On January 30, the Southern Resistance Forces (SRF) in Yemen, backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), forcefully seized control of Aden, the interim capital of the Saudi Arabia-backed and internationally recognized Yemeni government. This crucial development will have an immediate impact on the country’s two major wars: the Arab Coalition battle against the Houthis, and the US battle against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). If separatist forces manage to completely subdue the already fragile authority of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, Yemen could regress to the north-south partition of the pre-1990 period. Restoring US diplomacy is paramount to preventing further chaos in the country, a scenario that will aggravate Yemen’s humanitarian crisis and allow AQAP to regain strength in the southern governorates.

The Battle of Aden

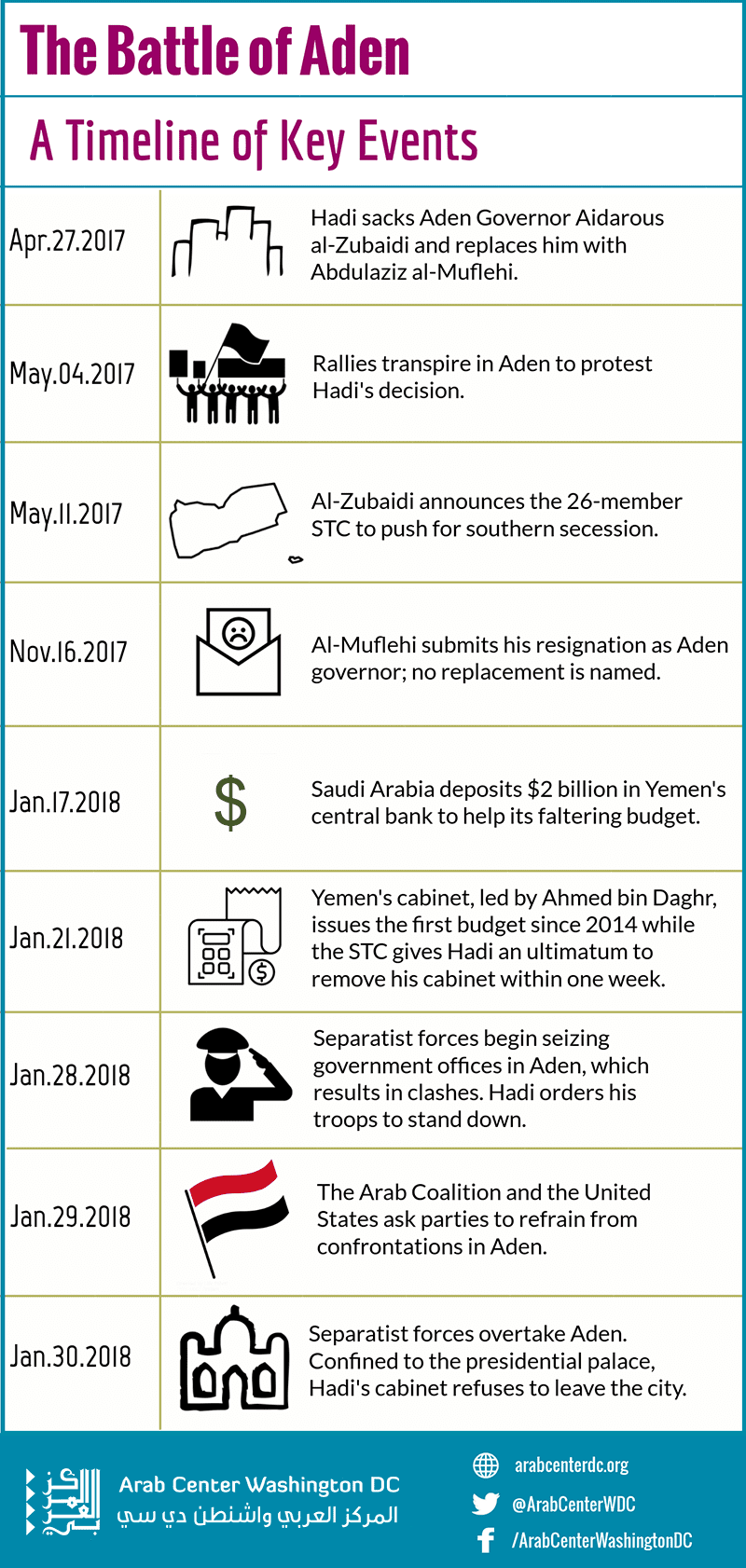

Tensions in Aden have been increasing since last year, as shown in the sequence of events below. Most recently, on January 21, the SRF declared its intention to change Hadi’s government and replace it with a “cabinet of technocrats.” The SRF also announced plans to become the nucleus of a new force that would maintain security in southern Yemen and ban all northern military and security officials from entering, including those loyal to Hadi. The Southern Transitional Council (STC) leader, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, gave President Hadi a one-week deadline to oust the cabinet of Prime Minister Ahmed bin Daghr, a cabinet the STC accused of “corruption and mismanagement.” On January 28—the deadline that was set—Hadi rejected the ultimatum. The separatists then launched their offensive and asserted control over the port city of Aden within two days, as Hadi instructed his forces to “stand down.”

It is not clear yet where things stand in a fluid and rapidly evolving situation. Bin Daghr and his cabinet seem to be on lockdown in the presidential palace in Aden. On February 1, the Arab Coalition issued a statement affirming that “Saudi Arabia and the UAE have no ambitions but for Yemen to be a safe, stable, and able, Arab nation.” The statement urged all parties to focus on “defeating the Houthi militias of Iran”; however, it stopped short of endorsing the Hadi government, which described1 what happened as “a failed coup to disrupt the work of the legitimate government.” Pending questions remain, including: 1) Will the bin Daghr government remain in place and will there be a long political impasse? 2) Will the SRF retain control of key government offices or will they give them back to the Yemen government? 3) What role will Hadi will play moving forward? One thing is clear, though: the STC is now in control of Aden no matter what the outcome will be.

These developments, at face value, should not come as a surprise. Aden has had secessionist inclinations since it was a British colony in the 19th century. The southern movement, or al-Hirak al-Janoubi, has been gradually gaining momentum since its inception in 2007. The takeover of Aden from the Houthis in July 2015 provided an opportunity to translate the movement’s ideas into action. The struggle for power in Sanaa since the 2011 Yemeni uprising helped make the secessionists’ case. However, what is new this time is the deliberate foreign support to organize, expand, and systemize the secession at the expense of a central—albeit dysfunctional—authority.

Is There a Saudi-Emirati Divide in Yemen?

There is an ambiguity regarding where Riyadh and Abu Dhabi stand on developments unfolding in Aden. The two allies share similar objectives in Yemen; however, it has become more challenging to reconcile their interests during the past two years despite denials about their differences. As President Hadi was struggling to lead the military battle against the Houthis, Saudi Arabia was looking for someone with military experience and tribal connections to take the mantle on the ground. Ultimately, in April 2016 Hadi replaced his UAE-supported vice president, Khaled Bahah, with General Mohsen al-Ahmar, the Muslim Brotherhood-inspired Islah Party leader. That move stirred tensions in Aden.

Despite Hadi’s objections while in exile in Riyadh, the UAE extended direct support and funding to the “Security Belt” forces—the southern units, presumably under governmental authority, that are active in Aden, Hadramawt, and Shabwa, among other governorates. Since last year, these forces have been cracking down on Islah Party loyalists in Aden. Following Saudi mediation, the UAE recently appeared to warm up to the idea of dealing with Islah after the party reportedly severed ties with the Muslim Brotherhood, a move welcomed by Abu Dhabi last December as “an opportunity to test their intentions in the interest of Yemen and the Arab region.” However, the decision to forcefully oust the bin Daghr cabinet indicates that this rapprochement fell apart within weeks, most notably after the assassination of Yemen’s former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, last December. Security Belt forces have defied2 Hadi’s instructions and prevented Yemeni citizens fleeing the northern governorates from entering Aden via the Lahij governorate.

The loss of Aden is a blow to the Saudi campaign in Yemen and to Riyadh’s recent attempts to prop up the Hadi government. Saudi Arabia has been focused largely on protecting its southern border from the Houthis’ attacks, while the UAE has been amassing power in Aden in the last two years. The Arab Coalition warned in a statement on January 30 that all necessary measures will be taken “to restore security and stability in Aden,” having met with both bin Daghr and al-Zubaidi to that end. Northern military commanders leading the fight against the Houthis in the western provinces reportedly issued a veiled warning to the Arab Coalition that they are ready to leave the battlefield and head to Aden to clash with the separatists, if the situation is not resolved.

US Silence on Yemen

There are no indications that the United States is willing or planning to intervene politically to resolve the standoff in Aden. The US reaction has been minimal so far, which is forcing the hand of the Hadi government. State Department spokesperson Heather Nauert issued a statement on January 29 asking all parties “to refrain from escalation and further bloodshed” and suggesting that political dialogue is “the only way to achieve a more stable, unified, and prosperous Yemen.” While highlighting the unity of Yemen, the statement did not refer to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the Hadi government, or the separatists. Therefore, it is increasingly obvious that Washington will let things run their course in Aden. The Pentagon has confirmed that the United States has “no plans to curtail support for the coalition partners,” which means it will not leverage military and intelligence support to influence the Arab Coalition’s policies.

Meanwhile, Washington remains focused on fighting terrorism in southern Yemen. Under the Trump Administration, US airstrikes against AQAP have increased sixfold so far, compared to 2016. The effectiveness of that battle has been limited, however, mostly because of a previous US mission that resulted in the death of a US Navy elite soldier in the early days of Trump’s presidency. The United States no longer has special forces on the ground in Yemen to guide operations and it is mostly relying on drone strikes to target AQAP, which remains largely present in the Hadramawt, Bayda, and Shabwa governorates. The Security Belt forces have increased security measures in recent weeks, arguing that AQAP might infiltrate Saleh loyalists who fled the north in large numbers, fearing a Houthi crackdown. The blurred line between AQAP and northern Yemenis could further increase tensions in the south.

The Saudi-backed Hadi government has been making inroads in recent weeks in its military operations against the Houthis, whether in the al-Jawf, Maarib, or Taiz governorates. The separatists might have concerns that these gains could translate into a growing influence by the Islah Party in the Yemeni government. Hadi’s commanders are focused on taking over Sanaa while the separatists want to fill the void they left behind in Aden. The Hadi government, which failed to deliver in Aden, is now caught in the crossfire between the Houthis and the separatists.

The failure to achieve a military victory or resolve Yemen’s war has exacerbated divisions in both the north and the south. The Houthis assassinated former President Ali Abdullah Saleh in December, which led to the fall of the northern coalition. The recent takeover of Aden by the Southern Resistance Forces signals the demise of the anti-Houthi alliance in the south, and this could gradually end any coalition attempt to take control of Sanaa.

The prognosis for Yemen is grim. As separatist forces were giving an ultimatum to the Hadi government to resign, United Nations envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed resigned from his post the next day, on January 22, nearly a month before the end of his three-year mandate. UN Secretary General António Guterres plans to appoint Martin Griffith, a former British diplomat, to replace Cheikh Ahmed.

There is no roadmap for a political process in Yemen. With the death of Saleh, and with Hadi nearly finished politically, the negotiations could now be confined to the two most potent armed groups: the separatists and the Houthis.

Further, the fact is that the Arab Coalition is no longer cohesive. There is a soft proxy war now between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in Yemen. Hadi has mostly kept a low profile in the past few months, as the two Gulf partners were trying to reach common ground on the best way forward in Aden. Unconfirmed chatter3 in Yemen’s media indicates that the Arab Coalition agreed on delegating security control to the separatist forces and upgrading the status of the STC as a major player in the southern governorates. The bottom line is that at this point, Riyadh sees floating the idea of secession as one that would undermine the war effort against the Houthis, while the UAE believes that the Islah Party should be disempowered.

History shows that neither unification nor division have helped reconcile the deep political differences in southern Yemen. The idea that dividing Yemen would resolve all the problems and provide an exit from the country’s quagmire is shortsighted. Reverting to the UN-sponsored political process remains the only viable option for Yemen, and the United States should make it a priority to pressure all parties involved to work toward that goal.

1 Source is in Arabic.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.