The Egyptian government has deepened its cooperation with Israel on strategic and economic matters in order to root out the extremist threat in the Sinai Peninsula and bolster Egypt’s economy. This policy particularly concerns natural gas, which has the potential to bring in much needed foreign exchange earnings. The growing ties have been facilitated by meetings between Egyptian and Israeli officials in recent months, partly with an eye toward mollifying the Biden Administration and Congressional Democrats who have been highly critical of Egypt’s poor human rights record.

For its part, the Egyptian public, while generally not averse to trade with Israel, remains wary of warmer relations with their neighbor until a just peace deal between Israelis and Palestinians is concluded. Should Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing allies continue to dominate the Israeli polity, however, such a deal is unlikely to materialize. Hence, Cairo will probably not alter its position that a two-state solution, along the lines of the Arab Peace Initiative (API) of 2002, is the preferred course of action, despite pressure from Israel that Trump’s “Peace to Prosperity” plan of 2020 is the one that should be adopted.

Sensitive, Bilateral Cooperation in the Sinai

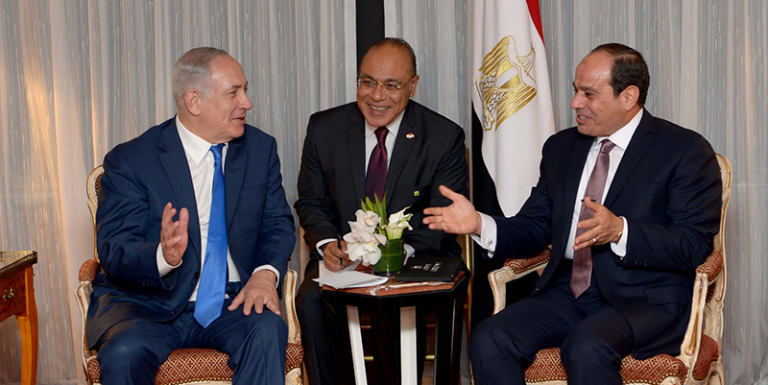

Strategic ties between Egypt and Israel have never been as close as they are today under President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, and both he and Netanyahu reportedly communicate with each other fairly often. Under Sisi’s administration, Egypt and Israel have closely cooperated on counterterrorism measures, particularly against the main terrorist group in the Sinai called Wilayat Sinai, formerly known as Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, an affiliate of the so-called Islamic State (IS). In the minds of both Israeli and Egyptian officials, this IS group must be defeated at all costs, and Hamas, the Palestinian group that controls the Gaza Strip, must be contained.

Concerning cooperation on the former, Israel has allowed significant Egyptian military units and armaments to be deployed to the northeastern section of the Sinai Peninsula in contravention of the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, which restricts the number of Egyptian personnel and armaments in this zone. For its part, Egypt has reportedly given the Israelis the green light to

undertake drone and other air strikes in this area against extremist targets. One report has indicated that Israel carried out over 100 air strikes in the Sinai between 2015 and 2018. When this Israeli military activity in the Sinai was exposed in a New York Times article in early 2018, the Sisi government was so sensitive about the issue, for fear of a public backlash, that it

issued vehement denials. Because of a news blackout on security developments in northern Sinai, it is hard to determine what has been going on in that area since, but presumably this cooperative military relationship is continuing. Despite a reduction in terrorist attacks, the Islamic State affiliate there remains a threat; as long as these militants have not been eradicated, it is likely that such military cooperation in the Sinai between Egypt and Israel will continue.

Despite a reduction in terrorist attacks, the Islamic State affiliate there remains a threat; as long as these militants have not been eradicated, it is likely that such military cooperation in the Sinai between Egypt and Israel will continue.

At the same time, both Egypt and Israel have an interest in containing Hamas, which has been in charge of the Gaza Strip since 2006 when military skirmishes resulted in the expulsion of the secular-nationalist group, Fatah, from that area. Egyptian officials have long been wary of Hamas, which grew out of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood, as the Brotherhood remains the Sisi government’s main domestic and ideological foe and one that attacks it from media outlets abroad. The Sisi government also believes that Hamas often disregards extremist elements in Gaza aiding the terrorist insurgency in the Sinai. From Israel’s perspective, Hamas is an enemy that has neither given up violence nor recognized Israel’s existence. Both Egypt and Israel have cooperated in closing down tunnelsconnecting the Sinai to Gaza, which have been used to smuggle people and goods in both directions. Egypt has also kept the border crossing between Gaza and the Sinai closed for the most part, generally only opening it for certain periods to allow for medical and family visits.

However, Egypt has also played a dual role regarding Hamas. Although it favors Fatah in Palestinian politics (the party dominating the Palestinian Authority in the occupied West Bank), it has often hosted meetings between the two Palestinian factions in the interest of supporting Palestinian unity, with the meetings occurring in Cairo in February and on March 16, in anticipation of Palestinian elections later in the year. During this time, Egypt even opened the border crossing in Rafah by the Gaza-Sinai border to allow for the Hamas delegation to travel to Cairo and as a goodwill gesture to Palestinians living in Gaza. It seems that the Israelis do not mind the Egyptians playing this mediation role, and even find it useful, because these links allow Cairo to defuse periodic military flare-ups between Hamas and Israel that have occurred over the past couple of decades.

In mid-January 2021, the director of Egyptian General Intelligence, Abbas Kamel, traveled to Ramallah in the West Bank to meet with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, Palestinian intelligence chief Majed Faraj, and Jordanian intelligence chief Ahmad Husni. The meeting was billed as a gathering to advance the peace process and to discuss upcoming Palestinian elections. Although no mention was made of Kamel holding a separate meeting with Israeli intelligence officials, it seems likely that one was probably held, given that the Israeli government was only a few miles away. In May 2020, the head of Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency traveled to Cairo to meet secretly with Egyptian officials, according to Israeli press reports. The meeting was supposedly geared to alerting Cairo about Netanyahu’s annexation plans for the West Bank. While nothing came of this visit because the annexation plan was put on hold, such meetings underscore the close consultations between the two countries.

Growing Economic Links, Particularly over Gas

Although trade between Egypt and Israel along with joint projects like Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZs), which allow for products to be manufactured and exported to the United States without tariffs, have existed for a long time, what is new is the potential for large, joint gas projects. In 2005 Egypt started to export natural gas across the Sinai into Israel, but such exports stopped in 2012 as Egypt’s domestic demand for gas rose and insurgents in the Sinai targeted the gas pipeline. Now it appears that gas in large quantities will flow in the opposite direction. Last month, Egypt’s Minister of Energy Tarek al-Molla traveled to Israel to meet with his Israeli counterpart, Yuval Steinitz, as well as with Prime Minister Netanyahu, to discuss a major collaborative project. Gas from Israel’s large offshore Leviathan field in the eastern Mediterranean would be transported via a new pipeline on the seabed to connect with liquefication facilities in Egypt. Currently, gas from the Leviathan field is being sent to Egypt via a pipeline that runs to the Sinai Peninsula. The goal of this new project, according to an Israeli official, would be to use these facilities to export gas to Europe, where demand is rising. Undoubtedly, Israel sees this collaboration as a way of tying the Egyptian economy to Israel so that any future Egyptian leader would think twice about rolling back bilateral relations.

From Egypt’s perspective, this deal fits into its plans to become a major regional hub for natural gas. In 2015, a large gas field, called Zohr, was discovered in Egyptian territorial waters in the Mediterranean, and Egypt has been the force behind the establishment of the “East Mediterranean Gas Forum” which includes Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinians. The forum aims to increase cooperation among gas producers and transit countries.

Some Egyptian officials still worry about Turkey’s role in Libya and its continuing support for Egyptian Muslim Brothers, many of whom have been given safe haven in Turkey where they broadcast media attacks on the Sisi government.

What most of these countries have in common right now is opposition to Turkey’s desire to expand the jurisdiction of its territorial waters in the eastern Mediterranean. Although there have been some recent reports that Turkey and Egypt may be trying to improve relations, other reports suggest that Cairo may not be fully on board. Some Egyptian officials still worry about Turkey’s role in Libya and its continuing support for Egyptian Muslim Brothers, many of whom have been given safe haven in Turkey where they broadcast media attacks on the Sisi government. Israeli-Turkish relations are also strained not only because of the gas issue in the Mediterranean but because of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s support for Hamas. It was not lost on observers that Israel participated in naval exercisesearlier this month with Greece, Cyprus, and France, all of which have problems with Turkey.

Outside of cooperation on gas, Egyptian officials hope to lure Israeli tourists back to Egypt, particularly to the Sinai resort towns like Sharm el-Sheikh. In early March of this year, Israeli Minister of Intelligence Eli Cohen met with Egypt’s Deputy Minister of Intelligence Nasser Fahmi in Sharm el-Sheikh and said Egypt was doing “everything possible” to make the Sinai safe for Israeli tourists. Interestingly, Cohen was reportedly accompanied by 60 Israeli officials and businesspeople, indicating that both countries hope to boost tourism in the coming years.

The Egyptian Public Remains Cool to Enhanced Ties

Significantly, the report about the aforementioned meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh included very little media presence, “at Egypt’s request.” The Egyptian public, while desirous of the continued peace between Egypt and Israel, is still not comfortable with the idea of warming ties between the two countries as long as the Palestinian issue is unresolved. This causes Egyptian officials, including Sisi himself, to tread carefully at times. For example, an Israeli news outlet reported that Netanyahu wanted to visit Egypt before the upcoming Israeli elections, but Sisi reportedly asked the Israeli leader to express support for a two-state solution as a precondition for visiting Cairo, something that Netanyahu was unwilling to do.

The Egyptian public, while desirous of the continued peace between Egypt and Israel, is still not comfortable with the idea of warming ties between the two countries as long as the Palestinian issue is unresolved.

Polling in 2020 conducted by the respected Zogby Research Services found some interesting data on Egyptian public attitudes toward Israel and the Palestinian issue. The question “How important is it that there be a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?” revealed that 79 percent of Egyptians thought it was “very important”; 15 percent said “somewhat important”; and only 6 percent said “somewhat unimportant or not important at all.” Concerning the question about the possibility of Israeli annexation of large parts of the West Bank, 75 percent of Egyptians believe that cooperation with Israel should come to an end if that were to occur.

Similarly, the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies’ Arab Opinion Index in its 2019-2020 surveyof public attitudes toward Israel in Egypt found almost identical results. A full 85 percent of Egyptians responded that they oppose recognizing Israel, although a peace treaty has existed between Egypt and Israel since 1979. Moreover, almost three-quarters of Egyptians believe that the question of Palestine concerns all Arabs and not the Palestinians alone, indicating that the general public in Egypt still has great affinity to the Palestine cause.

Adjusting to, and Trying to Placate, the New Biden Administration

These public attitudes and the advent of the new Biden Administration have put the Sisi government in a sort of a quandary. On the one hand, Sisi wants to show Washington that he can be helpful in the peace process and be cooperative with Israel, in part to deflect attention from Egypt’s poor human rights record, which Secretary of State Antony Blinken and

Democratic leaders in Congress have raised. On the other hand, there are limits to how far he can go in cooperating with Israel, especially if the right wing there remains ascendant. Sisi cannot drift too far from the Arab Peace Initiative without incurring a domestic backlash, but neither can he get into a major dispute with Israel for fear of scuttling new strategic and economic links and ending the support he has received from pro-Israel supporters in the United States.

In the meantime, Sisi has shown a willingness to display a more tolerant religious side to Egypt by allowing Judaism to be taught in Egyptian schools, as part of studying the three Abrahamic faiths, and by providing government funds to restore some synagogues in Egypt that had fallen into disrepair. These gestures are designed in part to lure Israeli tourists back to Egypt, but they are also meant to make a favorable impression in Washington. However praiseworthy, these gestures do not address the overall human rights climate in Egypt, which remains highly problematic, as simple dissent can land one in jail. Moreover, if Biden and his team decide to put off a major push in the peace process, Egypt’s usefulness to Washington becomes less important since Cairo would then have fewer cards to play. Hence, while enhanced Egyptian-Israeli relations can work to Cairo’s benefit, what would really make a difference for Egypt in Washington is opening up the political space, improving human rights, and curtailing repression.19