Two essential communities that are part of the ethnic makeup of Syria’s northern region, the Arabs and the Kurds, are now having to maneuver among many competing players. Turkey is on a march to curb Kurdish aspirations in the region, as the United States tries to fulfill its commitment to its Kurdish allies and the Syrian regime plots to reestablish its control. The latest developments in the field signal a clear threat of rising Arab-Kurdish tensions that could boil over if local, regional, and international players do not find a workable formula for de-escalation.

The first and foremost factor that drives ethnic tensions is competition over resources in the area. Second, the structure of the US-supported Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) suffers from Arab resentment of the Kurdish command chain as well as the indoctrination of the forces in PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) ideology. Third, given conflicting messages from Washington, uncertainties about the US role spur local parties to maximize their leverage before the departure of American troops. Of particular importance is the failure of economic restructuring and of the establishment of good governance in the liberated areas such as Manbij and Raqqa. Further, unless a satisfactory financial package is offered to assuage local needs, the clock is ticking against the US-led coalition to defeat the Islamic State (IS).

Latest Field Developments

A key question for Washington is how to maintain the Kurdish-Arab alliance in the absence of a front line against IS.

President Trump’s surprising statement regarding pulling US troops out of Syria and his freeze of $200 million in US funds for recovery efforts invited many questions about Washington’s long-term plans in northern Syria. In an apparent conflict with the White House, the Pentagon sent additional forces to protect Manbij in the wake of Turkish threats of a military operation. Emboldened by the Afrin victory, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared his intention to clear out the People’s Protection Units (YPG) not only from Manbij but also from the eastern Euphrates and up to the Iraqi border. Turkey’s concerns about Manbij go back to the summer of 2016, when the Obama Administration promised that YPG fighters would be withdrawn to the eastern Euphrates as soon as the city was captured from IS. On the Iraqi front, as it fights against Kurdish militants, the Turkish military has recently seized 30 villages by invading 10 kilometers deep into northern Iraq. Angering Ankara and further complicating US-Turkey negotiations, French President Emmanuel Macron met with Syrian Kurdish officials and expressed his eagerness to defend the coalition’s security architecture in Manbij.

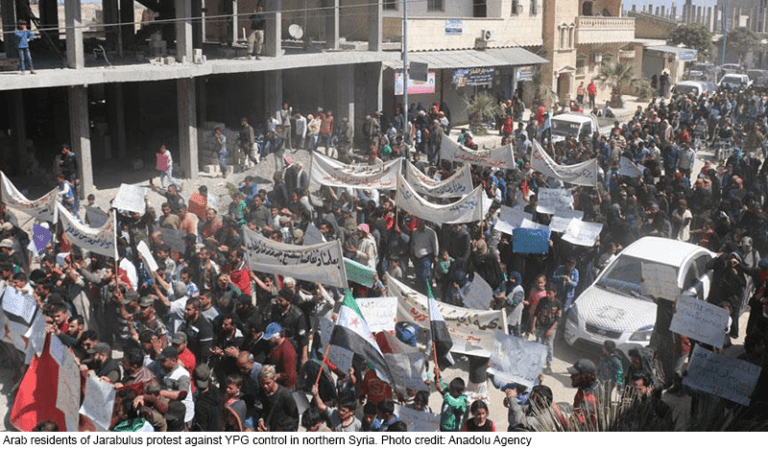

A key question for Washington is how to maintain the Kurdish-Arab alliance in the absence of a front line against IS, which, for all intents and purposes, has been defeated in much of northern Syria. In the past few months, the Manbij region has witnessed mass protests of local Arabs against YPG rule, and not surprisingly, Turkey has supported such demands. Syrian Kurds accuse Turkey of supporting Harakat al-Qiyam, a local Arab armed organization established in August 2017 to resist the coalition-led SDF. The group conducted assassination attacks and, most recently, targeted Shervan Derwish, the spokesperson of the Manbij Military Council (MMC). In addition, several tribal figures supporting the Assad regime were injured following a public protest in Manbij. Aware of tensions and to placate Turkey’s demands, coalition officials changed their description of MMC “as a primarily Arab force” in public statements, replacing the earlier depiction of “a mixed Arab and Kurdish council.” Unless there are structural changes to alter the YPG’s control over the MMC through the command chain, however, Arab subordination to Kurdish leadership will pose challenges to stability in the region. The mysterious assassination of Omar Alloush, a key figure for reconciliation between Kurds and Arab tribes who served as a member of the Raqqa Civilian Council, is the latest example of targeted killings that seek to exploit ethnic tensions.

The Puzzle of Resource Sharing

The SDF currently has sway over 30 percent of Syrian territory in the north. Despite its heavily Kurdish leadership, the SDF is poised to rule over the Arab majority in the near future. In the Kurdish cantons of the eastern Euphrates, Kurds constitute only a slim majority of 55 percent—a stark contrast with the Afrin region, where up to 95 percent of the population was Kurdish until the Turkish military incursion. Ethnic tensions mattered less when there was a strong coalition between Kurds and Arabs against the Islamic State; some Arab tribes sought revenge against IS, while others have long been allied with the Assad regime. The post-IS era, however, has unleashed ethnic competition over local resources.

Among potential causes that drive tensions are the oil fields. Kurdish cantons—collectively called Rojava (Western Kurdistan) by Syrian Kurds—include key oil fields in southern Hasaka. The al-Shaddadi oil fields, for example, are located in predominantly Arab lands and they are deemed especially valuable for Rojava’s economic future. Before the Syrian war, Hasaka and Raqqa provided almost two-thirds of Syria’s total oil extraction—251,000 out of 387,000 barrels per day.

The first and foremost factor that drives ethnic tensions between Syria’s Arabs and Kurds is competition over resources.

Oil revenue is already significant for Rojava and will be a major source of income if Kurds can initiate transactions with Damascus via the original pipeline. Negotiations with the regime, however, may not ease Kurdish-Arab tensions as some of the local tribes have long supported Damascus. In fact, during the 2004 Kurdish uprising in Qamishli, the Assad regime offered armed support to Arab tribes in Jazira—namely Adwan, Jabbour, Ougaidat, and Tay—to quell the riots. Despite the somewhat cordial relations between Damascus and the Kurds during the civil war, the Assad regime aimed to keep close relations with these Arab tribes. When Kurds began offering higher salaries to Arab locals after the SDF captured lucrative oil fields, the regime did not hesitate to conduct air bombings of the city of Hasaka in August 2016 to defend its public image as the arbiter of Kurds and Arabs.

In addition to oil, fertile agricultural land in the Jazira and Hasaka region may cause mayhem if Kurdish authorities choose to redistribute land to attract thousands of landless peasants. Before the civil war, the region produced 43 percent of Syria’s grains as well as 80 percent of its cotton. Although the region is considered Syria’s food basket, the Assad regime did not invest in it when farmers faced severe water scarcity in the past two decades. Years of drought and increasing consumption of water on the Turkish side have pressured the farmers whose traditional agricultural practices, such as gravity feed systems, demand extremely high-water usage. The regime promised to develop modernized irrigation techniques following the 2004 Kurdish revolt, but this was never implemented. According to Fabrice Balanche’s research, based on French Ministry of Agriculture statistics, the Hasaka province witnessed a 25 percent decrease in cultivated areas between 1995 and 2008, which caused a steady mass migration to urban centers in Aleppo and Damascus. The regime’s food and fuel policies—extracting maximum resources while deliberately not establishing industries—were consistent over the years, making the region subservient to the state.

It is unclear how redistribution of land under the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM)––an offshoot of the PKK––will be perceived by the local population. As the political coalition for administration of Rojava, TEV-DEM believes in a communal system of government that provides food and fuel security and education through local councils. The communes take care of most functions of a modern state; in many ways, local autonomy in Rojava appears to constitute a type of socialist revolution. Some local residents, however, began to raise concerns, complaining about the decision-making authority and unaccountability of the People’s Houses of TEV-DEM, which allegedly used the facade of local communes as a cover. There is also criticism of TEV-DEM’s strict budgetary control over the communes and its channeling of funds and humanitarian aid in exchange for recipients’ obedience to its authority. For dissident Kurds, it may be a failure of the PKK ideology; however, for dissident Arabs, such conditions are also seen through an ethnic lens, that is, the failure of Kurdish rule.

What is at Stake for Coalition Forces?

The March 30 Manbij ambush that killed American and British soldiers revealed the challenges that the US-led coalition faces in the post-IS era. Washington took a positive step in supporting Arab local representation by helping to establish a new political party, the Future Syria Party, to shape Raqqa’s future. Thus, the SDF forces’ political body will no longer be represented by the PYD flag; instead, the new party will be multiethnic with its motto, “democratic, pluralistic, decentralized Syria.” Turkish officials, however, were quick to express their cynicism—they perceived it as yet another PKK-led organization with a new brand name.

Without a restructuring of the SDF command chain, Washington’s current efforts may fail. Pentagon officials repeatedly highlighted their efforts to increase the number of Arab fighters in SDF ranks, and this was due to a number of factors—which included the fact that some locals had no other reasonable option to make a living except to join IS. The coalition also accepted pro-Assad loyalists into SDF ranks to boost Arab enlistment in the past two years. Now, as the fight against IS is over, regime supporters are particularly concerned about Kurdish leadership. What is often disregarded in media accounts is the minuscule number of the SDF’s Arab commanders. The fact that Arabs are not represented at the officer level is reminiscent of the Assad regime’s Syrian Army structure in which Sunni Arabs were fighting under Alawi commanders.

Uncertainties about the US role spur local parties to maximize their leverage before the departure of American troops.

The Kurdish dominance of the SDF at the commander level is furthered by the overt ideological training of Arab forces. For example, in a recent graduation ceremony of 140 Arab fighters joining SDF, after 45 days of training, pro-PKK slogans such as “No Life without Our Leader!” were chanted as a pledge of allegiance. The PKK’s ideology may sound attractive to anti-establishment Arab youth who are alienated from their tribes; however, the ideology is particularly alluring to Kurdish youth due to its Kurdish nationalist flavor, which does not resonate with Arabs. Moreover, the Arab tribes’ fear of Kurdish irredentism will be reinforced as long as the SDF structure enables indoctrination of PKK ideology. The Syrian regime’s “Arabization” policies since the 1970s have changed the demographics of the region; therefore, the Arab tribes’ anxiety regarding “re-Kurdification” of Rojava under TEV-DEM rule is not baseless. The YPG’s earlier practice of forced conscription of Arab boys and girls (under the age of 18) is still fresh in the memories of local Arabs.

Uncertainties Aggravate Ethnic Tensions

The Trump Administration’s conflicting messages about the future US role is a separate problem from the lack of American long-term strategy in Syria. On the one hand, the administration insisted on continued US efforts in eastern Syria to push back Iran until reaching a negotiation between Washington and Damascus. On the other hand, the administration does not appear to be interested in investing in reconstruction efforts to stabilize the territories liberated from IS—best summarized in Trump’s words, “let the other people take care of it.” The countering-Iran argument finds strong support among American military officials, who perceive the coalition’s control over resource-rich eastern Syria as potentially providing strategic leverage over both Damascus and Tehran.

Not surprisingly, ambiguity invites ethnic competition to prepare for the day American troops leave Syria. The Turkey-backed Free Syrian Army’s preemptive war against Kurdish fighters is a reflection of such competition. Arab residents of Manbij still suffer from a devastated economy, lack of public services, and power shortages 19 months after the city’s liberation from IS. As Balanche observes, Raqqa’s Arab majority residents may experience similar frustrations soon, as they expect massive western aid after liberation—assistance that seems to be a mirage, given the White House’s standpoint. If such a trend persists, the winner is not only jihadist propaganda about “western plunder” but also the Assad regime, whose sphere of influence has included relatively better public services. Turkey’s pro-government media also brags about Turkish investments in Azaz, most recently opening branches of PTT (the Turkish Postal Service) for cargo and the banking needs of the local populace, with the stated aim: “to ensure Azaz becomes an example city for the rest of Syria.”

The widening divide along ethnic lines poses a great danger for post-IS governance in northern Syria, which has relied on a US-led strong security architecture that binds Kurds and Arabs under the SDF flag. Unless addressed properly, such ethnic strife may have repercussions on the Iraqi side of the border as well. Washington’s current ambivalence only worsens the already brewing local tensions.