Despite the two countries’ tumultuous history and the fact that Iraq still owes Kuwait compensation from the 1990-1991 Gulf War, current Iraqi-Kuwaiti relations are on the mend. Kuwait wants Iraq to become a stable country that concentrates on internal development, as opposed to one that flexes its muscles in the region and renews old claims to Kuwait. For its part, Iraq wants Kuwaiti aid to help rebuild its heavily damaged cities and prevent extremists from crossing Iraqi borders to aid another possible Islamic State (IS)-type insurgency from emerging in the future.

However, the tense regional situation could upset the desire for improved bilateral ties. The squeeze on the Iranian economy that the Trump Administration is pursuing–– supported as it is by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain––as well as the so-called proxy wars in the region could lead to more regional conflicts and a possible direct clash between Tehran and Riyadh which will obviously count on Washington’s backing. Should this scenario transpire, Kuwait would come under pressure to side with the Saudis while the Shia-led government in Baghdad would feel compelled to side with Iran, thus—among other things—upsetting the progress that has been made in the promising Iraq-Kuwait relationship.

A Bitter History of Threats, Occupation, and Mistrust

The two countries have had a difficult relationship since the 1950s. Iraq was under a British mandate and received its independence in 1932 while Kuwait enjoyed British protective status until independence in 1961. In that year, which was three years after the collapse of the Iraqi Hashemite monarchy, Kuwait’s newly acquired independence was threatened by Iraqi strongman Abd al-Karim Qasim, who claimed its territory as part of Iraq. These threats prompted British troops to redeploy in Kuwait temporarily to protect the country’s sovereignty and British interests there. The United Arab Republic, comprised of Egypt and Syria, also sent troops to protect Kuwait at the behest of the Arab League and to replace British troops. Faced with these actions, Qasim eventually backed down from his threats of annexation.

Kuwaiti leaders have been wary of Iraqi designs on their oil-rich territory since that time. However, because it saw Iran as the greater threat, Kuwait aided Iraq during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War by providing Baghdad with billions of dollars’ worth of loans. After the conflict ended, Kuwait and other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) asked Iraq to pay them back, which led to renewed tensions with Baghdad. In 1990, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein accused Kuwait of overproducing to depress oil prices as well as diagonally drilling for oil into Iraqi territory. This caused a crisis in Iraqi-Kuwaiti relations as well as in the broader Arab world. Despite mediation attempts by Egypt and others, Saddam Hussein decided to invade Kuwait that summer and to incorporate it into Iraq, calling Kuwait Iraq’s “19th province,” and imposing a brutal occupation on the country. This invasion then prompted the United States to send troops—initially a protective force—to Saudi Arabia while it helped to assemble a large coalition of countries, Arab and non-Arab, to remove Iraqi troops from Kuwait by force in early 1991 and impose a tight sanctions regime on Iraq.

Kuwait suffered billions of dollars in damages as well as looted goods, and continued to see the United States as its protector against a revanchist Iraq that, in its view, could reemerge as an aggressor. Therefore, the Kuwaiti government was more than happy to assist the United States in the 2003 Iraq War and allowed its territory to be used as a launching area and a supply route for US and coalition forces. Although it was pleased to see Saddam Hussein and his Baath regime fall from power, Kuwait, like other Gulf Arab states, became alarmed at Iran’s growing influence in Iraq and the emergence of the Shia as the dominant political force there in the wake of the invasion.

Fear of Spillover

While Iraq’s internal convulsions after the 2003 US-led invasion kept the government focused on internal matters and not on expanding its borders, Kuwaiti authorities were fearful of a spillover from Iraq’s sectarian bloodshed. Kuwait has prided itself on its ability to maintain good relations between its Sunni and Shia citizens (the latter constituting about 30 percent of the population) and did not want to see such strife and violence in its own country. When a bomb exploded at a Shia mosque in Kuwait in 2015, killing 27 and injuring over 200, for example, Kuwaitis universally condemned the attack, and the Kuwaiti emir arrived at the scene of the bombing to underscore that this act of violence would not divide the Kuwaiti people. The bombing was claimed by the so-called Islamic State.

From the Iraqi government’s perspective, there was also concern that extremists from Kuwait and other Gulf Arab countries were infiltrating the country to join al-Qaeda in Iraq first and later IS. While Kuwaiti nationals in these terrorist organizations were not as numerous as, say, those from Saudi Arabia, the government in Baghdad saw such flows of extremist fighters—and funds from the Gulf Arab states in general—as trying to undermine the country’s stability and the Shia leadership of the new Iraq.

Abadi’s Diplomatic Overtures

The advent of Haider al-Abadi’s term as prime minister of Iraq in September 2014 helped to ease some of the concerns of Kuwait and other Gulf Arab states about Iraq’s government pursuing a narrow Shia agenda that would continue to suppress the Sunnis—a common perception held of his predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki. While Abadi was from the same Shia Daawa Party as Maliki, he was seen as more moderate and more willing to reach out to the Sunnis. The fact that Iraq and Kuwait were on the same side against IS also helped countries like Kuwait view Abadi in a more favorable light because of his push to rally the Iraqi people, regardless of sect, to fight the IS threat.

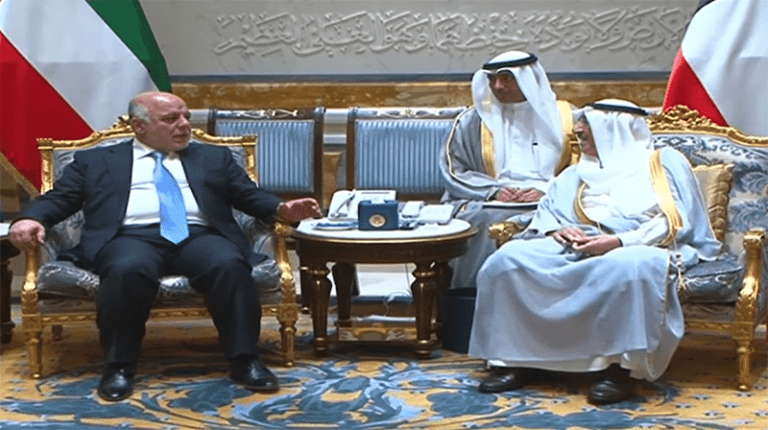

Abadi saw value in reaching out to Kuwait, which he first visited as prime minister in late December 2014. Regarding his meeting with Kuwaiti Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber Al Sabah, Abadi’s office said the talks focused on “the dangers of extremist groups, especially represented by ISIS’s criminal gangs in Iraq and the region” and fighting its “deviant ideology.” The two leaders also discussed a relief fund for Iraq, and the emir reportedly said he was ready to assist Kuwait’s “brotherly neighbor, Iraq.” On the touchy subject of Iraq’s reparations to Kuwait for the 1990-1991 Gulf War (about five percent of annual Iraqi oil revenues are supposed to be allocated for this purpose), one of Abadi’s economic advisors said at the time that the latest payment had been delayed until 2016 and added that Iraq would prefer to make investments in Kuwait instead, as that would “deepen bilateral relations between both countries.” This comment probably belied the fact that Iraq could not pay Kuwait at the time because it was running large budget deficits.

Abadi visited Kuwait again in June 2017 as part of a regional tour that also took him to Saudi Arabia and Iran. This visit, which came on the heels of the GCC crisis in which Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt instituted a boycott of Qatar, compelled Abadi to say he was not taking sides in the dispute and that he wanted good relations with his neighbors. Such a position coincided with Kuwait’s stance of not joining the boycott of Qatar despite having good relations with Saudi Arabia. In Kuwait, Abadi reportedly discussed again the 1990-1991 Gulf War compensation issue (though without publicly revealing the details) as well as plans for a Kuwait-hosted donor conference for Iraq’s reconstruction. As a sweetener for the conference, Kuwait pledged a $100 million grant for the humanitarian needs of Iraqis and the reconstruction of damaged cities that had been liberated from IS.

Kuwait’s Reciprocity by Hosting Donors for Iraq

The donor conference held in Kuwait in February 2018 marked a significant milestone in the relations between Iraq and Kuwait. It signaled that Kuwait now sees its neighbor as nonthreatening and friendly and that it is now willing to help Iraq financially. Moreover, the donor conference also represented the culmination of a long process of accepting Iraq back into the Arab fold by Sunni Muslim countries.

Although Iraqi officials came to the conference with a long wish list (about $88 billion for the rebuilding of their economy and the Iraqi cities damaged after IS control and the anti-IS campaign), the conference resulted in providing pledges to Iraq of $30 billion, mostly in credit facilities and investment. Iraqi Foreign Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari said the total pledged amount was lower than what Iraq needs, but he added, “we know that we will not get everything we want.” Still, the $30 billion figure was a substantial amount, and UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the conference “an enormous success.” As host of the conference, the Kuwaiti emir pledged $1 billion in loans and another $1 billion in investments to Iraq.

Some observers have speculated that many of the conference attendees could pledge more in the future but were awaiting two developments: the outcome of Iraq’s May 2018 parliamentary elections (which is still unclear given the recount of votes) and whether the Iraqi government would crack down on corruption in a serious way. Most attendees wanted Abadi to remain as prime minister, but his bloc’s third-place showing in the elections, and the maneuvering of the other Shia-led blocs, may have given donors some pause. On the other hand, the first-place finish by the bloc led by the firebrand Shia cleric, Muqtada al-Sadr—who had refashioned himself as an Iraqi nationalist not beholden to Iran and visited Arab Gulf countries in 2017—may be a positive sign for the future. Although after the elections he temporarily flirted with an association with Hadi al-Amiri, a pro-Iranian leader of the mostly Shia Popular Mobilization Forces, Sadr now has a firm alliance with Abadi that may blunt some Iranian influence on policymaking in Iraq. At this point it is not clear if Abadi will retain the premiership. If, once the political bargaining is done, Abadi does not remain at the helm, Kuwaiti-Iraqi relations may suffer, as Abadi has spent time courting the Kuwaiti leadership and the Kuwaitis are probably uncertain about the effectiveness and the intentions of the other Shia political leaders.

Implications for the United States

It is in the interest of US national security for Iraq and Kuwait to put the past behind them and continue to cooperate and deepen bilateral relations. Such a policy would reduce lingering tensions from the 1990-1991 Gulf War and help in rebuilding the damaged Iraqi cities, most of which are in the Arab Sunni areas of Iraq where mistrust of the Shia-led government is still predominant. If the reconstruction of these areas is delayed or seen as insufficient, another insurgency could reemerge, and that would be in no one’s interest except for that of the extremists. Thus, it behooves US policymakers to encourage this rapprochement and persuade the Kuwaitis to be even more generous in providing economic assistance to Iraq. But increased assistance will not come easy when there is growing donor fatigue, and the United States itself has extended only a $3 billion credit line to Iraq.

Of more concern than the reconstruction financing issue is the potential for new hostilities between the United States and Iran as well as the possibility of direct clashes between Tehran and Riyadh. The Trump Administration’s policies of isolating Iran after the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, coupled with the pressure Washington is putting on European countries to cease purchasing Iranian oil, could lead Tehran to lash out in the region. That scenario would probably play well to the hawks in the Trump Administration who may be eager for a fight with Tehran, but it could also set back some promising developments like the Iraqi-Kuwaiti rapprochement. Further, Kuwait could be “exposed to direct attack or subterfuge” by Iran, and rifts in Kuwaiti society could open if Kuwait were likely to side with the Saudis in a clash with Iran. As mentioned earlier, Iraq, because of its Shia ties, would then feel compelled to align with Iran.

Hence, US policymakers would be well-advised to scale back the heated rhetoric on the Iran issue because it runs the risk of precipitating a war—one that could have unintended consequences such as the backsliding of progress in Iraqi-Kuwaiti relations.