It is difficult to make Iran’s theocratic leaders appear to be the less belligerent party of a nasty diplomatic confrontation, but President Donald Trump seems to have done just that with his all-caps rant at the Iranian regime on July 22, threatening dire circumstances (“…YOU WILL SUFFER CONSEQUENCES THE LIKES OF WHICH FEW THROUGHOUT HISTORY HAVE EVER SUFFERED BEFORE”). His tweet was a reaction to relatively less menacing—by Iranian standards—observations by President Hassan Rouhani that Tehran might react to US pressure on its oil exports by closing the Strait of Hormuz, and that a US attack on Iran would turn out to be the “mother of all wars.”

In response, Mohammed Javad Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister, tweeted back a few hours later: “COLOR US UNIMPRESSED: The world heard even harsher bluster a few months ago. And Iranians have heard them —albeit more civilized ones—for 40 yrs…BE CAUTIOUS!” The next day, an Iranian Foreign Ministry statement added that “If America wants to take a serious step in this direction it will definitely be met with a reaction and equal countermeasures from Iran.” Rouhani himself then appeared to put an end to the tit-for-tat by remarking that he did not think it necessary to respond to every tweet from the American president.

The twists and turns surrounding US-Iran relations over the last couple of weeks suggest a degree of policy confusion that is not rare for this administration.

Shortly thereafter, Trump seemed to alter course and expressed willingness to negotiate with Iran. In a speech on July 24 to the national convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the president proclaimed that “Iran is not the same country anymore” because of US pressure, “and we’ll see what happens, but we’re ready to make a real deal, not the [nuclear] deal that was done by the previous administration, which was a disaster.” Then on July 30, he went all out and announced that he would be willing to negotiate with Iran’s leaders without preconditions.

From threats of war to offers of negotiation in a span of about ten days—evidently this is business as usual for the Trump White House—these events also represented a serious escalation in tensions between the United States and Iran. The US president’s unpredictability—on which he prides himself—made the situation all the more dangerous. Even more troubling, the episode revealed a lack of a coherent Iran policy in the wake of the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) regulating Iran’s nuclear program. The risk of an unintended US-Iran confrontation may be rising.

Tougher Toward Tehran

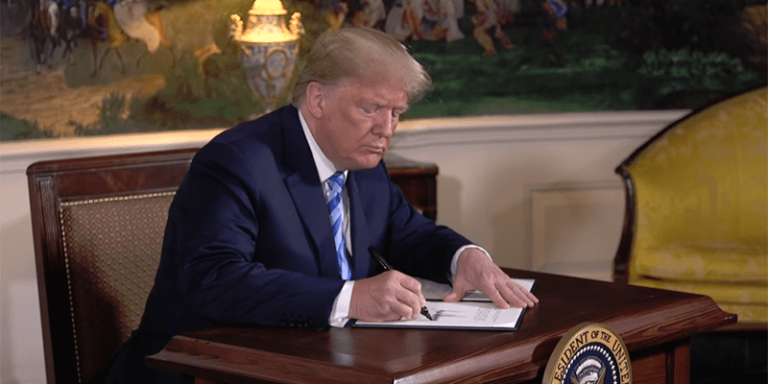

President Trump has a well-established record of antipathy to the Iranian regime and to the nuclear deal President Barack Obama signed in 2015 at the successful conclusion of negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 countries. However, while denigrating the deal and pledging to tighten the screws on Iran, the Trump Administration nevertheless continued to waive sanctions and certify Iran’s compliance with the terms of the JCPOA until October 2017, when Trump decertified the deal while remaining within it. The administration’s formal withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018, accompanied by the reimposition of US sanctions that had been suspended pursuant to the terms of the JCPOA, marked a new phase in official American hostility toward Iran.

There are three possible American policies toward Iran: increased pressure, regime change, and sudden direct negotiations.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, a known Iran hawk himself, laid out the American approach in a speech to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library on July 22, delivered shortly before Trump’s “consequences” tweet the same day. Pompeo assailed the clerical regime’s entrenched corruption and massive human rights violations, pledging a “diplomatic and financial pressure campaign to cut off the funds that the regime uses to enrich itself,” undertake foreign adventurism, and support terrorism. The campaign is centered on the “reimposition of sanctions on Iran’s banking and energy sectors.” (The United States has demanded that major allies curb oil imports from Iran by November 4, a demand the administration has since softened. It has also threatened secondary sanctions on companies that continue to do business in Iran.) Pompeo added that the United States will launch a “new 24/7 Farsi-language TV channel” including “radio, digital, and social media” platforms to influence Iranians at home and abroad. He affirmed that Trump would be willing to talk to the Iranian leadership—but only if there are “irreversible changes in the Iranian regime” first.

One Iran Policy—Or Three?

The twists and turns surrounding US-Iran relations over the last couple of weeks suggest a degree of policy confusion that is not rare for this administration. On the surface, Trump officials and foreign policy experts agree that there is a relatively coherent overarching approach—escalating pressure on Iran through sanctions to force changes in its destabilizing behavior. Beyond that, however, very little appears to be settled. It seems there are in fact at least three Iran policies vying for supremacy behind the administration’s facade of unity.

The first is the administration’s stated policy, a campaign of relentlessly coordinated pressure on a variety of fronts to force substantial retrenchment in Iran’s international and domestic behavior. The Pompeo speech was clear and convincing in this regard. However, both the Bush 43 and Obama Administrations also applied pressure to varying degrees, with limited success; Pompeo has not made clear just how the Trump Administration’s current efforts would differ in substance from US policy pre-JCPOA. Nor has Pompeo or other senior officials specified how the new policy would bring about the sweeping changes the administration hopes for in a regime that has weathered war, isolation, diplomatic opprobrium, and crippling sanctions for decades while continuing to pursue its own ends. If, as appears to be the case, the administration has concluded that the regime is in enough trouble with its own citizens so that a hard shove from the United States could force it to make major changes, Trump and his team may be in for a disappointment.

That suggests a second possible policy lurking in the wings: regime change. On July 27, Secretary of Defense James Mattis flatly denied that causing the downfall of the clerics in Iran was on the US agenda; rather, he said the goal remains solely to change regime behavior. Likewise, Pompeo has steadfastly refused to utter the words “regime change” (while never specifically ruling out such a goal), but his implication has been that it would take something just that drastic to lead to an improvement in US-Iranian relations. In a speech Pompeo delivered to the Heritage Foundation on May 21, he listed 12 demands of the Iranian government, which, taken together, require Iran to abandon its revolutionary foreign policy and thus the regime’s raison d’être—which is basically regime change by another name. If that is the policy he wishes to advocate, Pompeo would find a willing ally in National Security Advisor John Bolton, who backed regime change in Iran in the past before assuming his present position.

Despite widespread media speculation, at this time US policy does not include plans for imminent military action against Iran.

And there is a third possibility, too: a “bolt from the blue” dealt by the president himself. In a joint press conference with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conti nearly a week after Trump’s fiery tweet at Rouhani, the president reiterated his offer to meet Iranian leaders without preconditions, insisting that “they want to meet, I’ll meet. Anytime they want.” The Iranians promptly rejected the offer on the grounds that the United States has proved “totally unreliable,” but the intriguing possibility exists that Trump might be tempted to launch direct talks, as he did with North Korea, in a similar attempt pull off a “deal” simply because no president has done so since the revolution. But as the United States reimposed sanctions on the Islamic Republic on August 6, Iranian President Rouhani was forthcoming with his country’s readiness to talk, also without preconditions. In other words, the possibility, no matter how remote, remains real.

Questions for the Administration

Which of these approaches will win out in the constant internecine warfare that passes for the policy process in Washington today? The administration seems to be trying to sort it all out. Following Trump’s twitter outburst, Bolton called a rare meeting of the senior-level Principals Committee of the National Security Council to determine, in effect, what US policy toward Iran actually is. Despite widespread media speculation, at this time the policy does not include plans for imminent military action. But quite a few vital questions remain:

- Which of the various demands the administration has levied on Iran are essential to an improvement in relations and which are mere talking points? In this regard, how does the administration measure the success of its policy?

- If the White House correctly supposes that pressure on Iran is working, and if intensified, such pressure would lead to regime collapse, how does the United States plan to deal with the aftermath?

- If the strategy to curb malign Iranian activities fails, is a more active strategy to bring about regime change likely?

- How would the United States plan to engage allies in any military options to deal with Tehran’s destabilizing behavior?

- US participation in the JCPOA has ended, but without a considered alternative. What—aside from tightened sanctions or war—could plausibly ensure that Iran’s nuclear program will remain frozen?

- To what extent is Washington willing to provoke a crisis with European and other allies by imposing secondary sanctions on countries that continue to do business with Tehran? Will such a hardline policy help or hurt efforts to restrain Iran’s nuclear ambitions?

- No agreement was announced at the Helsinki summit between President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin regarding Russian cooperation to circumscribe Iran’s involvement in Syria and its threatening actions elsewhere in the region. (The subject was raised, and the two presidents may have come to an understanding between them, but no one seems to know for certain.) How does cooperation with Russia—or, more likely, continued conflict with Russia—affect the US Iran strategy?

- If the president determines to engage Iran directly, what will he put on the table in any discussions—renewed diplomatic relations? An end to sanctions? More threats? And what will happen if such strategies fail?

It is unlikely the Principals Committee was able to resolve any of these major issues, which are key to the success or failure of American efforts, but one hopes they were at least addressed. One thing, however, appears certain: policy confusion and behind-the-scenes disagreements (fueled from time to time by new presidential outbursts) will continue, making mistakes and miscalculations more likely by both the United States and Iran.

Potential Fallout

Such scenarios could have dangerous consequences. With the level of mutual trust between Iran and the United States at approximately zero, threats and counter-threats can rapidly assume a life of their own. While neither side appears to be threatening military action at this point, a rapid escalation toward conflict could easily occur, especially as sanctions inflict hardship and tensions rise.

A rapid escalation leading to a US-Iranian military clash would endanger military and civilian industrial installations on the Arab side of the Gulf.

The implications for the Arab Gulf states are considerable. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, in particular, are staunch foes of Iran and welcomed Trump’s pressure campaign; others, such as Qatar and Oman, maintain practical if cautious relations with Tehran. But a rapid escalation leading to a US-Iranian military clash would endanger everyone’s interests, not only jeopardizing petroleum exports and other critical shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, but possibly putting military and civilian industrial installations on the Arab side of the Gulf at risk from Iranian missile strikes. Tehran maintains extensive capabilities to disrupt Gulf stability in other ways as well, including by means of terrorism and leveraging ties with its Shia coreligionists in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. For these reasons, the Arab Gulf states should be worried about the possible consequences of Washington’s present course, and especially of aligning themselves with or enabling the Trump Administration’s increasing bellicosity toward Iran.

Similar considerations come into play for the United States. Any miscalculation that sets off an expanded conflict could engage US forces across a very broad front, from launching asset-intensive efforts to reopen the Strait and defend international shipping to protecting Arab Gulf allies on land and sea. US forces in Iraq and Syria could find themselves threatened by Iranian proxies and forces, and anti-American terrorism inspired or directed by Iran could strike over a broader front still. Such scenarios promise debilitating, long-term hostilities with concomitant stresses on US regional forces, even if—or especially if—the United States were to decide on a much wider military engagement with Iran to destroy its military and nuclear infrastructure, and possibly bring about regime change.

The current United States policy of confronting malign Iranian activities in the region, including its appalling human rights record, is in some sense long overdue. The Obama Administration eschewed such an objective primarily due to its desire to pursue the nuclear deal as well as its distaste for hard-nosed engagement in the region and a weary ambition to turn its attention elsewhere (which achieved full expression in Obama’s questionable “pivot to Asia”). However, the Trump Administration’s failure to develop a consistent, comprehensive, and long-term strategy, despite the facade of unity among policy-makers, threatens to undermine its approach and create new threats to regional stability and American interests.