American Senators—Republican, Democratic, and Independent—have been in the middle of an end-of-the-year push to rebuke Saudi Arabia before the expiry of the 115th Congress. Still upset about the gruesome murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the apparent role that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) had in orchestrating it, senators were looking to alter the status quo of American-Saudi relations under President Donald Trump.

There were four legislative maneuvers in the Senate––all of which enjoy varying degrees of popularity––that lawmakers were hoping to use to censure Riyadh. The most well-known—but also, perhaps, the one with the most potential hurdles—was S.J. Res. 54, or as it is more popularly referred to, the War Powers Resolution. Second, there was S. Res. 714, proposed by Lindsey Graham (R-South Carolina), which was a nonbinding measure that would decidedly chastise MbS for his role in Khashoggi’s murder as well as for the war in Yemen and the ongoing boycott of Qatar, a Gulf Cooperation Council member. Third, Senator Bob Corker (R-Tennessee) signaled that he will introduce his own resolution as an alternative to Graham’s. Several media reports suggested that Corker was angling to craft a joint resolution blaming MbS directly for Khashoggi’s murder. Finally, senators were also entertaining S. 3652, a wide ranging bill that was intended to punish Riyadh for both Khashoggi’s assassination and for its role in causing the humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

Regardless of which path members considered, Congress as a whole was unlikely to produce anything more than a symbolic rebuke of the Saudi government before the end of the current legislative session, and even that would come solely from the Senate.

Regardless of which path members considered, Congress as a whole was unlikely to produce anything more than a symbolic rebuke of the Saudi government before the end of the current legislative session, and even that would come solely from the Senate. In fact, as quickly as some of these maneuvers appeared to be gaining steam, their momentum slackened just as quickly. Nevertheless, members of the Senate were eager to get something done, no matter if it was merely symbolic, in order to lay the groundwork for the next Congress, when Democrats will take over as the majority party in the House of Representatives and will be more willing to punish Riyadh than the GOP majority has been thus far.

In the House, members have not completely given up on securing a vote before the end of the year. The Hill has reported that Reps. Ro Khanna (D-California) and Thomas Massie (R-Kentucky) are trying to secure enough support to pressure House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) to allow a “clean vote” on Khanna’s H.Con.Res. 142 which, like S.J. Res. 54, seeks to force the president to withdraw US troops from Yemen. However, on December 11, the House Rules Committee, which crafts the parameters governing how bills are debated and voted on before the full House, inserted a provision into a farm spending bill that would de-privilege Khanna’s concurrent resolution. Once the full House opted to adopt the rules package the following day, Khanna’s and Massie’s efforts were dealt a decisive blow. If this sounds familiar it is because the House Rules Committee used a similar maneuver with a bill about removing wolves from the endangered species list last October.

S.J. Res. 54: War Powers Resolution

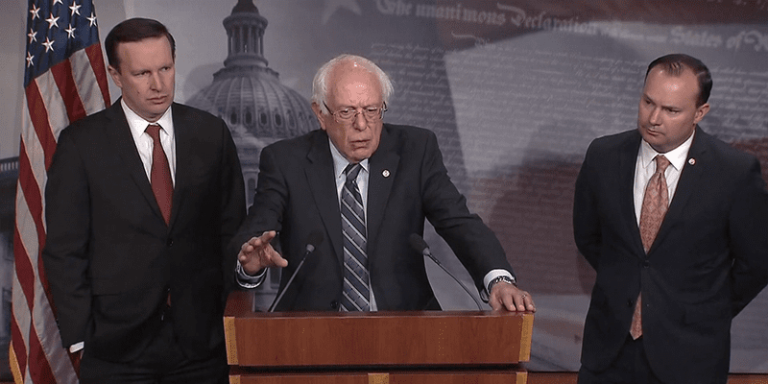

This resolution was originally introduced by Senators Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont), Mike Lee (R-Utah), and Chris Murphy (D-Connecticut) last March specifically to withdraw US military support for the Saudi-led coalition’s war with the Houthi rebels in Yemen. The resolution enjoyed modest support then, but it was not until November 2018—over a month after Jamal Khashoggi was murdered at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul—that a majority of senators agreed to move forward with a debate on the joint resolution.

As a joint resolution, if S.J. Res. 54 were to pass both chambers and survive the veto that the president has already threatened to use, it would be legally binding. This means that, hypothetically, the Trump Administration would be forced to remove US military forces from Yemen and end all support to the Saudi-led coalition, unless the troops’ operations are intended to fight al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula or the Islamic State offshoot in Yemen. However, since Congress granted itself the ability to invoke a War Powers Resolution in 1973, every single president has argued that it is an unconstitutional infringement on the president’s Article II authorities under the US Constitution, and President Trump is no different. If Congress gets the veto-proof majorities to pass S.J. Res. 54, a long shot at best, Washington could reach uncharted territory where the judicial branch—most likely the Supreme Court—would eventually have to make a decision about whether the administration should be forced to end its support for the war in Yemen.

If Congress gets the veto-proof majorities to pass S.J. Res. 54, Washington could reach uncharted territory where the judicial branch—most likely the Supreme Court—would eventually have to make a decision about whether the administration should be forced to end its support for the war in Yemen.

In the near term, however, passing the War Powers Resolution into law is an increasingly unlikely option. Even though S.J. Res. 54 passed the Senate floor by a vote of 56 to 41, the House is not obligated to take it up for consideration in a timely manner, thus all but ensuring that it would languish until the new legislative session begins next year.

S. Res. 714

Senator Lindsey Graham was once a supporter of Saudi Arabia and he had long been an important ally for Riyadh as he advocated for Washington to sell more and more weapons to the kingdom. Now, however, Graham is one of the most vocal and forceful critics of the young Saudi crown prince and he crafted S. Res. 714 specifically to denounce MbS for all of his destabilizing decisions since his ascent to the number one spot in the royal line of succession. This measure was legally nonbinding, but if it were to be adopted, it would have expressed the sense of the Senate that MbS should “be held accountable for contributing to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, preventing a resolution to the blockade of Qatar, the jailing and torture of dissidents and activists inside the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the use of force to intimidate rivals, and the abhorrent and unjustified murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.” Furthermore, the language recommended that the US government hold anyone involved in Khashoggi’s death, including MbS, responsible (e.g., through sanctions).

S.J. Res. 69: Supporting a Diplomatic Solution in Yemen and Condemning the Murder of Jamal Khashoggi

Senator Bob Corker has been most eager to put pressure on Riyadh, MbS, and the Trump Administration in response to all of the same issues Graham laid out in his resolution. When asked about MbS and the Trump Administration’s response to the CIA’s determination of the crown prince’s culpability, Corker said, “They [the administration] know that. I don’t know how many different ways I can express that. It’s important for the United States to speak with one voice, when we know that the crown prince was responsible for the murder of a journalist. That is not debatable. That’s not debatable.”

Corker opted for a joint resolution because he, like others in the Senate, felt that the Graham resolution was as toothless as it was nonbinding and did not even consider the sense of colleagues in the House.

In order to pressure the administration, on December 13 Corker proposed S.J. Res. 69 that called for supporting a diplomatic resolution for the war in Yemen and condemning the killing of Khashoggi. His resolution to cut off American assistance to the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen passed by a voice vote, a development that is seen as a rebuke to President Trump and the administration. Corker opted for a joint resolution because he, like others in the Senate, felt that the Graham resolution was as toothless as it was nonbinding and did not even consider the sense of colleagues in the House. Since Corker chose a joint resolution, it could put more public pressure on the president because, should it then pass the House, the resolution would go before the president and he could sign it and make a very public statement against MbS, or he could veto it and show a kind of junior-status level of fealty to the Saudis. Although the resolution would be legally binding, the tactic here is more of a public relations move because it does not include any tangible punishment for MbS, such as sanctions.

S. 3652: Saudi Arabia Accountability and Yemen Act

This was the most comprehensive of the four pieces of legislation. Its purpose, according to the sponsors, was “to support the peaceful resolution of the civil war in Yemen, to address the resulting humanitarian crisis, and to hold the perpetrators responsible for murdering [Jamal Khashoggi].” Under this law, the secretary of state, among other government officials, would need to submit reports to Congress detailing strategies for ending the fighting in Yemen and identifying the parties responsible for violence against civilians and possible war crimes. Additionally, this bill would have suspended future weapons sales as well as previously issued weapons importing licenses, although the president is afforded a generous national security waiver for this provision. The bill would also have prohibited US funds from being used to provide the in-flight refueling services to Saudi-led coalition aircraft, which the Pentagon previously said it was ending.

The bill also provided for the use of sanctions in some circumstances. First, it called for the US government to sanction anyone—whether part of the Saudi coalition or the Houthi rebels—who hinders humanitarian access or threatens the peace and stability of Yemen. This includes blocking seaports or ports of entry used by the United Nations or other groups or diverting goods intended for civilian relief. Sanctions would also have been levied against anyone providing material support to the Houthis, unless the president can certify that the group is making serious efforts to engage in the UN-led peace process. The final set of sanctions laid out in this bill would have been imposed on any Saudi government official or member of the royal family who “was responsible for, or complicit in, ordering, controlling, or otherwise directing an act or acts contributing to or causing the death of Jamal Khashoggi” or who helped the people responsible in any way. The word choice here was interesting because, if the bill passed alongside S. Res. 714, the Senate would be telling the administration it has to sanction anyone who can credibly be found to be “complicit in” the murder, while also adopting its own assessment that the Saudi crown prince himself was complicit in the operation.

One can imagine that the House leadership would shield the president from even a symbolic rebuke over his support for Saudi Arabia and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

As of this publication, the 115th Congress could very well conclude having done little to express its anger toward MbS. S.J. Res. 54, though it has garnered support in the Senate, is likely dead on arrival in the House. Infighting among the chairman (Bob Corker) and the ranking member (Robert Menendez, D-New Jersey) of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee also seems to have doomed S. 3652. That leaves a symbolic and nonbinding S. Res. 714 and Corker’s joint resolution as possible vehicles. However, it is uncertain if House GOP leaders would allow a vote on Corker’s joint resolution although it passed the Senate. As it stands, one can imagine that the House leadership would shield the president from even a symbolic rebuke over his support for Saudi Arabia and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.