Instead of making the necessary progress to a political solution, as was called for by United Nations Security Council resolution 2414 in 2018, the 43-year-old Western Sahara conflict has triggered some unforeseen escalation on the western side of the Arab world. After the deployment since 1991 of the UN-mandated peacekeeping forces, MINURSO, the conflict shifted from a contained North African dispute between Morocco, the Polisario Front, and Algeria into a wide array of diplomatic tensions that reached places as far away as Iran, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

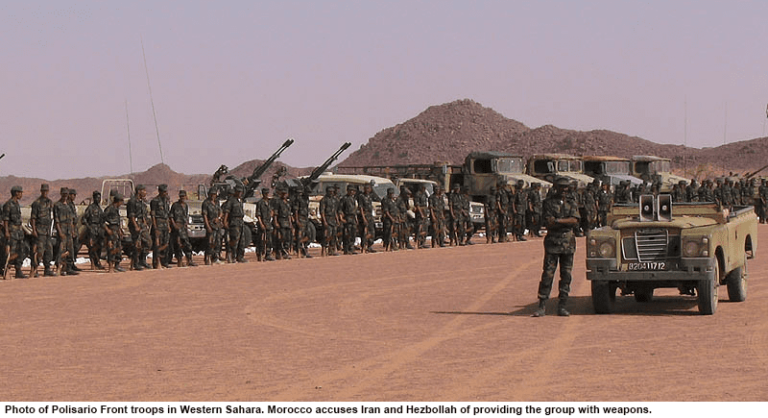

On May 1, Morocco’s Foreign Affairs Minister Nasser Bourita delivered a so-called “secret dossier” to his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javad Zarif, who was “in shock” during their meeting in Tehran. The dossier revealed Iranian-mediated meetings between top Lebanese Shia Hezbollah officials and Polisario representatives in Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria. What was more alarming was the claim that caches of weapons, including truck-mounted anti-aircraft missiles, were smuggled by Hezbollah via Iran’s embassy in neighboring Algeria. Morocco also claimed Hezbollah had initiated the provision of training and financial support to the Polisario in 2016. Bourita maintained his country had “verified proof” of the party’s role and showed Zarif “dates, locations of meetings and the names involved.” This new Lebanese twist and the alleged Hezbollah conspiracy against Morocco’s main concern over its contested sovereignty in the Sahara have sent shockwaves to several regional and western capitals. In short, Morocco’s capital Rabat was left without a choice “but to act and cut diplomatic ties and close its embassy in Tehran.”

Morocco’s problems in its relations with Iran go back to 1979 when Rabat hosted the Shah after his ouster.

However, the timing of Morocco’s decision to sever relations with Iran and to close the Iranian embassy in Rabat “immediately” on May 1, 2018, has raised questions about the real motives of Rabat’s announcement. It came a few days before President Donald Trump’s decision to exit the Iran nuclear deal, amid growing concern among most Gulf states about Iran’s strategy and deepening influence in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen. One day earlier, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had made his theatrical presentation about the alleged Iranian “secret files” as part of his campaign to neutralize the European efforts of French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and British Prime Minister Theresa May to persuade Trump not to exit the nuclear deal.

A Web of Salient Political Vendettas

Morocco’s decision to cut relations with Iran follows a pattern of highs and lows in a rocky relationship with the Islamic Republic since 1979. Ayatollah Khomeini’s government decided to recognize the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in 1980 in a retaliatory move against King Hassan II’s decision to host Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in exile after the fall of his regime. Relations between the two countries have been on a roller coaster; the last time they restored ties was in 2014 after five years of rupture following Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s 2009 claim that Iran “had sovereignty over Bahrain.”

The anti-Iranian rhetoric in Morocco has taken both political and religious dimensions, especially since 2005. Moroccan officials have been very skeptical about the impact of the penetration of Shia Islam into the country and the emergence of a Shia community numbering in the few thousands, mainly in the northern city of Tangiers. Some 300 Moroccan Shia from the city were reported to have been jailed in the country as part of the authorities’ crackdown on Iran’s alleged “desire for regional domination.” Expressing his opposition to the government’s treatment of the Shia in the country, Idriss Hani, a leading intellectual leader of the clandestine Shia community, points out that Morocco has not had much experience with Salafi and Wahhabi Islam, whose point of view is that Shia Islam is considered apostasy. To him, this anti-Iranian, anti-Shia sentiment has derived from the rival Saudi Sunni influence and Morocco’s long-standing relations with Gulf monarchies.

The other political vendetta is between Hezbollah and the Moroccan authorities. Some observers suggest that Hezbollah and the Polisario have grown closer in the wake of the arrest of Lebanese businessman Kassim Tajeddine in Casablanca on March 16, 2017, while travelling from Guinea to Beirut, based on an extradition order issued by the US authorities. His name was on the US Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Global Terrorist list in May 2009, as “an important financial contributor to Hezbollah.” He was a suspect in funneling money to Hezbollah from his businesses, including Tajco, a property and investment group. This may help explain why the party may want to assist the Polisario, as well as shed some light on the potential correlation between its connection to the organization and the fortunes of relations between Morocco and Iran.

Mixed Reactions and Distant Interpretations

The urgency and decisiveness of Morocco’s diplomatic rift with Iran implies some conviction that a Hezbollah-Polisario deal will be executed.

Iran rejected Morocco’s accusations and its Foreign Ministry spokesman Bahram Qassemi emphasized the Islamic Republic’s principles of respecting other states’ sovereignty and security and non-interference in their affairs. A similar denial of involvement came from Hezbollah in Beirut. Its statement pointedly rejected Morocco’s accusations of providing weapons to the Polisario Front as an “unsubstantiated charge,” saying that it implied foreign “pressure” had been put on Rabat. Hezbollah expressed regret that “Morocco is resorting to pressure from the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia to direct these false accusations.”

From his side, M’hamed Khadad, the Polisario’s coordinator with the UN mission MINURSO, emphasized that his group “has never had military relations and hasn’t received weapons or held military contacts with Iran or Hezbollah”; he defied Morocco to provide any evidence to that end. Khadad also decried Rabat’s alleged neglect of the dialogue called for in Security Council resolution 2414 of 2018, which called on the parties to “resume negotiations under the auspices of the Secretary-General without preconditions and in good faith.” Indeed, a fifth round of UN-brokered talks at Manhasset has not resumed. Algeria also rejected as “totally baseless” the Moroccan narrative that a diplomat at the Iranian embassy in Algiers provided caches of arms to the Polisario Front.

However, the urgency and decisiveness of Morocco’s diplomatic rift with Iran implies some conviction that a possible and well-planned Hezbollah-Polisario deal will be executed. According to a source familiar with the royal palace’s strategy in Rabat, “there may be an element of seizing the political moment here, but it seems unlikely that the Moroccan government would entirely make something like this up.” However, the source stresses that “the Moroccan intelligence services would not mess around with something as sensitive as this [matter].”

A Silver Lining?

The new political saga of an Iranian-Hezbollah alleged “conspiracy” against Morocco has been a double-edged sword in the maneuvering of the protracted conflict in the Western Sahara. On the one hand, it adds to the existing turmoil and lack of trust between Morocco, Algeria, and the Polisario Front in fully embracing the UN-renewed plan of seeking “a just, lasting, and mutually acceptable political solution, which will provide for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara.” Instead of the one-year extension of the MINURSO mandate, the Security Council opted for only a six-month extension until October 31, 2018. There was already a sequence of bilateral charges of provocation.

The newly expanded Moroccan-Iranian rift seems to provide a window of some political opportunity for the Gulf states.

In early April 2018, Rabat complained about repeated incursions by the Polisario in Guerguerat, Bir Lahlou, and Mahbes, which represent the buffer zone east of the Morocco-built security wall. Morocco’s Ambassador to the UN Omar Hilale stated in a letter to the Security Council that Rabat considers any Polisario attempt to change the situation on the ground to be a cause for military action to deter the Polisario’s “provocations.”

On the other hand, the newly expanded Moroccan-Iranian rift seems to provide a window of some political opportunity for the Gulf states, some of which have supported Morocco’s decision to sever relations with the Islamic Republic. This can be seen as an element in the overall cost-and-benefit equation between the Gulf and the Maghreb, but also as cementing relations with good “allies” in the emerging anti-Iran coalition led by President Donald Trump, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Abu Dhabi, UAE, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed.

Inside the Gulf Political Boiler

Saudi Arabia expressed its solidarity with “the sisterly Kingdom of Morocco.” Saudi Foreign Minister Adel Al-Jubeir tweeted, “What Iran has done to the Kingdom of Morocco through its proxies (Hezbollah) training the so-called Polisario Front is solid proof of Iran’s interference.” He also renewed his charges against Iran in terms of “destabilizing the security of Arab and Islamic countries by igniting sectarianism, interfering in their internal affairs and supporting terrorism.”

The anti-Iran, pro-Morocco equation was also evident in the Emirati reaction. Anwar Gargash, the UAE minister of state for foreign affairs, echoed the long-standing relations with Morocco with this tweet: “Our policy and support for Morocco has a well-established historical legacy. Our attitude [towards Morocco] is constant [both] on good and bad days.”

However, the Qatari foreign ministry opted for more emphasis on preserving Morocco’s sovereignty “against any attempts aimed at undermining its unity,” in respect of the principles of international relations without evoking Iran. The foreign ministry said in a statement issued in Doha that “Qatar stresses the importance of respecting the principles governing relations between states, foremost among them respect for the sovereignty of states, non-interference in their internal affairs and the resolution of disputes through dialogue and peaceful means and internationally recognized methods.”

Some observers have argued that “Morocco has anchored itself as an ally of the GCC and of the United States—all at a fairly low cost

Other nations, as far as Djibouti and Romania, expressed support for the Moroccan position vis-à-vis Iran at a time of increasing pressure on Tehran to give up its nuclear ambition and retreat from Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. While on a visit to Rabat, Romanian Foreign Affairs Minister Teodor Melesçanu characterized Morocco’s stability as vital to regional and international security. He affirmed his country’s rejection of “any interference by states, organizations, political parties, or others, which can affect and harm the stability of Morocco.” Similar support of Morocco was also articulated by several regional coalitions, including the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

The Big Question

The crucial questions are why Morocco renounced its relations with Iran, and why now. After a four-year reconciliation process between Morocco and Iran, one must assess the temporal context and trajectory for answers regarding Morocco’s termination of this rapprochement.

First, Morocco’s rupture with Iran represents a double-bet calculation by the Moroccan leadership vis-à-vis the current agenda of the Trump White House and the anti-Qatar quartet (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and to lesser extent Egypt) in seeking the suffocation of Iran. Some observers have argued that “Morocco has not only advanced its own interests over the Western Sahara, but it has anchored itself as an ally of the GCC and of the United States—all at a fairly low cost.” Trump still holds grudges against Morocco for pledging a $12 million donation to the Clinton Foundation with the intention of supporting Hillary Clinton in her presidential bid against Trump. Back in April 2017, King Mohamed VI vacationed in Cuba and Florida for ten days while the Moroccan media predicted an impromptu Trump-Mohamed meeting to be held over a weekend in Mar-A-Lago. However, the meeting did not take place.

There is also the John Bolton factor. He was a fierce advocate of the right of self-determination for the inhabitants of Western Sahara and had a role in the Algeria-funded Polisario lobbying machine in Washington, before he joined the Trump team to serve as National Security Advisor. This may add an additional rough edge to Rabat’s ability to smooth relations with its ally across the Atlantic. After all, to be anti-Iran could sell well now in Washington and the Gulf. As the adage goes, Rabat can kill two birds with one stone.

Second, the opposing school of thought leans toward Morocco’s original strategy vis-à-vis neighboring Algeria, which the Moroccan establishment considers the muscle and the brain behind the Polisario Front facade. Severing diplomatic relations with Tehran could be no more than a timely strategy to expose the hidden deeds of the Algerian leadership in finding new venues of support for the Polisario Front—from the Middle East this time. The short six-month window, before the current MINURSO mandate expires at the end of October, may have created an atmosphere of anxiety in Rabat. It is most likely that some strategists at the royal palace rushed to the use of the alleged Hezbollah-Tehran-Algiers “collaboration card” as a tactical shift. The hope is to accrue more support from the United States, France, and Gulf allies, such as the Saudis and the Emiratis, after a two-month cycle of contention along the security wall in the Western Sahara.