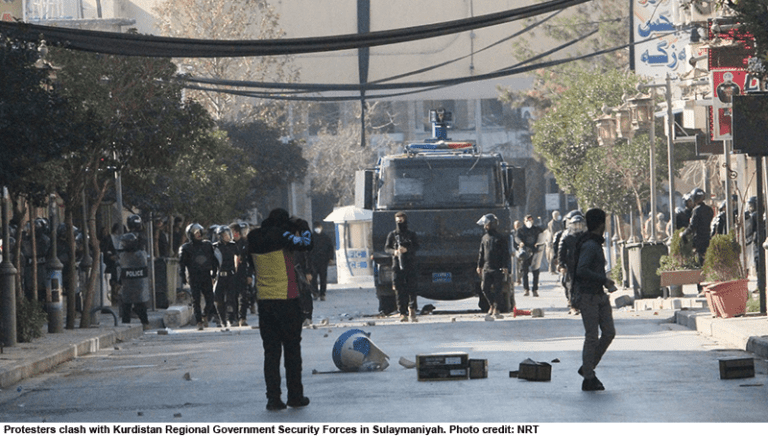

The recent Iranian protests have overshadowed the chaos in Iraqi Kurdistan. Last December, thousands-strong protests rocked Sulaymaniyah and Halabja, cities in Iraqi Kurdistan with a population of two million and home to strong Kurdish opposition to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). In clashes with security forces, five protesters lost their lives and a hundred were wounded. Given that protesters set fire to the offices of the ruling parties, namely Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and late Iraqi President Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), Kurdish authorities justified their harsh measures with security claims. The crackdown on the opposition media was particularly violent, reminiscent of the KRG government’s response against the October 2015 protests in Sulaymaniyah. Among the hundreds of arrested during the demonstrations were many journalists from the largest opposition media group, Nalia Radio and Television (NRT), whose Kurdish and Arabic channels were shut down due to their alleged incitement against the government.

Despite the KRG’s later decision to release journalists and allow the NRT’s operations to resume, such a turbulent episode has left enduring marks. The Gorran Movement and the Kurdistan Islamic Group (Komal) have withdrawn from the KRG, emptying five positions in the 21-minister cabinet. Also, the Gorran-affiliated Kurdistan parliament speaker, Yousif Mohammed, resigned in protest over the ruling KRG elite. Moreover, Gorran unilaterally suspended its 25-article pact with the PUK—originally signed in Sulaymaniyah in 2016—in the presence of the charismatic founders of Gorran and the PUK, Nawshirwan Mustafa and Jalal Talabani, respectively. Both leaders passed away recently.

Amid such increasing tensions, Iraqi Kurdistan has already entered the election atmosphere. The Kurdish opposition parties have accused the KDP and PUK of failing the nation before and after the independence referendum, demanding dissolution of the current cabinet and formation of a national representative committee to pursue negotiations with Baghdad until the Kurdish parliamentary elections, expected to be held in summer 2018. The Sulaymaniyah protests have revealed a deep split in Iraqi Kurdistan. By pitting Sulaymaniyah against Irbil, the seat of the government and home to Barzani, Baghdad aims to capitalize on the intra-Kurdish divide.

The Kurdish Referendum Invited Further Divisions, not Unity

A closer look at the sentiments behind the protests reveals how long-term frustrations fuel the Kurdish opposition. Topping the list are the quest for timely payments of public employee salaries, complaints about widespread corruption and nepotism, improvement of public services, and new presidential elections—the very same demands of the protesters during the October 2015 demonstrations. The threat of the so-called Islamic State (IS) had helped KRG officials to quell the protests with future promises and to extend Masoud Barzani’s presidential term once again. Earlier, inspired by the Arab Spring, protests in 2011 led to the KRG’s approval of a parliamentary bill that consisted of 17 points of agreement between the government and the opposition, including initiation of structural reforms and fighting against cronyism and corruption. The lack of systemic reforms, however, has remained a major problem. Although the KRG has introduced some measures for accountability in the oil sector, the opposition claimed such reforms as being too little, too late.

As the IS threat vanished, the KDP’s push for an independence referendum in September 2017 was a major gamble that could have boosted the ruling elite’s legitimacy and authority. The referendum galvanized Kurdish feelings of unity as one nation. Such high emotions, however, turned into major frustrations with the Iraqi military operations in the territories around Kirkuk disputed between the KRG and the central government in Baghdad, in the aftermath of the referendum. The Kurdistan region not only lost massive oil revenues but also faced an economic embargo, including the blockade of international flights that was imposed by the central government.

Specifically, after the loss of Kirkuk to Baghdad, the KRG’s oil production fell from 550,000 to 250,000 barrels per day. The flight ban severely harmed commercial activities, having a direct effect on international investment. Airport cargo imports almost disappeared, down from monthly averages of 2,500 tons before the blockade to 10 tons. About 4,000 tourism and travel companies were affected, laying off almost 12,000 workers. The KRG’s overall income decreased from $565.5 million a month to $337.4 million, marking a 40-percent drop. The dire outcomes have led the ruling parties to accuse each other of treason, while opposition parties forcefully demanded the resignation of the government.

Baghdad’s Power Play over the Intra-Kurdish Fight

An analysis of Iraq’s 2018 budget for the Kurdistan region exposes how Baghdad aims to capitalize on intra-Kurdish divisions. Instead of sending the salaries of public employees through KRG authorities in Irbil, the central government plans to send funds directly to the Sulaymaniyah governorate—which is currently run by a Gorran Movement member. In bypassing Irbil, Baghdad aims to cultivate better relations with Kurdish opposition groups and to embolden Gorran’s influence, thus weakening the grip of both the KDP and the PUK over Sulaymaniyah and Halabja. According to the proposed budget, “provinces of the Kurdistan region” will receive their share in accordance with the population; therefore, Sulaymaniyah will receive 40 percent while Irbil and Dohuk will get 36 percent and 24 percent, respectively, out of the $5.6 billion total. Such allocations would also mean that the KRG will receive 12.67 percent, falling short from its demand of 17 percent—which has been its traditional fixed share. Baghdad’s budget lists 682,021 KRG employees to be paid, whereas Kurdish authorities state that the number of public sector personnel is about 1.2 million, which normally costs $772 million monthly. Accordingly, Baghdad would only allocate $392 million for public employees and the rest of the burden will be on Irbil’s shoulders.

Thus, with unresolved disputes, Baghdad’s direct allocation to Sulaymaniyah will only harm Irbil’s financial plans. Finding international loans has become more difficult as the KRG struggles to repay the loans that were taken due to its colossal budget deficits in recent years, reaching $20 billion in total. In a desperate move, Irbil announced new austerity measures for 2018, including reducing the salaries of “high-earners” in the public sector as much as 33 percent.

In line with its strategy of direct payments to provinces, Baghdad has also begun providing salaries to KRG ministries directly, along with oversight and auditing of accounts. Having long complained about corruption and mismanagement, the Kurdish opposition welcomes such steps by the government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. In the words of a leading figure during a protest march on December 19, 2017, “We call on Abadi to help us. We are Iraqis. Do not negotiate with KRG. Please give us the salaries.”

During the first week of January, after the arrival of the first delegation to visit Baghdad since the Kurdish referendum, three opposition parties—namely Gorran, Komal, and the Coalition for Democracy and Justice—met with several Iraqi leaders, including Abadi and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, to the chagrin of KRG officials in Irbil. On the eve of Iraqi elections, Iraqi Shia leaders’ interest in Kurdish divisions is also notable. In defending the demonstrations in Sulaymaniyah, for example, influential cleric Muqtada al-Sadr stated1 that the people’s march against corruption is commendable and that protesters’ security must be ensured.

Baghdad also seeks to benefit from divisions between the KDP and PUK as well as rifts within the PUK leadership. The central government plans to pay the salaries of the Kurdish Peshmerga through the Iraqi Army’s budget, ensuring that the PUK Peshmerga gets paid by Baghdad and not Irbil. KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani aims to defend the KDP-PUK alliance with a joint list in the Iraqi elections in May 2018 and a joint declaration for scheduling a date for the Kurdish parliamentary and presidential elections. A major challenge for Irbil, however, is the disunity of the PUK after the passing of Jalal Talabani. This was followed by the deterioration of the health of the current PUK leader, Kosrat Rasul. The party’s prominent members, including Qubad Talabani, Bafel Talabani, and former deputy leader Barham Salih, may face tough competition in the party congress in the next few months; therefore, they may be open to negotiations with the Abadi government independently.

Divisions within Divisions: The New Generation

Among the opposition, the New Generation movement led by Shaswar Abdulwahid is noteworthy. A small political party based in Sulaymaniyah with a limited following, the New Generation was founded following the Kurdistan independence referendum. Abdulwahid, a prominent businessman who owns the NRT media group, initiated the “No for Now” campaign for boycotting the referendum, with the claim that the referendum was “an excuse by Kurdish leaders to remain in power.” Not surprisingly, Abdulwahid and the NRT channels were portrayed as Iran’s pawns during the highly emotional referendum atmosphere. Last month, Abdulwahid was detained for a week due to his alleged role in violent protests in Sulaymaniyah and Halabja; he was released on bail.

The New Generation is rooted in the Gorran tradition, representing a younger “urban generation” that is at odds with the older “mountain generation” in Kurdish politics. Criticism of the tribal power structure and family networks is a common thread among the urban poor as well as the growing educated middle class in Kurdistan. The rise of Gorran, literally the “movement for change,” under the leadership of Nawshirwan Mustafa was remarkable indeed. Mustafa encouraged young leaders to take critical roles in the party, denouncing his previous home party, the PUK, which had become out of touch. The Gorran experience has proved that Kurdish opposition parties may prosper if they are able to gain the sympathy of the urban youth.

Despite facing hardships in competing with older parties in the elections, the New Generation signals a search for alternatives among members of the young electorate, especially in Sulaymaniyah and Halabja. Within the span of a few months, charismatic figures who dominated the Kurdish political scene in the past few decades have left a power vacuum: Talabani and Mustafa passed away, and Barzani resigned. The challenge for the young leaders, from Shaswar Abdulwahid to Qubad Talabani, is how to earn popular legitimacy and respect. Second generation Barzanis and Talabanis enjoy family names and reputations, albeit also bearing the liability that comes along with them. Abdulwahid and other “non-royal” challengers may appear attractive to the urban poor; however, they will need to prove their leadership capabilities. After the New Generation’s very first party congress, Abdulwahid has already faced challenges of unity within.

Implications for Washington

The Sulaymaniyah protests were the latest incarnation of deep-rooted polarization in Iraqi Kurdistan. This time, however, Baghdad’s active role in interfering in intra-Kurdish divisions was most noteworthy. Such a “divide-and-rule” strategy toward the Kurds makes Washington’s policy to save the unity of Iraq more challenging.

On the one hand, the Abadi government appears to have an upper hand in future negotiations with the KRG because of Baghdad’s better relations with different Kurdish factions. On the other hand, by seeking the separation of Sulaymaniyah from Irbil, the Iraqi government may be providing fuel to current turmoil in Kurdistan—an outcome that does not serve the stability of Iraq, if it is to remain united. The recent statements of Mala Bakhtiar, head of the PUK’s political bureau, signal the potential dangers ahead: “We will be the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan if we win one seat, and we will be the Patiotic Union of Kurdistan if we win 100 seats … We have armed forces, and therefore no force can disarm us.”

For Washington, instability in Kurdistan or in Iraq is not a desirable outcome, especially at a time when Iran’s shadow over Iraqi domestic politics is more visible than ever. With both Iraqi and Kurdish elections on the horizon in 2018, the United States is better off trying to cut the Gordian knot sooner rather than later by taking a leadership role to bring parties together for resolving the issue of Iraq’s disputed territories. In addition, Baghdad should be reminded of the fact that disputed territories and other key issues cannot be peacefully resolved as long as multiple Kurdish actors with armed forces are forging shifting alliances with different Iraqi parties, including Shia militia leaders. Thus, with the support of Washington, the Iraqi government should focus on helping, and not punishing, Kurdistan, for conducting institutional reforms including political accountability, economic resilience, and transparency in the oil sector.

1 Source is in Arabic.