorb the public disenchantment with his regime. Personal connections with Assad or the deep security state as well as loyalty to the regime are key qualifying factors in selecting appointees for ministerial positions.

The Cabinet Reshuffle

The last cabinet reshuffle kept the 30-minister representation intact, with a balance of 19 ministers coming from provinces loyal to the Assad regime (Damascus and its suburbs, Latakia, and Tartous). Additionally, four ministers are from Aleppo and three are from southern Syria. As the regime base has shrunk significantly since 2011, key provinces such as Homs, Deir Ezzor, Raqqa, and Daraa are not represented in the cabinet. This regional imbalance reflects the lack of national legitimacy beyond the core base of the regime.

The first major move in the cabinet reshuffle was the long-overdue decision to remove Mohammad al-Shaar from running the interior ministry where, since 2011, he played a key role in suppressing anti-regime protests. He survived two assassination attempts: the July 2012 bombing of the National Security headquarters in Damascus and the December 2012 car bombing in front of the interior ministry. The public complaints about al-Shaar recently increased in the areas under the Assad regime’s control as the rate of corruption1 and lawlessness2 have grown under his reign. Al-Shaar no longer fits the anti-corruption campaign that Assad is currently claiming in order to quell the popular anger against widespread misuse of power by key figures in his regime.

Since last year, Mohammad al-Rahmoun, al-Shaar’s successor, ran the political security directorate; he came from the air force intelligence directorate where he coordinated with his Russian counterparts. As head of the political security directorate, al-Rahmoun reported to Assad directly instead of to the interior minister, and his investigation of al-Shaar ultimately led to the demise of the latter. Al-Rahmoun is loathed by the Syrian opposition for running ruthless detention centers. He is on the US Treasury’s 2017 sanctions list of Syrian officials accused of using chemical weapons against civilians in 2014-2015.

Al-Rahmoun appears to be tasked with gradually shifting the security services from fighting a war back to policing or subjugating the civilian population as well as reining in unruly militias. This will include integrating the disparate paramilitary forces that emerged in the past seven years. His second task is to run the border crossings with Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon as well as to follow up on the Assad regime’s objective of preventing3 the flow of Turkish products into the Syrian market.

Assad’s appointment of a new interior minister will gradually shift the security services from fighting a war back to policing or subjugating the civilian population as well as reining in unruly paramilitary militias.

The second move by the Assad regime was to convert the national reconciliation ministry, led by Ali Haidar (who has strong ties to Moscow), to a commission. The assessment is mixed on what this move might mean. On the one hand Ali Haidar, who is typically outspoken, has been quiet since November 26 and has lost the ministerial privileges that strengthened his portfolio. On the other hand, Haidar will retain this post in the long run and will no longer go through the general secretariat of the government—hence Russian authorities can more easily navigate and directly engage the new national reconciliation commission. While Moscow’s demand to institutionalize the reconciliation process has been met, Haidar’s public profile seems to have been lowered.

The third noteworthy move was the appointment of the young Adel al-Alabi, the vice chair of the board of directors of the Damascus Cham Holding Company, as governor of Damascus province, a key position in the Assad regime bureaucracy. His predecessor, Bishr al-Sabban, served from 2006 until last week and is on the European Union’s sanctions list for “the violent repression against” Syrian civilians. Al-Sabban’s corruption is largely known among Damascenes and he is closely connected to Rami Makhlouf, the maternal cousin of Bashar al-Assad, and to the Iranian regime.

Adel al-Alabi appointment might allow Assad to accelerate the real estate and business projects planned for Damascus and its suburbs, including Marota City and Basilia City, projects that are meant to symbolize the Assad regime’s comeback and solidify the demographic changes in Damascus and its suburbs. Al-Alabi’s appointment and the selection of Hazem Qarfoul last September as governor of the Central Bank of Syria mean that the new figures are expected to facilitate the reconstruction process and consolidate the emergence of a new postwar class of businessmen in the regime’s inner circle.

Regime Difficulties

The Syrian regime is facing challenges in securing the financial resources and military manpower to execute this three-year plan. The 2019 budget passed last week reflects the financial constraints of not having foreign aid. The nearly $8.9 billion allocated for next year indicates a dire forecast for the Syrian economy as the state budget exceeds 50 percent of GDP and totals less than half of the 2011 budget. While the regime promised 69,000 new government jobs, the deficit is at $2.2 billion and reconstruction constitutes only 22 percent of the budget, which is an insignificant amount given that the United Nations estimated the overall price tag of the reconstruction of Syria at $400 billion.

The Syrian regime is facing challenges in securing the financial resources and military manpower to execute its near-term plans. The nearly $8.9 billion budget allocated for next year is less than half that of 2011.

The Syrian army has also been overstretched in the past seven years. Now that the war is winding down, on December 10 the regime ended the active service of conscripted officers who have served five years during the war, far beyond their initial 18-month term of mandatory military service. This move comes despite the Syrian Druze community’s rejection of Assad’s call to serve in the military. Assad’s plan to expand the armed forces largely depends on the ability to secure a sufficient number of conscripts to assert control over recaptured areas, which remains a challenge as the size of the army shrank compared to pre-2011 levels.

Indeed, after controlling over 60 percent of Syrian territory, the Assad regime has until 2021 to reconstruct its power and polish its image, hence there is no external pressure until then to concede some of its powers to the opposition or take measures that might lead to a crack in the regime’s composition. Therefore, the approach in the next three years will be to utilize the new incoming resources in an attempt to strike deals and provide services to tribes in southern, northern, and central Syria so they shift their loyalties back from the United States and Turkey. Above all, these measures by Damascus reflect the growing Russian clout over the Assad regime. While Washington consented to Assad’s remaining in power until 2021, the Trump Administration’s suggestion to pull the plug on the Astana talks, without actively offering a viable alternative, might strengthen Assad’s hand to execute his plan.

1 Source is in Arabic.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.