President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and his administration’s decision to move the American embassy there have probably thrown all US caution to the wind regarding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The president is also said to be preparing to propose a peace plan that he claims will lead to an “ultimate deal” in the Middle East. Further, his decisions have helped to increase pressure on the Palestinian leadership to address what everyone knows is a very challenging and disadvantageous status quo vis-à-vis Israel and its creeping colonization of occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank and continued siege of the Gaza Strip. Addressing the United Nations Security Council on February 20, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas proposed an international conference that would work on a resolution to the conflict based on the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002, which called for a Palestinian state along the pre-June 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.

To help shed light on the complications of President Trump’s announcements, the Palestinian leadership’s potential choices, and future possibilities, Dr. Imad Harb, Director of Research and Analysis at Arab Center Washington DC (ACW), asked ACW Executive Director Khalil Jahshan to comment on several related issues. His answers are below.

Imad Harb: Where does the Palestinian leadership stand today after the United States, the main sponsor of the Middle East “peace process,” recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and allegedly took the issue off the bargaining table?

Palestinian leaders felt quite betrayed and confused by the unpredictability of the American administration.

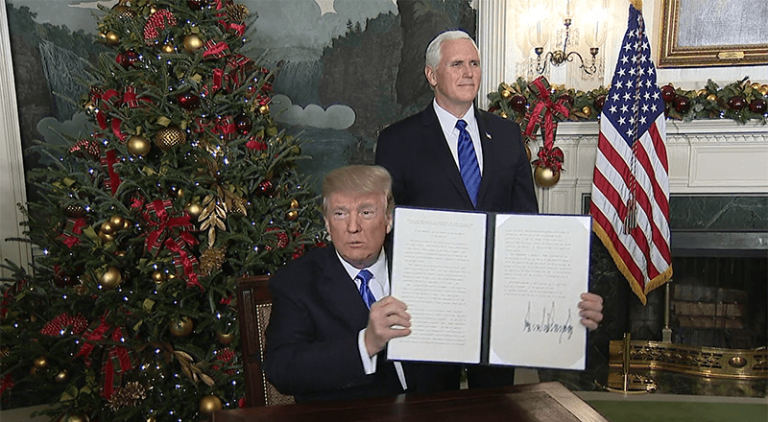

Khalil Jahshan: The decision by President Donald Trump on December 6, 2017, to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and move the US embassy there was a severe shock to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and his trusted aides. The shock was both personal and political—a fact whose psychological impact and political magnitude the White House still fails to understand. Abbas was personally convinced that Trump’s promises were admittedly nonconventional but genuine, and that no surprising decision such as this one would be forthcoming in Washington. On the contrary, his four personal interactions with the president and those of his key advisors, particularly the meetings held in Washington and New York in 2017, left him with the overly optimistic impression that the Trump Administration seemed serious about its intentions to launch a new negotiations process in the Middle East that might not be totally to the Palestinians’ liking, but nonetheless, serious enough to warrant an honest consideration by the PLO.

The United States’ ill-timed and ill-advised change in policy left the Palestinian leadership demoralized, feeling betrayed, and lacking the political credibility to proceed with any significant initiative. It became quite clear for those of us who have dealt with the Palestinian leadership before and after the Jerusalem decision that their self-confidence and trust in Washington vanished and their willingness to move forward with any new peace plan was totally transformed. Despite the bravado they displayed in public at home or abroad, they nonetheless felt quite betrayed and confused by the unpredictability of the American administration.

As a result, the Palestinian leadership today stands isolated, with its credibility diminished and political maneuverability to lead its people quite compromised. In front of their constituents, these Palestinian leaders feel humiliated by their potential peace partner in Washington who stabbed them in the back without any warning or convincing explanation.

IH: By extension, how does the Jerusalem decision influence the long-promised “ultimate deal” by President Trump?

KJ: By December 7, 2017, the “ultimate deal” promised by Trump was transformed overnight into the “ultimate slap in the face.” The Palestinians were clearly the immediate losers in this diplomatic blunder. However, they were not the only losers. In the long term, the United States and Israel also stand to lose a great deal because the shift in policy by the Trump White House diminished, in practice, the prospects of peace in the Middle East that successive US administrations have pursued over the past seven decades as a central US national security objective in the region.

In my humble judgment, the Jerusalem decision was not taken in a political vacuum. It is the direct outcome of certain characteristics inherent in the Trump Administration’s mindset and modus operandi. First, compared to its recent predecessors, this administration is one of the least experienced in foreign policy and national security matters. It chose to declare its intention to embark on a peace initiative in the Middle East without any serious groundwork whatsoever. Armed with his limitless arrogance and big ego, President Trump thought he could succeed where others before him failed. He never stopped referring to himself as a “great negotiator.” This inflated sense of achievement came back to haunt the president before he even revealed his “ultimate” plan.

Peace cannot be achieved without agreeing on Jerusalem.

Second, related to this unjustified arrogance is the disregard this president and his Middle East peace team hold toward conventional wisdom and diplomatic experience relevant to Arab-Israeli peacemaking. It is true that efforts to achieve peace in the region have failed for decades due to all kinds of objective and subjective reasons; nevertheless, that history produced a credible body of knowledge that cannot simply be dismissed or replaced. There is no reason to reinvent the wheel every time we elect a new leader in Washington—and in Tel Aviv or Ramallah, for that matter.

President Trump is not impressed by the fact that there have been more than 70 attempts at peacemaking in the Middle East since 1939. Although they failed to achieve the intended results, they taught us some fundamental lessons that are hard to ignore:

- No Mideast peace can be achieved without direct Palestinian participation.

- No peace is possible without allowing self-determination for the Palestinians.

- No peace is feasible without an agreement on Jerusalem.

- No peace will work without a just solution to the refugee problem.

Yet, Trump and his peace processors chose to prejudge the central issue of Jerusalem and somehow deluded themselves that the issue is now “off the table.” This disdain for international law and several decades of diplomatic agreements has in fact changed nothing about the status of Jerusalem, as illustrated by subsequent UN votes. Instead, this ill-conceived approach has simply disqualified the Trump Administration from pursuing its yet to be announced “ultimate deal.” To add insult to injury, the soon to be unveiled deal is promising more missteps regarding two crucial final status issues––the right of return and Palestinian sovereignty. The plan’s provisions on both items fail to meet the most minimal Palestinian aspirations.

IH: Do you think President Mahmoud Abbas’s proposal for an international drive for peace will be successful?

KJ: President Abbas is in a very tough bind and he knows it better than any of us. At this late stage in his long political career, Abbas feels that the current crisis with Washington will most probably determine his personal political legacy, and more significantly, the fate of the Palestine issue.

The Palestinian response to Trump’s change of policy on Jerusalem was somewhat assertive but predictable. In his address before the UN Security Council on February 20, 2018, Abbas reiterated the Palestinians’ steadfastness in working to end the Israeli occupation and pursue self-determination according to international law.

Abbas minced no words regarding Trump’s new policy on Jerusalem, which he characterized as “unlawful,” insisting that East Jerusalem is part of the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967 and is the capital of Palestine. He accused the American administration of contradicting itself and negating its own commitments regarding Jerusalem.

The core of the Palestinian response to Trump lies in the belated challenge to US hegemony over peacemaking in the Middle East. Abbas questioned the ability of Washington to solve the conflict without the establishment of “a multi-lateral international mechanism” in line with international law and relevant UN resolutions. In other words, US hegemony over peacemaking in the Middle East is no longer acceptable to the Palestinians. This does not exclude Washington from the process but denies it exclusivity in mediating the conflict—if and when negotiations resume.

I believe this demand by Abbas is legitimate and justified considering the United States’ flagrant and continued bias toward Israel. However, I am not optimistic that expanding the Middle East Quartet (which was established as a mechanism in 2002 and comprises the United Nations, the European Union, the United States, and Russia) or adding sponsors to a new negotiations process are feasible now, considering the unwillingness of European allies to challenge Washington or of other world powers to muscle their way into the process—which is unwanted by the United States and Israel.

IH: Considering the balance of forces and influences on the parties involved, as well as the amount of power each party can wield, how reasonable is Abbas’s call for implementing the Arab Peace Initiative (API) of 2002?

KJ: The Arab Peace Initiative proposed by former Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia at the 2002 Beirut Arab Summit was stillborn for two main reasons. First, the Arab countries that introduced and supported the concept failed to “market” it in advance to ensure its acceptance by Israel and its supporters. The Arab side did not understand the significance of the initiative and the historic magnitude of its provisions, and therefore underestimated the need, in advance, to secure Israeli compromises in return.

Second, Israel’s quick and unequivocal rejection of the initiative at the time nullified the offer and offset its political significance. Israel later softened its approach under former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and the late Prime Minister and President Shimon Peres. However, the initiative was never enthusiastically accepted nor officially reciprocated by Israel. By the time the Arab side recovered from its shock and tried to amend certain segments to make them more palatable to Israel, the API expired on the shelf.

With all due respect to President Abbas, calling for the implementation of the API today is not going to generate excitement in Israel, Washington, or even in Saudi Arabia, its original sponsor in 2002. I am afraid the expiration date on the Arab Peace Initiative has unfortunately come and gone.

IH: The intra-Palestinian political fracture is a defining factor in how things develop from here. Is there a chance that Palestinian factions will be able to compromise and create a unified position?

In the long term, the United States and Israel stand to lose a great deal.

KJ: In principle, I am supportive of Palestinian national unity, although I prefer the less ambitious term “national coordination.” In practice, however, I am not optimistic nor am I a fan of the reconciliation process as it unfolded in the past. The fitful process is continuing as we speak. As a matter of fact, there is currently an Egyptian security mediation group in Gaza trying to energize the process. In addition, a Palestinian Authority committee voted on February 27 in Ramallah to implement an earlier recommendation to send 3,000 police personnel to Gaza to assume responsibility for security in the Strip.

The problem lies in the lack of trust and goodwill between Fatah and Hamas to coexist in a functional democratic setting. I do not believe this is possible now: neither party is capable or willing to govern democratically while allowing the other to function freely as a loyal opposition party. Until we reach that level of political maturity, I am afraid national coordination will continue to elude the Palestinian people to the detriment of Palestinian national interest.

IH: Can, and will, domestic Israeli politics have impact on where things go from here? Can you speculate about Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s fate and possible replacement? Will that make a difference?

KJ: Many analysts in the Arab world, particularly in occupied Palestine, argue that there is little difference between right-wing and left-wing politics in Israel when it comes to Israeli policies vis-à-vis the Palestinians. These policy distinctions between both Israeli camps might be too subtle or sometimes too obscure to make a difference for Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, but they cannot be objectively denied or analytically dismissed despite their relative significance. As the de facto occupying power that dominates all economic, political, and social aspects of life in Palestine, Israel has a tremendous impact on current and future Palestinian politics.

As is widely known, Israel is currently going through a turbulent political juncture stemming from multiple bribery and corruption charges leveled at Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. He has faced similar charges in the past and managed to elude prosecution; this time, however, most Israeli analysts believe the charges against the prime minister to be too serious and the evidence quite overwhelming. Conventional wisdom in Israel holds that this time, “Mr. Teflon” will not be able to elude justice and cling on to power much longer. Israeli political scientist Yaron Ezrahi, for example, insists that Netanyahu’s “downfall is imminent.” Ezrahi speculates that Israel’s prime minister will have to resign or he will be toppled by “a rebellion from within” his own party (Likud) or the governing coalition. Of course, as we all know, in addition to his widely acknowledged competence in public relations, Bibi has been extremely skillful at making enemies, and currently, the contending chickens have come home to roost.

My guess is that Netanyahu will most probably be replaced by a fellow Likudnik or a center-right politician. I am sure that replacing Netanyahu by another Likud member will not make much of a difference for the Palestinians in their conflict with Israel. As a matter of fact, all potential Likud candidates—including Minister Naftali Bennett, former Knesset Member Gideon Sa’ar, Minister Yisrael Katz, and Minister Miri Regev—are ideologically as radical if not worse than Netanyahu, if one could imagine that. Center right contenders like former Ministers Yair Lapid and Moshe Kahlon, and Knesset Member Meir Cohen, might offer some minor policy nuances toward the conflict with the Palestinians, but they will not lead Israel on a significantly different path than that traveled by Netanyahu. Even if they desired to adopt a modified stance, their essentially radicalized constituents would not allow them to do so.

As for the Labor Party, it is currently suffering from the same political bankruptcy, internal divisions, and uninspiring leadership as the Democratic Party in the United States. Some leaders in Labor might be tempted to offer alternative policies to Netanyahu’s approach to the Palestinians; however, their chances of replacing Netanyahu or radically departing from his colonialist and expansionist policies are very limited indeed. Although those on the left flank of the party, like Knesset Members Shelly Yachimovitch, Amir Peretz, or even Isaac Herzog, might sound more appealing to the Palestinian side, others, like Labor Party Leader Avi Gabbay, are as palatable as Likud leaders.