Four months after Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri was designated to lead a national unity government on May 24, there appears to be no end in sight for the process of forming the next cabinet. There are several internal and external factors behind a stalemate that seems to be a blessing in disguise because it is delaying a looming political confrontation between the country’s ruling elites about several domestic and regional issues.

Typically, the stalemate reflects the political dynamics of the ruling elites as well as the influential powers in Lebanese politics.

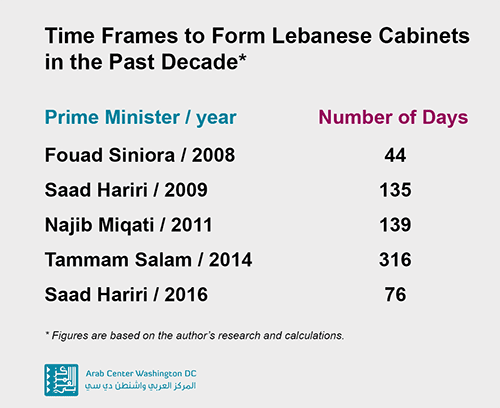

Eighteen days after his weak performance in the May 6 parliamentary elections, a prevailing legislative majority (111 out of 118 deputies) named Hariri as their choice for future prime minister during consultations with President Michel Aoun. But on September 3, Aoun declined to endorse a draft cabinet Hariri officially presented to him, which further cemented the political stalemate. The expectation last May was that the cabinet would be created swiftly; however, the long period for forming the government has been a feature of Lebanese politics in the past decade (see table below). Typically, the stalemate reflects the political dynamics of the ruling elites as well as the influential powers in Lebanese politics. This paper will identify two internal and two external factors that are delaying the formation of the Lebanese cabinet in 2018.

Internal Factors

1. The evolving Aoun-Hariri relationship. The first expectation was that the pre-election synergy between Aoun and Hariri would continue past the 2018 elections, most notably after the president’s role in helping secure Hariri’s release during his detention in Saudi Arabia in November 2017. However, this was not the case. On September 11, Aoun was quoted1 as saying that Hariri had changed considerably since the 2016 presidential deal, in reference to when the prime minister made a significant shift by endorsing his arch political rival Aoun for the presidency.

Yet, there have been several indications that Hariri could do a political U-turn and, once again, become more aligned with Saudi policy. On May 12, his chief of staff (and cousin) Nader Hariri submitted his resignation, ostensibly at the prime minister’s request. Nader Hariri had orchestrated the 2016 presidential deal along with Aoun’s son-in-law and foreign minister Gebran Bassil. Saad Hariri was not merely reshuffling his own team but also reconsidering his political alliances. He has long been criticized by the hawks in the Future Movement that he leads, and by Saudi Arabia, as being too soft in dealing with Aoun since returning to the premiership in December 2016. The two leaders have differed recently on the constitutional rights of the Maronite president and the Sunni prime minister in the government formation process, and this helped Hariri shore up his popularity among his Sunni base.

Hariri travelled to The Hague this month to observe the closing arguments in the case of the February 2005 assassination of his father, former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. Four Hezbollah members are being tried in absentia for allegedly planning and executing the bombing in Beirut that killed him. The Lebanese premier noted that “we have always wanted justice and have not resorted to revenge.” Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah warned about linking the government formation to the Hariri trial, saying “the tribunal does not exist, and its decisions do not concern us at all, do not play with fire.” While these court deliberations did not impact Lebanese politics in recent months, political tensions can potentially intensify between the Future Movement and Hezbollah if the charges by the UN-backed tribunal are confirmed. Such an outcome might further complicate the relations between President Aoun, Hezbollah’s long-time ally, and the prime minister.

How Aoun and Hariri will manage the dynamics of the executive branch moving forward will be a key factor in Lebanese politics.

In the short term, Aoun and Hariri will at least maintain their cordial relationship since they both need each other to remain effective in governing. However, the new rules of engagement between them might gradually break their brief political alliance, which arguably was the main factor in their performance in the last parliamentary elections. How Aoun and Hariri will manage the dynamics of the executive branch moving forward will be a key factor in Lebanese politics.

2. Sectarian factors: Christian and Druze representation. The sectarian quota is at the core of cabinet representation in Lebanon. The government is meant to reflect the power distribution of parliamentary elections; however, interpretation of these results is subjective. One of the major domestic barriers to the cabinet formation has been deciding how to share the Christian quota (14 seats) between the two main Christian leaders, President Aoun and Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea. Since 2016, Aoun has agreed with Hariri that there would be a quota for the president in addition to that of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM). The Lebanese president has been elected as an independent since the 1990s, hence Aoun’s election in 2016 posed a challenge to the rule of allocating a quota to the president since he already leads a major political party.

The second challenge to forming the cabinet has been Druze representation. Aoun wants to keep a ministerial position for Druze leader Talal Arslan, a loyal ally of the president; this was the case in the cabinet installed in 2016 when Arslan was on good terms with Walid Joumblatt, the long-serving Druze chief. However, tensions have grown between Joumblatt and Arslan since last May when the latter aligned himself with FPM in the parliamentary elections. Joumblatt wants to reclaim all three seats allocated for the Druze quota, while Aoun is concerned that the veteran Druze leader could disrupt the government. If Joumblatt decides to submit the resignation of his three potential Druze ministers, the government could lose its national appeal as it no longer would represent all confessional communities—hence it could potentially become paralyzed.

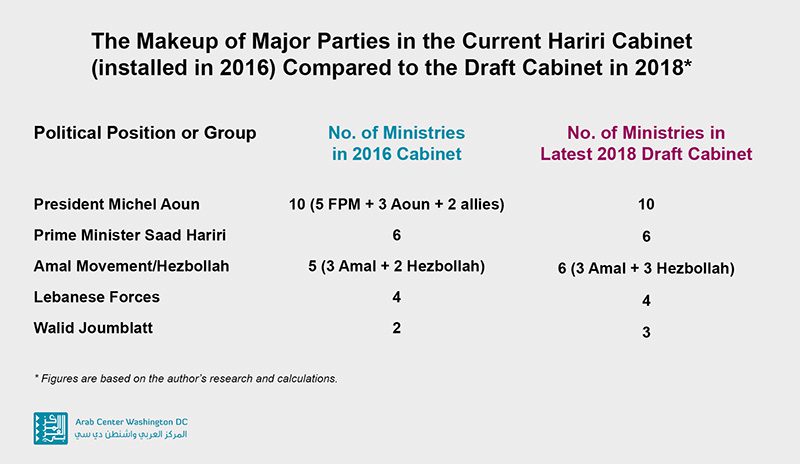

The table above indicates that the quota representation in the latest draft cabinet presented by Hariri nearly matches the current caretaker cabinet. The principal political leaders have settled on keeping the same distribution of what is known as the “sovereign ministries”: foreign, interior, finance, and defense. The only major difference is that Hezbollah was given one additional key ministry (health), instead of two state ministers without portfolio. Aoun had reservations about giving the Lebanese Forces the ministry of justice and denying Arslan a ministerial position. Moving forward, the concerned parties might once again raise their bar for negotiation.

While Hezbollah mostly remains neutral in these backdoor cabinet negotiations, on September 2 the Shia party’s deputy secretary general, Naim Qassem, issued a statement that was interpreted as a rebuke to Gebran Bassil’s presidential ambitions: “He who believes that his position in the government prepares him to be president of the republic … is deceived.” Geagea responded with a soft approach, mildly admonishing Hezbollah in his latest speech on September 9 by saying, “Come back to Lebanon [from Syria] and we will be waiting for you,” hinting that if the party ends its military intervention in Syria he will be ready to engage Hezbollah politically.

The post elections calculations are different for the Lebanese ruling elites. Now that he is president, Aoun no longer receives Hezbollah’s support in his negotiations with Hariri to form the cabinet, as was the case before 2016. In return, the prime minister is unable to disregard the negotiation demands of Geagea and Joumblatt, since he might be criticized by Saudi officials for appeasing Aoun.

External Factors

1. The Syrian regime dilemma: To engage or not to engage. There is increasing political pressure on Hariri to engage the Syrian regime on two major issues that are vital for Lebanon: the return of Syrian refugees and the opening of the Nasib border crossing between Syria and Jordan, which is vital for Lebanese exports to the Gulf. The Shia alliance, Hezbollah, and the Amal Movement, President Aoun and the Free Patriotic Movement, as well as Christian and Sunni leaders allied with the Syrian regime are all demanding some sort of engagement with Damascus. In return, Hariri, Joumblatt, and Geagea are reluctant to engage before there is a resolution to the conflict in Syria. This political divide echoes the rivalry between the March 14 and March 8 alliances and reflects where things stand in the Syrian war at this point.

It will be difficult for Hariri to engage the Syrian regime without a nod from the United States and Saudi Arabia, while Hezbollah is aligned with Iranian and Russian views of normalizing relations between the regime and its Arab neighbors.

On August 15, Hariri announced that engaging the Syrian regime is “not up for discussion” while Nasrallah responded by advising2 “political leaders”––meaning Hariri without naming him—“not to commit to positions they might backtrack on” later. It will be difficult for Hariri to engage the Syrian regime without a nod from the United States and Saudi Arabia, while Hezbollah is aligned with Iranian and Russian views of normalizing relations between the regime and its Arab neighbors. Although this issue is not currently dominant in the political discourse, Lebanese leaders will have to face it at some point, which might lead to political tensions, measured engagement, or maintenance of the status quo. The director of the General Directorate of General Security, Abbas Ibrahim, remains for now the point person representing the president in dealing with the Syrian regime.

2. The Trump factor: US-Iranian tensions. On May 8, two days after the Lebanese parliamentary elections, President Donald Trump announced the withdrawal of the United States from the Iran nuclear deal. This may have had some impact on the government formation process in Lebanon. The lack of clarity on whether the Trump Administration is indeed preparing a plan to deter Iran’s regional influence is driving some Lebanese politicians to hedge their bets with a wait-and-see approach. If either Washington or Tehran initiate a direct move to deter each other, this will be felt immediately in Lebanon as the two countries are arguably the most decisive external players in Lebanese politics. However, there are no indications that either the United States or Iran want to go down this road, one that might endanger their leverage in Lebanon. US officials were allegedly quoted as saying that the Trump Administration refused any qualitative or quantitative increase in Hezbollah’s share in the Lebanese cabinet, including the health ministry. If true, the United States might play a disruptive role in the cabinet formation process.

What to Expect, and US Options

While there is clearly a good deal of confessional squabbling in the cabinet formation process, external pressure can seal the deal in forming a unity government since the gap in the negotiations is narrow. Hezbollah is not throwing its weight in the process and Hariri does not seem to be in a rush to end the stalemate. Ultimately, the Lebanese cabinet is likely to be formed within the set criteria of the current cabinet, and the pending details will be sorted out one way or another. The only positive aspect of the stalemate is that it is delaying a potential confrontation on critical issues that the ruling elite will have to face sooner or later.

However, if the Trump Administration opts to veto giving Hezbollah the health ministry, this would change the dynamics of the cabinet formation and perhaps weaken Hariri’s hand. Most importantly, it would shift the focus from domestic politics to a narrative about US intervention in Lebanese affairs.

US pressure on Hezbollah could be more effective using other means of leverage. The stalemate in Lebanon cannot and should not last long. The economic situation is dire, and the public debt has reached $83 billion. Iran and the United States would do well to convince their allies to reach a cabinet compromise that is accepted by major parties, one whose members agree on a measured engagement with Damascus on limited issues of interest for Lebanon without bypassing the prime minister. Hariri is in a strong position to form the cabinet, but his options are limited, and he no longer holds the same large parliamentary bloc he had before 2018. Given the ambiguous regional context, maintaining the status quo in Lebanon under a national unity government appears to be the best option for all parties concerned.