For years now, the United States has been grappling with its global leadership role in the face of military commitments, mounting expenses, and ambivalent strategic concepts. President Barack Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” gave way to President Donald Trump’s push to end “forever wars” in the region. Both policies bewildered and alarmed US allies worldwide, leading not so much to real change as to more of the same policies but under different slogans. This has created confusion in US policy in the Middle East and elsewhere and led to mounting challenges to the American position overseas.

As the United States has wrestled with its global role, and particularly in the Middle East, others have sought to take advantage of the unstable situation. Russia, for example, has acted opportunistically to advance its own interests at the expense of the United States. Moscow has leveraged its intervention in Syria to expand its military presence in that country and its role in the eastern Mediterranean while expanding diplomatic relations and military ties with a number of US partners. Although this development should be of concern to American policy-makers, Russian gains have been broad but relatively shallow. The United States remains the key external arbiter in the region.

But there is another superpower on the horizon that appears to be eyeing the Middle East and the potential advantages presented by the apparent deterioration of the US position: China. With extensive interests in the region, Beijing is considering its options in an environment characterized by deteriorating relations with the United States and the upheaval of international politics brought about by the coronavirus.

With extensive interests in the region, Beijing is considering its options in an environment characterized by deteriorating relations with the United States.

China has certain advantages to press: its emphasis on economic ties and downplaying of human rights concerns appeals strongly to most countries of the Middle East, offering a welcome alternative to American supremacy and Russian scheming, with few strings attached. China’s foreign policy approach has thus allowed it to take advantage of chaos on the international stage and the confusion and instability of American foreign policy to quietly advance its interests in the region. Beijing has something of an edge here: it is not necessarily seen as a potential hegemon, as the United States sometimes is perceived, nor as a former empire trying to recapture lost glory, as is the case with Russia. China thus has a niche advantage in the region at the moment, if it cares to exploit it.

The New Silk Road: Basis of Chinese Policy

Over the past several years, China has focused extensively on building trade and economic ties with the Middle East, motivated by profit, diplomacy, and necessity. In 2015 China became the world’s leading importer of crude oil, with the Middle East accounting for half its total imports. As of 2016 China assumed the role of top foreign investor in the region, having pledged $29.7 billion in new investment there (compared to $7 billion by the United States). Beijing is now the region’s largest investor, committing tens of billions of dollars in reconstruction, banking sector, and other commercial loans to the region. Trade relations have gown to around $245 billion.

China’s vast Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), announced by President Xi Jinping in 2013, aims to incorporate the Middle East region into Beijing’s broader ambitions. Now enshrined in its constitution as the cornerstone of China’s geopolitical ambitions, the BRI has prioritized the region due to its economic importance and significance as a trade and communications route. Since 2013, China has invested more than $123 billion in BRI-related projects in the region, and in 2016 it became the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Middle East, a total that has increased substantially since then. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, Djibouti, and Egypt have all been announced as the sites of major Chinese port and infrastructure development. Several countries have aligned their (admittedly small) sustainable economy initiatives with the Chinese government, in a step intended to integrate their economies more fully into Chinese regional plans. And on the digital front, a major stage of the digital economy’s advancement, China has 5G agreements with each of the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council. While other Arab states have had differing degrees of openness to China, certain others remain marginalized, including Yemen, Palestine, and Lebanon, but are viewed as ripe for partnership approaches.

Active Diplomacy and Arms Sales

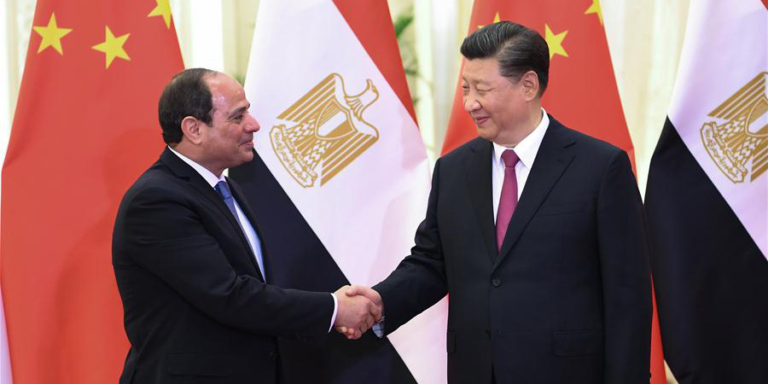

Thus, it is no coincidence that diplomatic and political relations between China and the countries of the region have been growing. President Ji Xinping visited the region twice, in 2016 and 2018, and several Middle Eastern leaders have paid visits to Beijing (in the case of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, around half a dozen times), typically signing a raft of economic and trade agreements while they are in town. China—which eschews American-style alliances, including firm defense commitments—has instead pursued “strategic partnerships” with key countries in the region. Beijing now has various forms of such partnership with every country on the Gulf littoral as well as Djibouti and Egypt. These arrangements are intended to reflect China’s long-term interest in regional stability, productive economic and diplomatic relationships, and, significantly, desire to counterbalance US influence.

These arrangements are intended to reflect China’s long-term interest in regional stability, productive economic and diplomatic relationships, and, significantly, desire to counterbalance US influence.

To complement this approach, Beijing has taken limited steps to expand its military involvement in the region. China has participated in anti-piracy initiatives off the Horn of Africa and, in 2017, opened a small naval base in Djibouti. Additional such facilities may be constructed as the BRI expands and Chinese interests find themselves in need of protection.

Hand in hand with its small but strategic military presence, China has increased arms sales to key regional countries. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have purchased relatively small amounts of arms from Beijing—about $40 million each in 2018—and the UAE has plans for joint development of weapons with China. (Saudi Arabia purchased a Chinese missile system in 2007, apparently with the approval of the George W. Bush Administration.) The deals, while minor compared to the tens of billions of dollars in US arms sales to the region, have cracked open a door to the lucrative Gulf market and are likely to expand in coming years. As with diplomatic and economic ties, arms sales from China come with few strings attached, whether related to human rights, non-proliferation, or the sort of legal requirements in US law concerning regional arms sales designed to ensure the maintenance of Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge.

COVID-19 Diplomacy: Another Front, and It’s Working

Despite the uproar (loudly led by, but by no means limited to, the United States) over China’s role in the origins and initial spread of Sars-Cov-2, the Chinese government has adroitly capitalized on the crisis to enhance its own brand in the Middle East. A recipient of aid from the Middle East in the early days of the outbreak—however symbolic—China soon reversed the flow, pushing material and technical aid to Middle East states in significant volume. The effort was accompanied by a major cultural and information campaign to create a sense of solidarity between China and key regional countries, particularly in the Gulf. Egypt, too, was a recipient of Chinese political attention as Beijing tried to build its image as a concerned benefactor in the viral crisis.

It remains to be seen whether China’s opportunistic COVID-19 diplomacy will make long-term inroads into the hearts and minds—and, most important, the politics and diplomatic affinities—of the Gulf and the broader Middle East. But it demonstrates the Chinese determination to capitalize on opportunities in accordance with a well-conceptualized framework of foreign relations and superpower politics.

China and the Future of Regional Security

With China positioning itself to expand and defend its interests in the Middle East, the question is whether Beijing aims to compete with or replace the United States as an external political arbiter and guarantor of security.

The Trump Administration has sent mixed signals. In June 2019, Trump tweeted that China (as well as Japan and “many other countries,” as major consumers of Middle East oil) should be “protecting their own ships … We don’t even need to be there.” To be sure, China’s stated reliance on a US security blanket that guarantees the dependable free flow of oil is a source of some worry in Beijing, particularly as tensions with the United States deepen. And should the geopolitics trend in the opposite direction—and the United States truly embark on a major reduction of its security commitments in the region, especially in the Gulf—Beijing would be under pressure to fulfill its obligations there in order to safeguard its own economic interests, if not to assume the role as a presumed superpower.

China has the naval assets and experience to handle a role in securing sea lanes in the Gulf and northern Arabian Sea.

Certainly, China has the naval assets and experience to handle a role in securing sea lanes in the Gulf and northern Arabian Sea. The US Office of Naval Intelligence has estimated that by the end of 2020, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (or PLAN, as the Chinese navy is formally known) will have a heavily modernized fleet of 360 battle force ships, compared with an estimated 297 for the United States. China is also developing naval access in the Middle East and South Asia; in addition to its naval facility in Djibouti, China is managing and developing the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, and in the future may be able to mount operations out of Duqm, Oman, under development as part of the BRI. It has not gone unnoticed in the Pentagon that Beijing has taken over management of Israel’s Haifa port, a major stop for the US Sixth Fleet, on a 25-year lease. China also has agreements with several countries to provide “technical service stops” for its naval elements.

The relationship with Israel, however, is raising concerns in Washington. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s last visit to Israel included frank discussions about American requests that Israel curb its economic relations with China, specifically those relating to its security. There also are American concerns about China’s involvement in building an Israeli desalination plant near a nuclear center and an airbase and its efforts to engage Israel in its 5G communication networks.

The PLAN has also developed considerable experience in regional security operations based on over ten years of participation in anti-piracy activities in the Gulf of Aden as well as contributing small numbers of troops to various peacekeeping operations. Last year, China briefly considered, then backed away from, taking part in the US-led Gulf maritime security exercise, Operation Sentinel. It does not, however, have a record of managing Gulf naval operations under hostile fire, as the United States does from its experiences in both Gulf wars, the so-called “tanker war” of the 1980s, and other incidents over the last three decades. This will surely have an impact on China’s thinking about the potential for more extensive involvement in Gulf security operations in the future.

At present, a greater Chinese role in other regional security or diplomacy efforts does not appear to be in the cards. For one thing, China’s approach to global engagement, while firmly predicated on maintaining its continuing rise as a global superpower, still prizes the general concept of non-alignment, which translates into the avoidance of entangling alliances, difficult and controversial diplomatic initiatives, and large-scale overseas military deployments. China also values non-interference in the internal affairs of others (at least when it comes to pushing human rights concerns on its partners or responding to similar concerns that outside powers press upon it). As a result, Chinese diplomacy in the region has largely tried to steer a middle course between competing powers there, thus maintaining good relations with Iran and Israel while avoiding running afoul of American and Arab states’ sensibilities.

Taking a more active role in Gulf security could potentially insert China into the middle of tensions between the Gulf Arab states and Iran, China’s main regional trading partner, source of oil, and recipient of FDI.

In addition, Beijing reckons that the regional security architecture, and in particular the US-led maritime security regime in the Gulf, is of enormous benefit to Chinese interests, protecting lines of communication, transportation, and commerce at very little cost to China itself. Seeking to replace the United States in this role, or even attempting to play a significantly larger role in Gulf maritime security, could prove expensive for the Chinese government and a painful stretch for the PLAN’s existing capabilities. Moreover, taking a more active role in Gulf security could potentially insert China into the middle of tensions between the Gulf Arab states and Iran, China’s main regional trading partner, source of oil, and recipient of FDI; this would create an uncomfortable and risky position for Chinese diplomacy and interests. At the moment, then, China appears content with the status quo.

If Things Go from Bad to Worse…

A number of factors could affect this calculus. The increasing tensions between the United States and China over the coronavirus, Hong Kong, and trade point to a growing risk of diplomatic confrontation that could play out in unpredictable ways, particularly given the Trump Administration’s erratic foreign policy and American election year politics. Beijing might be tempted to take a page from the Russian playbook and seek to make political inroads in the region to push back against Washington.

For the longer term, China might reconsider its national security approach. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi recently warned that a new cold war with the United States may be on the horizon. Were this to become more reality than rhetoric, in the Middle East region it could take the form of increased Chinese efforts to expand its security role through increased arms sales and access agreements, as well as stepped-up efforts to advance economic ties. All this might be accompanied by information campaigns to valorize Chinese cultural and political ties with countries of the region, while hinting at US unreliability as an ally. China’s coronavirus diplomacy demonstrates how such efforts could reap easy dividends while drawing unflattering (if unspoken) comparisons to the United States.

While replacing the United States appears neither desirable (from Beijing’s point of view) nor practical in the short-to-medium term, China is reasonably well positioned to be more of a force to be reckoned with in the region. By opportunistically capitalizing on Washington’s mistakes, Moscow has done just that, and Beijing might take a lesson from its experience. If a new cold war pitting China against the United States is coming, the Middle East is poised to become a prime venue.