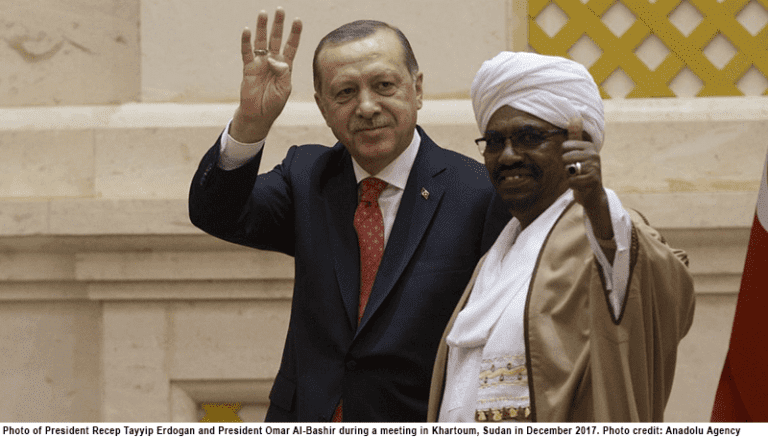

New Turkish footholds in the Red Sea have raised questions about Ankara’s long-term policy calculations in the region. In December 2016, Turkey signed an agreement with Djibouti, a small African country on the Red Sea coastline, to establish a free trade zone of 12 million square meters with potential economic capacity of $1 trillion. In September 2017, Turkey launched its biggest military base overseas in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia and a key city in the Horn of Africa. Soon after, following the lifting of US sanctions on Sudan in October 2017, the Turkish government showed great interest in investing in the country. As the first Turkish president to visit Sudan, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan signed $650 million in deals, including $300 million of direct investments.

For the first time since the Ottoman Empire’s defeat the First World War, Turkey finds itself entangled in the power struggle over the Red Sea.

Diversified Turkish investments in Sudan include a new airport in Khartoum, a free-trade zone in Port Sudan on the Red Sea, and private sector investments in power stations, cotton production, grain silos, and meat processing. More importantly, Erdoğan promised to raise the volume of Turkish-Sudanese trade by about $10 billion, and he purchased the right to rebuild Suakin Island, once a major port for the Ottoman Empire’s power projection in the Red Sea from the 15th to the 19th century. Turkey will benefit from the tourism potential of Suakin, which would enable Muslim pilgrims to travel to Jeddah by boat in their journey to Mecca by establishing a naval dock for operating civilian and military vessels.

Given that top-level Qatari military officials accompanied Erdoğan on his visit to Sudan, the Saudi-led quartet comprising Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt—which has enforced a diplomatic, commercial, and travel blockade against Qatar since June 2017—has become alarmed by Turkey’s new activism in the Red Sea. Moreover, Egypt’s deteriorating relations with Sudan, especially in light of its water disputes with Ethiopia, have put Ankara and Cairo on a collision course. A complex web of relations in the Horn of Africa risks militarization of the region following the war in Yemen. For the first time since the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in the First World War, Turkey finds itself entangled in the power struggle over the Red Sea.

What Does Turkey Want?

Turkey’s aspirations in the Horn of Africa are often portrayed as a revival of neo-Ottoman dreams, explained by ideological drivers. Despite the fact that the Turkish government has employed a neo-Ottoman discourse for domestic consumption and utilized Islamic identity in its foreign policy toward the Arab world, the ideological explanations fall short in explaining Turkey’s increasing activism in the Red Sea region—especially at a time when Ankara is retreating from the neo-Ottomanist vision of former Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and getting closer to Russia under the influence of Eurasianist bureaucrats in Ankara.

Turkey’s Red Sea activism is primarily driven by economic and strategic interests, not ideology.

Turkey’s Red Sea activism is primarily driven by economic and strategic interests, not ideology. First, the increasing significance of the Red Sea region allows Turkey to expand its financial interests, as the area has similarly attracted other regional and global powers. China, for example, established a free-trade zone in Djibouti as a part of its “One Belt, One Road” Initiative. Since coming to power in 2002, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party has invested in building partnerships in African markets, tripling the volume of trade with the continent to over $17.5 billion. The port sector is especially significant for Ankara as such investments would potentially yield higher revenues. A free-trade zone in Djibouti would serve as a trade hub that enables Turkey to export manufactured goods as well as raw materials to wider East African region. Likewise, with developing seaports such as Suakin Island, Turkey will play a larger role in the Sudanese export/import market—at a critical time since the lifting of US sanctions on Sudan in October 2017—and with neighboring countries including Somalia. Thanks to Suakin’s proximity and historical ties to Jeddah on the other side of the Red Sea, Turkey may also increase its share in religious tourism to Mecca.

Second, Turkey’s economic interests are not separable from its strategic calculations in the Red Sea region. In fact, Turkey’s largest military base was a culmination of close economic ties between Ankara and Mogadishu in recent years. While the volume of trade between Turkey and Somalia was $5 million in 2010, it reached $123 million in 2016. In securing support from the Somali government for the Turkish military base, the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency played a critical role by offering $400 million in aid to the country. Moreover, Turkish media reported that Ankara is invited to establish a military base in Djibouti, which already hosts US, French, Japanese, and Chinese bases.

The longevity of the GCC crisis has also influenced Turkey’s strategic choices. At the outset of the crisis, Ankara showed strong support for Doha while aiming not to alienate Riyadh. As the crisis deepened over time, however, Turkey’s balancing maneuvers have become irrelevant and have reinforced Erdoğan’s belief that his government is also a latent target of the embargo on Qatar. Thus, Ankara perceives that its interests are served by strengthening the Turkey-Qatar strategic axis and developing relations with potential allies like Sudan and Somalia. Such a strategic course will most likely influence Turkey’s long-term relations with major stakeholders in the Red Sea—mainly Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. After the Saudi-Iranian proxy war in Yemen, the Horn of Africa has witnessed increasing militarization by all parties, and thus, it has become an even more critical arena in the regional power play.

Irrevocable Rift in Turkey-Egypt Relations?

Turkey’s activism in the Red Sea rankles Cairo and further erodes already strained relations between Erdoğan and Egypt’s President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi due to the matter of the Muslim Brotherhood which Egypt designates as a terrorist organization. Last November, Egyptian authorities arrested 29 individuals on suspicion of espionage for Turkey. Ankara’s cordial relations with the Sudanese government constitutes a most sensitive development for Egypt, especially if it transforms into a military partnership. The disputes between Egypt and Sudan have historic roots, and Sudan has recently renewed its complaint at the United Nations to demand an Egyptian retreat from the Halayeb Triangle—the disputed territory at the Egypt-Sudan border that has been contested since 1958. Egypt accuses Sudan of sheltering exiled Muslim Brotherhood members and Sudan accuses Egypt of providing support to Darfur rebels. Cairo also perceives Qatar’s increasing investment in Sudan as threatening.

Turkey’s Red Sea activism poses yet another challenge to Washington-Ankara relations.

Turkey finds itself in the most complex web of power struggles in the Horn of Africa. What makes the Egypt-Sudan divide thornier is the reemergence of water disputes due to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile, the main tributary of the Nile. GERD has been under construction by the Ethiopian government since 2011, and in the early years, Sudan served as mediator between Ethiopia and Egypt. Lately, however, Sudan appears to support Ethiopia in the dispute. With negligible rainfall and heavy dependence on the Nile, Egypt is fearful of GERD’s potential repercussions such as a serious decline in agricultural production and an economic crisis. Upon completion, GERD is projected to produce 6,000 megawatts of hydroelectric power for Ethiopia with a storage capacity of 63 billion cubic meters of water in its reservoir—about one year’s flow from the Blue Nile. According to the Egyptian Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources, such a prospect will reduce Egypt’s share of Nile waters by 22 billion cubic meters per year, damaging both agriculture and hydroelectric production.

Cairo believes that the increasing support of Ankara and Doha to Khartoum has led to a growing alliance between Ethiopia and Sudan. In June 2017, Qatar removed hundreds of observers monitoring a ceasefire on Doumeira, a Red Sea island that is contested by both Djibouti and Eritrea. While that was a military move to repatriate soldiers at a time of tension with its GCC neighbors, it also sent a message to both countries after their positioning with the Saudi-led alliance in the ongoing Arabian Gulf crisis. As a result, Eritrea deployed its own armed forces on the island—a development that alarmed Ethiopia because of the ongoing hostility between the two countries after Eritrea’s bloody secession from Ethiopia during the 1990s. Last month, in coordination with the United Arab Emirates, Egypt chose to exploit the developments and sent troops to a UAE base in Eritrea as a message of deterrence to Ethiopia which, in turn, renewed its pledge to complete the GERD and aligned more closely with Sudan which swiftly deployed thousands of government militiamen on its border with Eritrea.

Turkey in the Lens of the Gulf Cooperation Council

Given their preoccupation with the war in Yemen, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi perceive Turkey’s Red Sea activism as a dangerous gamble. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have increased their military presence in various strategic ports in the Red Sea. They also pressured Sudan to join the Saudi camp in the Yemen war and to take a tougher position toward Iran. Although Turkey and Sudan recently declared that the Suakin Island deal has no military dimension, meetings of Turkish, Qatari, and Sudanese top army officers in Khartoum have agitated Riyadh. In addition to Turkey’s relations with Qatar, Turkey’s military presence in Somalia—and yet another potential military base in Djibouti in the near future—presents challenges to Saudi-UAE regional plans and drives a wedge between Ankara and the Gulf Cooperation Council. Even in simple economic terms, Turkey’s Suakin Island project is at odds with the Saudis’ Vision 2030 plan which places more emphasis on hajj tourism which will most likely be affected by Turkish plans.

What is viewed as Turkey’s encroachment into Arab politics in the Red Sea is also very much tied to Israel’s perceptions. Israel’s formation of strong relations with Mohammed bin Salman and Egypt’s Sisi is a key factor in power politics in the Horn of Africa. In the words of a former Israeli ambassador, Turkey’s “military cooperation agreements along the Red Sea with Somalia and Sudan are a direct threat not only to Egypt but also to Israel, whose vessels and planes transit through that sea on their way to Asia and Africa.”

With the deepening Gulf crisis, US military partners are feared to be turning weapons on each other in the Horn of Africa.

Thus, it is highly likely that Turkey’s military activism will be addressed in various ways by multiple players. The Saudis, for example, now consider cutting military and financial aid to Somalia, which is a member of the Arab League and is viewed as a crucial country for its strategic location to protect the “Arab homeland.” In reaction to the Somali government’s increasing ties to Ankara and Doha, the UAE is also considering ending its “pay, train, and equip” program for the special forces of the Somali National Army. Such steps may bring serious harm to Somalia as it tries to deal with its many security challenges. Given that various foreign powers support rival Somali politicians, the country may face domestic turbulence as well.

Yet Another Problem in Washington-Ankara Relations?

Turkey’s Red Sea activism poses yet another challenge to Washington-Ankara relations. Given that the Trump Administration has not effectively dealt with the GCC crisis, the race for military bases in the Horn of Africa may indeed escalate self-serving policies and thus put Turkey in a most difficult position. Washington perceives the Ankara-Doha axis from the Israeli and Saudi lenses; therefore, Turkey’s overseas military bases may likely be matters of discussion in the US Congress. Similar to accusations leveled against Qatar, Turkey is now being blamed for disrupting the Trump Administration’s anti-Iran coalition and possibly getting Tehran off the hook.

Given Washington’s strategic partnerships with Qatar and Turkey, the militarization unfolding in the Red Sea is an alarming trend for overall US policy toward the Middle East. With the deepening GCC crisis, US military partners are feared to be turning weapons on each other in the Horn of Africa as they coalesce around two camps, the Riyadh-Abu Dhabi axis versus the Doha-Ankara axis. As long as the Yemen war continues to destabilize the region, regional players are not likely to escape the dilemma of instability. As a critical first step, therefore, Washington needs to develop a consistent strategy to address the enduring and devastating war in Yemen—a war currently with no end in sight.