By 2015, over four million Syrians had fled the country’s civil war and arrived in neighboring countries, in Europe, and beyond. Today, the number of displaced Syrians abroad stands at 5.7 million, with an additional 6.9 million internally displaced people. Syrians fleeing the country have faced backlash almost everywhere they have gone, including from the residents of their host countries. And in the past few years, several governments have initiated efforts to repatriate them. A March 2021 survey found that although 70 percent of Syrians abroad hoped to one day return to their homes in Syria, very few—only 2.4 percent of respondents—expected to do so within a year’s time. A likely reason for this position is the fact that although Syrians often face xenophobia and high levels of poverty in host countries, life in Syria would represent a far greater danger and difficulty at this time.

Because the Syrian conflict remains subject to unpredictable developments, the country is far from ready to welcome home the millions of displaced people now scattered across the globe. Upon their return, Syrians would be greeted by an economy in shambles, an unstable security situation, and by possible retribution from the Assad regime. The whole of Syria will certainly not be prepared to accept large-scale repatriation until there is a stable political solution to the conflict. Until then, the United States can help move the needle toward establishing a government that meets a basic threshold for voluntary returns—and it should start where it has influence, in the Kurdish-held northeast. The Biden administration should push beyond its current policy of pouring humanitarian aid into the region and instead commit to supporting rebuilding and development efforts wherever possible, while also condemning premature efforts to repatriate the displaced.

Premature Repatriation

The issue of displaced Syrians living outside of the country is certainly complex, in part because these people are variously referred to as “refugees,” “migrants,” and “asylum seekers,” depending on how many resources their host countries wish to provide them. However, regardless of what they choose to call them, host countries are expected and required to provide protection and shelter to displaced Syrians according to the 1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Several countries where significant opposition to the presence of displaced Syrians exists have initiated or announced plans to begin repatriating them. Denmark, for example, drew widespread condemnation when, in 2019, the country’s foreign minister declared Damascus to be safe, began to review the status of 1,200 Syrians residing in Denmark, and stripped 69 of them of their legal residence status.

Host countries are expected and required to provide protection and shelter to displaced Syrians according to the 1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Meanwhile, in June 2021, Turkey announced its own plan to begin large-scale repatriation to northwest Syria. And in July 2022, despite there having been no real change in the security situation in Syria, Lebanese caretaker Minister of the Displaced Issam Charafeddine announced a plan to not just review individual cases, but to return all of Lebanon’s 1.5 million displaced Syrians to regime-controlled territory. Both Turkey and Lebanon are in the midst of economic crises and Syrians have experienced some of their worst effects. But even though the vast majority of Syrians in Lebanon and Turkey live in poverty, most say they are still better off staying where they are than risking returning to Syria.

The truth is that the whole of Syria is unsafe for large-scale repatriation. But the level of danger varies among the country’s three main areas of control: territory held by Bashar al-Assad’s regime, areas in the Turkish-influenced northwest, and territory under the control of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), which is run by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces. Denmark and Lebanon have either sent or plan to send Syrians to regime territory. And although the Assad regime is advertising its territory as safe enough for repatriation, it is easy to suspect that its motive is to benefit not only from additional aid money that would come along with returnees, but from the legitimacy that their presence would offer the regime as well.

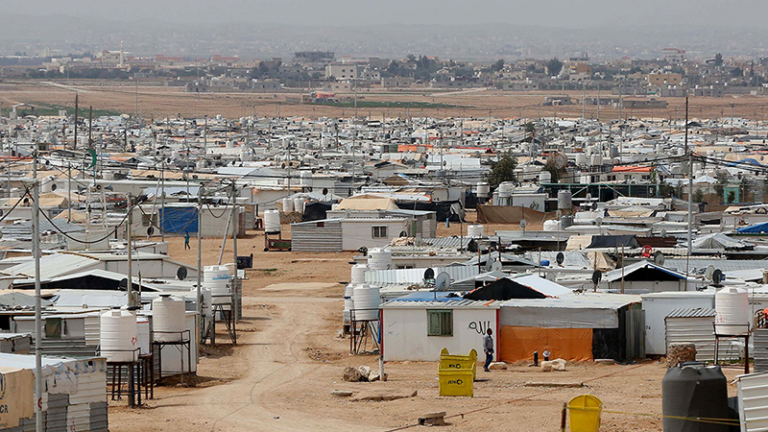

A lack of habitable infrastructure, safety, and access to employment, as well as the possibility of facing regime abuse are among the top factors keeping Syrians away. In addition, the Assad regime has seized the homes of those who left, leaving them little to return to.

A lack of habitable infrastructure, safety, and access to employment, as well as the possibility of facing regime abuse are among the top factors keeping Syrians away. In addition, the Assad regime has seized the homes of those who left, leaving them little to return to. When Syrians who returned were asked about their experiences after doing so, 41 percent of respondents said that they did not return voluntarily, and 11 percent complained of facing or seeing loved ones face physical violence and harm. Even when returnees have been able to reclaim their property, they have risked becoming subject to torture, arbitrary arrest, and unlawful detention. Negotiations between Beirut and Damascus on repatriation reportedly included discussions on allowing dissidents to agree not to engage in action against the Assad regime in exchange for their safety, although few believe that they will be exempt from the regime’s abuses.

The Turkish-influenced northwest is hardly any safer. The Turkish government, in coordination and cooperation with the opposition Syrian Interim Government, is taking steps to improve the humanitarian situation and improve access to housing and infrastructure for one million returnees. However, few observers expect Turkey to be able to find one million Syrians who will willingly fill these homes. More importantly, the Turkish government is interested in pursuing its war against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and its Syrian offshoot, the People’s Protection Units, thus making the region too unstable for repatriation. Despite a surging backlash in Turkey against displaced Syrians, and despite the challenge posed by Turkey’s current economic crisis, most Syrians would still prefer to continue living their lives in Turkey rather than put their faith in the fragile situation in Syria.

The AANES, meanwhile, remains a long way from achieving the stability and governance necessary for returnees. The risk of conflict breaking out is perhaps highest in the northeast, with threats stemming from Turkey’s incursions into AANES territory and an increase in activity by the so-called Islamic State and other militant groups. Kurdish rule over a Sunni Arab majority also provides outside actors with ample opportunity to stoke tensions. But despite the threat of conflict, the AANES leadership’s inability to restore jobs, healthcare, education, and utilities is the leading factor preventing returns—much as it is in areas of Syria dominated by Turkey and the Assad regime.

Faltering US Policy

While the United Nations and other international organizations have been working in regime-controlled Syria, the United States has been focused on contributing humanitarian aid, primarily in the northeast. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the State Department have touted the fact that the US is the largest donor of humanitarian aid to Syria, but the strategy of pouring money into humanitarian assistance has not been enough. If the United States were willing to become more politically active in the country, it would have a good chance of playing a positive role in supporting social and economic recovery for future returnees. US policy can have an impact if it focuses on promoting good governance that fosters development and the delivery of basic services. Without such developments, the resettlement of internally displaced people and the return of those abroad will remain out of reach.

The START-Forward program is a joint State Department–USAID stabilization initiative established to help authorities in the northeast “peaceably manage conflict and prevent a resurgence in violence.” Primary methods of achieving this goal include supporting the delivery of key basic services and economic development. However, US stabilization efforts in northeast Syria have faced numerous obstacles. Since the UN’s work is limited to what the Assad regime allows under its control, USAID and the State Department have few options for partners on the ground. And making matters more difficult, most of the region’s skilled local staff left when the area was under IS occupation. But the main reason that US stabilization efforts have failed is the inconsistency of the START-Forward program. The risk of conflict and militant activity has surged and receded over the years, and the program has fluctuated along with it. The US is the AANES’ main partner, and without a more consistent and concerted investment in civilian engagement, the region will lose momentum in preparing for recovery and development.

The US is the Kurdish region’s main partner, and without a more consistent and concerted investment in civilian engagement, the region will lose momentum in preparing for recovery and development.

If Syrians abroad do not see a future for their children in Syria, returning will never become a possibility. A case in point is US investment in the education system, which is a key pillar of efforts to rehabilitate the social infrastructure of the region. American funds went into rebuilding schools, although US officials neglected to ensure that the curriculum was accredited, and failed to address serious issues regarding teacher quality. The State Department and USAID could and should provide resources and expertise to address these failures and shortfalls.

The Road to Repatriation

In order for the whole of Syria to become ready to accept large-scale repatriation, there first needs to be a political solution for the current fragmentation of the country after years of war. That solution, however, is a long way off. In the meantime, the United States should commit to the START-Forward program and to humanitarian initiatives that help both the Syrian Interim Government and the government of the AANES to provide the services that residents require. USAID and the State Department should work together to make sure that water, power, healthcare, and education are all accessible, while also taking the extra step to make sure that these systems can one day be integrated with the rest of the country.

These measures will help prepare Syria for a future where Syrians abroad can begin to see a safe and prosperous life awaiting them at home. But if Syrians were forced to return to any part of Syria today, they would likely face conflict, instability, and greater poverty than they do in their current host countries. Importantly, they will also face the very same authoritarian Assad regime that was instrumental in causing their displacement in the first place. The Biden administration must therefore strongly condemn efforts to repatriate Syrians before benchmarks for protection are met, and should continue to contribute humanitarian aid to states hosting Syrians who fled the country.

The Biden administration must strongly condemn efforts to repatriate Syrians before benchmarks for protection are met, and should continue to contribute humanitarian aid to states hosting Syrians who fled the country.

The international community can also help bring about the development of a Syria where human rights and the rule of law are respected, where displacement and conflict are not daily concerns, and where families can raise children with the expectation that they will have access to education and a means of living. Achieving this goal will require both a major diplomatic effort and continued humanitarian and development assistance. The recent trend of carelessly repatriating Syrians, however, does nothing but violate human rights and place innocent people in danger.