The protests by millions of citizens across the Arab region in 2011 were about more than bread and a better standard of living. They emphasized “justice, democracy, and freedom,” all fundamental rights lacking for decades in the stagnant Arab political order. Freedom of expression and freedom of the press are two of these rights; but six years after the inception of the Arab uprisings, the harsh reality points to a decline in both.

The reversals occurring after the Arab Spring revolts have to do with the complex dynamics of the relationship between government and media, with the contemporary Arab media scene undergoing a number of important shifts. They also have to do with the pressing challenges that have been impacting the performance and professionalism of Arab media over many decades. These include factors such as the high illiteracy rates in most of the Arab world in addition to digital illiteracy, both of which limit the media’s circulation and reach. Another factor is the knowledge crisis, which refers to the various bureaucratic, administrative, and logistical barriers that hamper journalists’ ability to gather news and information. Professionally also, there is the lack of sufficient training for journalists. Finally, the regimes in power in most Arab countries impose certain restrictions on freedom of the press, which range from harsh measures, such as direct censorship, severe punishment, or even arrest and imprisonment, to softer measures, such as sponsorship, co-optation, and funding.

Overall, the picture emerging in many Arab countries has been that of a mostly loyal press that does not deviate from the policies dictated by the regimes and does not dare to oppose those in charge—with the unique exception of a few countries, such as Lebanon and Kuwait, which have been historically more liberal than the rest of the region when it comes to their media systems. The introduction of satellite television and the internet and the eruption of protests in the Arab street have not furthered freedom of the press in the Arab world.

Post-Arab Spring Press Freedom: Bad, Worse, and Worst

As the annual assessment of press freedom worldwide, the Freedom House report ranks countries on a scale of 0 to 100, with the freest ranked at 0 and the least free ranked at 100. The 2017 report highlighted the decline in press freedom in a number of post-Arab Spring countries. The country that fared worst in this category was Syria, which was included among the “worst of the worst” ten countries that had the least press freedom in the world, with a score of 90.

This was attributed to a myriad factors, including, but not limited to, the ongoing civil war in Syria with its atrocities and humanitarian crisis, contributing to a largely unsafe environment for journalists to perform their jobs. This, in addition to Islamic State (IS) insurgency operations and deadly terrorist attacks, forced many journalists to flee to neighboring countries, mostly Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. But without the needed accreditation and documentation, many of these journalists were unable to continue their work adequately and professionally.

Even in exile, some of the Syrian journalists were unsafe, as revealed by the horrific murder of Syrian activist Orouba Barakat and her daughter, journalist Halla Barakat, in their apartment in Istanbul. Although a relative confessed to the murder, many blamed President Bashar al-Assad’s government, since both of the slain women were vehemently opposed to and openly critical of the Syrian regime’s draconian policies.

Yemen is another highly unsafe country for journalists. According to the Freedom House report, “Yemen’s media environment has become increasingly polarized since the civil war began in 2015 as most journalists must align their reporting with one of the rival governments, stop working, or flee the country. At least six journalists were killed in Yemen during 2016, and at least nine were forcibly disappeared. In addition to the lethal dangers of working in a conflict zone, reporters had to contend with raids and arbitrary detentions by whichever de facto authority controlled a given area.”

To cite one example among many, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), “gunmen from the Ansar Allah movement, commonly known as the Houthis, on December 2 stormed the Sanaa headquarters of the television channel Yemen Today and detained the channel’s employees.” The committee cited a Reuters reporter in Sanaa as saying that at least three guards were hurt while gunmen held 40 employees inside their building. This, the committee contended, is indicative of the conditions in which journalists are forced to work in Yemen where institutional collapse allows impunity and fear.

In fact, both Syria and Yemen, along with Iraq, were included among “the world’s deadliest places for journalists” in the 2017 Freedom House report, due to ongoing conflicts and the continuous surge in violence and unrest in both countries. The CPJ also included them among the ten deadliest countries in the world for journalists, with Syria ranked second, after Iraq with 7 journalists killed in 2017, and Yemen ranked sixth with 2 journalists killed in the same year.

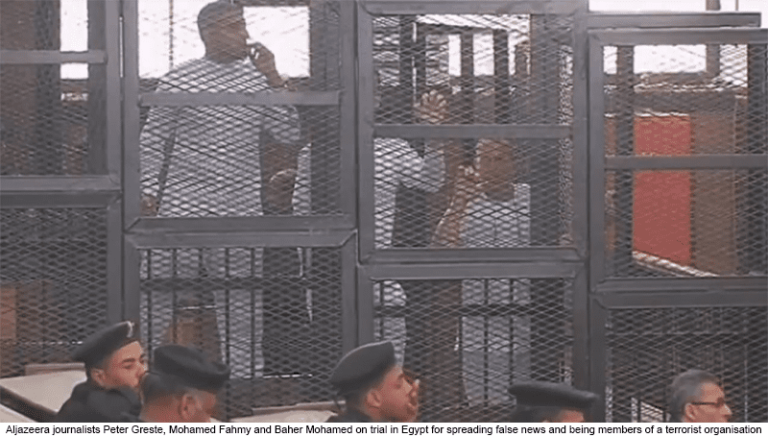

One of the countries witnessing a decline in the degree of media freedom in the 2017 report, compared to that of 2016, was Egypt, which was included under the category of “countries to watch.” This indicated that as the country’s security and economic crises intensify, so do the regime’s attempts to assert more direct control over private media to suppress criticism of the government’s performance.

According to the report, “Egyptian authorities restricted journalistic freedom in part through gag orders and censorship practices that suppressed criticism of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and other high-ranking officials. The military’s influence on news channels was apparent, with observers noting that the private media no longer had any level of independence, and organizations focused on protecting journalists’ rights faced legal prosecutions and harassment from security forces.”

This created a general atmosphere of fear and intimidation among media practitioners, whether in mainstream or private media outlets, in addition to independent activists and bloggers. One good example was the arrest and harsh sentencing to five years in prison for the young Egyptian blogger Alaa Abdel Fattah, who was part of the group known as “No Military Trials for Civilians.” According to Human Rights Watch, since President Mahmoud Morsi’s overthrow in 2013, the Egyptian authorities have “arrested or charged at least 60,000 people, forcibly disappeared hundreds for months at a time, handed down preliminary death sentences to hundreds more and sent 15,000 civilians to military courts.”

Another famous case that attracted international attention was the arrest of the Egyptian journalist and researcher who specialized in Sinai affairs, Ismail Alexandrani. Reporters Without Borders (RSF), which ranked Egypt 161st out of 180 countries worldwide in terms of press freedom in its 2017 World Press Freedom Index, called for the immediate release of Alexandrani, who has been held in pre-trial detention for two years, so far, without a legal trial or official charges.

Even Tunisia, which was hailed by many as the “cradle of the Arab Spring” and the only survivor of its tumultuous development, did not live up to its image of “exceptionalism” when it came to freedom of the press. According to the Freedom House 2017 report, “Tunisia’s attempts to build a stable democracy with a free press were hampered by ongoing security concerns, the president’s rhetorical attacks on the media, and a rise in police interference with journalists’ work, particularly in connection with protests. The media sector also suffered from a weak economy, with some media outlets forced to shut down and hundreds of journalists either laid off or obliged to work without regular payment.”

Recent incidents indicative of the tightening of the Tunisian government’s grip on the media, such as the creation of a regulatory body for audiovisual communication and the banning of a small daily publication, led a number of national and international organizations to voice concerns over freedom of the press in Tunisia. A group consisting of the Tunisian Press Syndicate, Reporters Without Borders, and Amnesty International sounded the alarm on World Press Freedom Day this year (May 3, 2017).

Similar concerns were previously voiced by a number of national and international organizations on World Press Freedom Day in 2015. They stated that the start of the year was characterized by an upsurge in abuses of freedom of the press in Tunisia, and they pointed out that the significant number of violent attacks against journalists and bloggers, together with the restrictions on freedom of expression and information provided in a number of draft bills of law, are of serious concern.

Cyberwars Present a New Phase (and Face) of Repression and Resistance

The introduction of the internet could best be seen as a double-edged sword for freedom of expression and of the press in the Arab region. On the one hand, it provided activists and private media outlets with an important platform for expressing their opinions. On the other hand, it gave the regimes in power an equally strong tool to curb and obstruct this activism and to silence dissent.

Cyberspace became an important battlefield for this new tug-of-war between regimes and their opponents, since controlling the internet became both the new phase as well as the “new face” of censorship as “governments developed new systems of information control and the technology that allows information to circulate was co-opted and used to stifle free expression.”

One country worth singling out in this regard is Syria, which, according to the 2017 Freedom House report, is “among the many staunchly autocratic countries where physical and online monitoring is a fact of life for journalists, intended in part to intimidate the media and suppress critical coverage.”

Leaders in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya were taken by surprise because they did not anticipate the new wave of cyberactivism that was coming at them and therefore were either unable to react to it, or reacted to it with failed strategies. The Syrian government, however, was carefully observing and building its own learning curve. For example, the Syrian regime learned from some of the tactics that had backfired and proved to be counterproductive, such as pulling the kill switch, which refers to shutting down the internet for a period of time. In addition, it learned from Egypt’s blocking of all mobile phone services in the midst of the 2011 revolution which instigated an even larger wave of protests and cost huge economic losses for the country.

Therefore, the Syrian regime developed a new strategy for combatting cyberactivism while minimizing potential damage, both politically and economically. It resorted to shutting down the internet only on Thursday evening and Friday, which is the weekend period in the Arab world when most people are likely to gather, march, and protest—to avoid the undesirable outcomes experienced in Egypt. This ushered in a new phase in the ongoing cyberwars between Arab regimes and their opponents, where the regimes in power—and not only the activists—are building their own learning curves and polishing their online skills and tools.

The Syrian regime also created its own “Syrian Electronic Army,” which refers to a group of highly trained and skilled hackers who claim to be independent but who are, in fact, working on behalf of the Syrian regime to block and sabotage opponents’ websites and to obstruct their online activism. These hackers were praised by Assad in one of his speeches for their patriotism and loyalty to their country—a gesture that was met with mockery and criticism by the regime’s opponents who simply consider this group’s acts a form of governmental spying and online piracy. Indeed, the Syrian government continues to rely heavily on internet surveillance and online monitoring to trace, sabotage, and hack the websites of dissidents, activists, and opponents on a regular basis, placing the country in second position, after China, as the “world’s worst abuser of internet freedom.”

One of the countries that witnessed a significant decline in the degree of internet freedom, according to the “Freedom on the Net” report issued by Freedom House in 2017, was Egypt, which scored 68 points on a scale of 100, recording a five-point decline since 2016. This was mainly attributed to the severe governmental crackdown on all forms of cyberactivism, resulting in blocking hundreds of websites, including that of the progressive and independent news site Mada Masr, as well as the websites of numerous local and international human rights organizations in addition to those of media outlets, such as Al Jazeera. The total number of blocked websites, according to this report, jumped to 434 by October 2017. Additionally, there was a surge in cases of arrest, sometimes resulting in harsh jail sentences, against those who expressed critical views of the government and its top officials.

Other “post-Arab Spring” countries were also not favorably rated in this same report due to very similar practices against opponents and critics, albeit in varying forms and to varying degrees. This has contributed to the overall backlash that is currently growing in this transitioning region, simultaneously in the mainstream media domain as well as in the online sphere.

The Overall Picture and the Road Ahead

The picture emerging from this discussion is that of a transitional and paradoxical yet highly challenged Arab media landscape, one that shapes, reflects, molds, and mirrors the equally complex, ambivalent, and challenging social and political landscape in this volatile and swiftly transforming region. Just like the path to democratization and reform has been obstructed or derailed in most of the countries witnessing the wave of uprisings since 2011, so has the path to media freedom, in a parallel, intertwined, and interconnected vicious cycle.

This has resulted in a mostly “elusive press freedom,” which is the byproduct of direct and indirect restrictions by ruling regimes; the result is a media environment in which journalists, both in mainstream and private media, as well as cyberactivists are practicing a considerable degree of self-censorship. This is mostly out of fear of facing criminal charges due to claims of defaming, insulting, and criticizing rulers and public officials, fabricating false information, or, even worse, supporting terrorism—which has become the most common charge against the opponents of Arab regimes today.

Moving forward, it is clear that the continuation of sectarian strife, political unrest, violence, and economic and social hardships in most of these countries will give birth to an increased level of governmental repression and curbing of human rights and basic freedoms, in general, and freedom of the press, in particular.

The intention and rationale of repressive regimes could very well be obstructing, or at least delaying, any new potential wave of uprising, protest, and revolt, as the political, economic, and social conditions of most of these countries continue to decline and deteriorate.

This leaves us with the big question as to why these governments are not building their learning curve in dealing with their citizens’ needs, demands, and grievances by creating new venues for reform, rather than solely building their learning curve in blocking dissent and silencing voices of opposition, both online and offline. After all, such policies did not prove to be effective in the past, as the uprisings of 2011 have taught us.