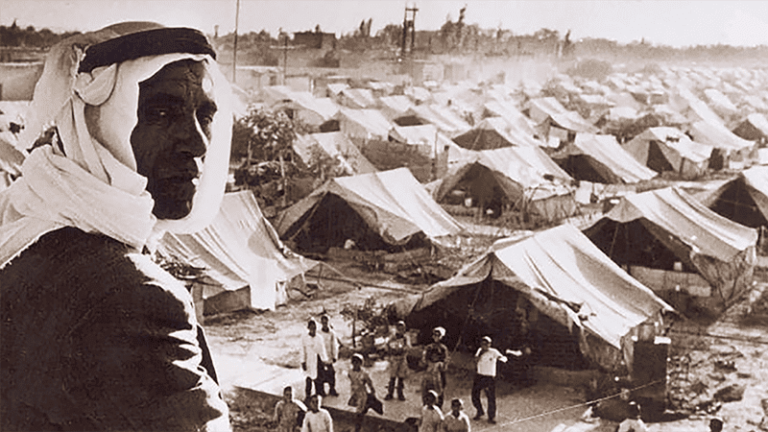

The Nakba, a term that describes events in Palestine surrounding the establishment of the State of Israel from 1947 to 1949, which included the ethnic cleansing of the vast majority of Palestine’s indigenous Arab inhabitants, is much more than a historical moment. The Nakba is an ongoing process. To properly understand it, what drives it, and where it is going, it is crucial to see the Nakba as a long-running process of connected events of varying scales that all share a common goal: the replacement of Palestinians with Jewish Israelis. While the ethnic cleansing of Palestine around 1948 was a massive, paradigm altering event, it fits into a pattern that continues to this day and, importantly, it sheds light on what can be expected for the future of the Zionist project in Palestine.

A Process of Replacement

From 1947 to 1949, some 750,000 Palestinian Arabs were made refugees, and more than 500 Palestinian towns and villages were depopulated, most through direct attacks by Zionist militias that later became the Israeli Army. This major historical moment was perhaps the most consequential in the last century of Palestinian history. The majority of Palestine’s Arab inhabitants, some two-thirds, were forced from their homes and denied return, severing them from family, property, and history. The Zionist movement, which, starting roughly a half century prior to the establishment of the state of Israel, set out to establish a Jewish-majority state in a Palestinian Arab-majority space, succeeded—through force—in flipping the demographics of the territory, even though the Jewish population of Palestine had never been more than a third of the total prior to this point. While the military conquest operations may have begun in 1948, the groundwork for them was laid in the preceding decades.

In the decades before 1948, the Zionist movement built footholds throughout Palestine through colonization. While the various operations to purchase land in Palestine only succeeded in purchasing about 7 percent of the land of Palestine by 1948, Jewish colonies were scattered across the map, and would later afford the Zionist militias bases from which to create territorial contiguity after driving Palestinians out of the way. During this time as well, the Zionists amassed resources in the form of funds, arms, training, and institutions that would continue to power the effort to take over the territory. Key Zionist militia members, who would end up playing major roles in the Israeli military after the formation of the state, participated alongside British troops during the repression of the 1936–1939 Great Revolt. During this repression, important Palestinian leaders and resistance figures were either imprisoned or killed, leaving the society without much leadership on the eve of the ethnic cleansing. Vast intelligence gathering was also undertaken by the Zionists, and the Zionist militias ultimately had at their disposal dossiers on hundreds of Palestinian villages.

The patterns of the Nakba process as it has developed over decades makes it possible to identify likely targets in the next stages of this process.

While most areas of Palestine were affected by Israeli conquest operations in 1948, the most vulnerable were population centers that geographically presented a challenge to Israeli military objectives and Jewish demographic contiguity. The forced expulsion of tens of thousands of Palestinians from the towns of Lydda and Ramleh in July of 1948 is a prime example of this. Because these major population centers were located right along the road that connected Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, Israeli military leaders decided to eliminate them.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem in 1967 opened additional parts of Palestine to the Nakba process. Israel’s military conquest of these territories led some 250,000 to 300,000 Palestinians to seek refuge. Some of these refugees had already been made homeless in 1948, and were once again forced to flee. The 1948 and 1967 wars represent major depopulation events. In the years since 1967, the Jordan Valley in the West Bank has seen a major decrease in population as Palestinians have been forced from the area due to Israeli policy. Some 300,000 Palestinians lived throughout the expansive valley before 1967, but following the occupation and the closure of most of the land by the military and the usurpation of much of the rest of it for settlement building and expansion, only about 65,000 Palestinians remain in the isolated villages of the West Bank’s Jordan Valley.

Areas in the Crosshairs

The patterns of the Nakba process as it has developed over decades makes it possible to identify likely targets in the next stages of this process as the Zionist project in Palestine continues to unfold. Consistent patterns of replacement, depopulation, and the targeting of geographically sensitive areas help to narrow down some specific localities that will likely come under intensifying pressure in the months and years to come.

Jerusalem: Jerusalem has been in the crosshairs of the Zionist project for decades. The war of 1967 led to the occupation of the eastern half of the municipality and then the expansion of its municipal borders from 6.5 km2 to nearly 71 km2. This expansion incorporated into the municipal boundaries large swaths of land from the West Bank, including its Jerusalem and Bethlehem districts. Soon after 1967, Israel began aggressively building and expanding settlements around the Old City in an effort to create a ring of Jewish demographic contiguity around it and to separate it from the West Bank. Pockets of Palestinian existence in between these settlements have come under immense pressure. These include towns and villages like Kufr Aqab, Beit Hanina, Shu’fat Refugee Camp, Al-Ram, Sheikh Jarrah, Silwan, Beit Safafa, Sur Baher, Beit Jala, and al-Walaja, among others. A variety of measures are used to pressure Palestinians in these localities, including but not limited to direct intimidation and attacks, home demolitions, home expulsions, residency revocations, and the infrastructure of apartheid, such as the separation wall that cuts through the land of several of these locales, including al-Walaja, Shu’fat, and Kufr Aqab. Jerusalem will continue to be a focal point of the Nakba process in the years to come.

Khan al-Ahmar: This area, in which Palestinian Bedouin communities reside, is strategic for the Zionist project because its land connects the outskirts of the built-up area around Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley. Laying claim to this area and building in it would allow for Jewish demographic continuity that would bisect the West Bank. Bezalel Smotrich, the Israeli finance minister who has been handed unprecedented control over Palestinian life in the West Bank in recent months, admitted recently that the focus on Khan al-Ahmar has nothing to do with the legality of the community, but rather with the fact that it “sits in a strategic space…that will determine if, heaven forbid, there will be an Arab territorial continuum connecting Bethlehem with Nablus and Ramallah. That’s why we’re investing in this space now, and that’s why Khan al-Ahmar will be evacuated.” The Israeli government is holding off on the demolitions for now because of the diplomatic crises this action is likely to spark; but it has made it clear that carrying out the demolitions is a matter of when, not if. Once the right conditions present themselves, the Israeli government is likely to pounce on Khan al-Ahmar.

Masafer Yatta: About 20 miles south of Khan al-Ahmar, on the very southern end of the West Bank and lying up against the 1949 armistice line, or green line, which demarcates the territory, this collection of Palestinian communities lives surrounded by Israeli settlements. The military declared their territory a firing zone and compelled the residents to move, but after a string of legal battles they have thus far been able to stay on their land. However, the Israeli court determined in the beginning of this year that the state can force the residents out, and so the area now faces imminent expulsion.

Huwwara: In the north of the West Bank and just at the south entry to the Palestinian city of Nablus lies the village of Huwwara, which is in a particularly vulnerable position as it is surrounded by violent religious-nationalist Israeli settlements, which have a long history of carrying out attacks against adjacent Palestinian villages. Additionally, the village straddles a road that is accessed by Palestinians and Israelis alike, meaning that the settlers enjoy quick and regular access to the village. This spring, Israeli settlers carried out a destructive rampage against Huwwara, setting scores of cars and structures on fire and triggering shocked reactions from around the globe. From their own government, however, the Israeli settlers received words of support, at least from Finance Minister Smotrich, who said that the state of Israel should “wipe out” the village of Huwwara. The wiping out of Palestinian villages by the Israeli state is the most common practice in the Nakba, and Israeli government officials are speaking more openly about these intentions than ever before.

Area C: In addition to the specific localities mentioned above, dozens more in Area C of the West Bank are vulnerable, and are the likely next set of targets in the Nakba process. Area C makes up nearly 60 percent of the West Bank and is under exclusive Israeli security control and administration. Palestinians who live there are subject to various forms of coercive measures to push them off their land. These measures include closed military zones, attacks from Israeli settlers, and the denial of access to critical infrastructure and utilities, all of which serve to make life there as difficult as possible for Palestinians. Israeli settlements in this area enjoy unfettered access to everything they need, but neighboring Palestinian communities are deliberately and routinely denied freedom of access and free movement. Another form of threat facing these communities is right-wing legal activists who are using the Israeli legal system to press the state to accelerate Palestinian home demolitions. This was the case in Masafer Yatta and in many other areas. One right-wing legal activist group, Regavim, is targeting Palestinian communities across Area C, and is especially empowered today now that its founder, Minister Smotrich, is in charge of many of these decisions in the Israeli government.

Can Large-Scale Displacement Happen Again?

What separates the ethnic cleansing of 1948 from the ethnic cleansing of, for example, a small set of Palestinian hamlets in Area C is not essence, but scale. The question must therefore be asked: Is it possible that large-scale depopulation events like those of 1967 or even 1948 could happen again?

The wiping out of Palestinian villages by the Israeli state is the most common practice in the Nakba, and Israeli government officials are speaking more openly about these intentions than ever before.

Prior to 1948, Palestinian Arabs comprised the vast majority of the inhabitants of Palestine. Their existence on the land stood in the way of the Zionist project. It was simply not possible to put a Jewish majority state in a space where Palestinian Arabs outnumbered Jews by a ratio of roughly two to one. Only by forcibly altering the demographics could this happen. But does the Zionist project need another large-scale depopulation to move forward in Palestine? Some appear to believe so, and calls for mass violence and the displacement of Palestinians are increasingly prevalent in Israeli discourse as the country continues to shift to the right. Voices like Smotrich’s that call for wiping out villages and make clear that Palestinian communities physically stand in the way of Zionist ambitions are important indicators of what could be possible. And indeed, in a recent article, Michael Barnett, a scholar of the Rwandan Genocide who also studies the Middle East, considers the question of whether Israel is on the precipice of genocide. Looking at the United Nations’ report on atrocity crimes, he writes that out of the eight common and six specific risk factors for genocide, “Israel ticks all the boxes.”

The Zionist project in Palestine continues to grind on via the process of the Nakba, whether in small-scale episodes or in larger ones. What is certain is that the larger-scale episodes have taken place during larger, paradigm-shifting conflicts like the wars of 1948 and 1967. The fog of war has often provided cover for unspeakable crimes at significant scales throughout history. Given everything we know about the history of the Nakba process and about the ideologies driving the Zionist project today, it is not at all impossible that a large-scale conflict could once again become an opportunity for further mass displacement. However, even without this, the slow grind of the Nakba process produces daily impacts as the State of Israel entrenches its presence throughout the land of Palestine.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock/Rafael Ben-Ari