The US policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran often appears to be a strategy in search of an endgame: is it a change in Tehran’s behavior? A change in regime? Or a change in the diplomatic weather—a lightning stroke that enables a new dynamic, like the one that brought about the Kim Jung Un-Donald Trump summit in Singapore?

Nobody really knows, notwithstanding President Trumps’s announcement in Japan on May 27 that he does not seek regime change in Tehran. But as the uncertainty and confusion mount, so do the odds of a military confrontation that has put the whole region on edge. Nowhere is this tension felt more acutely than in Iraq, where the government has been placed in an almost impossible position as it tries to balance its need for friendly Washington ties with the importance of not upsetting its complicated economic and political relationship with Tehran. This tension—which began to simmer not long after the United States declared its intention to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal and begin reimposing sanctions—now threatens to do permanent damage to the US-Iraqi relationship, a cornerstone of the American position in the Middle East.

Threat to US Troops

When the United States announced on May 5 that it would send the USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group and a bomber task force to the Gulf in response to unspecified Iranian threats, speculation centered on where and how a possible confrontation between the United States and Iran might play out. Attention soon focused on Iraq. The 5,000 US troops currently stationed in the country, until quite recently de facto if uneasy allies with pro-Iranian Shia militias in the fight against the so-called Islamic State, would be a likely target for retaliation in case of a US strike on Iran, as militia leaders were quick to point out.

The 5,000 US troops currently stationed in the country would be a likely target for retaliation in case of a US strike on Iran.

“Americans are in trouble now, especially considering that US troops’ bases are known in Iraq and the region and can be targeted easily,” militia leader Moeen al-Kadhimi said. Laith al-Azari of the powerful pro-Iran militia Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq’s political bureau warned that any attempt by the United States to target Iran from Iraqi soil would be countered “with all possible means.” That possibility, which raises the alarming prospect of US retaliatory strikes on Iraqi soil, is of great concern to the government, which has reportedly been working to extract promises from militia leaders that they will not attack US forces, come what may. But it cannot control or influence them all. Nor can it control all the tools Iran has at its disposal—which are many—nor Iran itself.

A Long Time Coming

The latest tensions reflect the pressure that has been building on US-Iraqi relations for at least a year. The Trump Administration’s announcement on May 8, 2018 that it was formally withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), caused deep uneasiness in Iraq. Many worried that the increase in US-Iran tensions the move portended would spill over into Iraq’s domestic politics, further polarizing the different parties and factions and jeopardizing efforts to move politics away from the sectarian battles that have been a hallmark of the country’s political scene for 15 years.

The US president’s December 2018 visit to Baghdad enraged Iraqi lawmakers; Trump did not meet with any host-country officials as efforts to arrange a meeting with Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi fell apart over a disagreement about venue.

As if adding insult to injury, the US president’s December 2018 visit to Baghdad enraged Iraqi lawmakers; Trump failed to meet with any host-country officials as efforts to arrange a meeting with Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi fell apart over a disagreement about venue. A number of key political figures, including prominent firebrand cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, responded by accusing Washington of violating Iraq’s sovereignty and demanding that US troops be withdrawn from the country. Qais al-Khazali, head of the Asa‘ib Ahl al-Haq, was even more pointed, tweeting that “Iraqis will respond with a parliamentary decision to oust your [American] military forces. And if they do not leave, we have the experience and the ability to remove them by other means that your forces are familiar with.”

President Trump did not do much subsequently to assuage the ill will. In an interview on the CBS news program “Face the Nation” in February, Trump announced that the US troops sent to Iraq to assist in the fight against the Islamic State in 2014 would remain to keep an eye on Iran, much to the chagrin of Baghdad, which had not been told of any such plan. The statement prompted Iraqi President Barham Salih to warn Trump not to “overburden Iraq with your own issues. The U.S. is a major power … but do not pursue your own policy priorities, we live here.”

Pressure Mounts on Baghdad from Washington and Tehran

The recent tightening of sanctions has contributed to the problem, provoking anger and worry in almost equal measure. After Washington announced its intention in August 2018 to reimpose sanctions on Iran, which had been lifted pursuant to the JCPOA, then-Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi reluctantly indicated Iraq would comply. But he was quickly forced to backtrack after facing a furious reaction from legislators. Despite exemptions and deadline extensions to delay or blunt the full impact of sanctions on Iraq and certain other countries, the problem remains a major concern that has only intensified after subsequent US announcements of new sanctions, with more potentially on the way. Resentment of the United States, never at a low ebb, continues to run high within the Iraqi political class.

Just as the United States has pressured Iraq to limit or cut economic ties with Iran, so Iran has tried to expand its economic interests in Iraq, mainly to counter US policy.

Just as the United States has pressured Iraq to limit or cut economic ties with Iran, so Iran has tried to expand its economic interests in Iraq, mainly to counter US policy. While visiting Baghdad in March, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani expressed confidence that “we can easily increase” economic cooperation from the current $12 billion annually to $20 billion. He added that “when the United States is seeking to pressurize the Iranian nation with its unjust sanctions, we need to develop and deepen our relations [with Iraq] to stand against them.” During the visit the two sides signed a number of agreements covering trade, oil, health, and construction of a Basra-Shalamcheh railroad link in the south. In addition, the National Iranian Oil Company announced May 4 that it would open an office in Baghdad, which is likely to have a broader role in advancing and coordinating the operations of Iranian companies in Iraq.

Baghdad Walks a Tightrope

As this new version of the Great Game takes shape, Iraqi politicians are well aware of their country’s vulnerability to pressure from both sides and the limited options they possess to counteract it.

If fully implemented, US sanctions on Iran could halt Iraqi dealings with US banks, impact business, and negatively affect delivery of basic services. (Washington has pressured Iraq to reduce its energy dependence on Iran, which supplies 40 percent of Iraq’s electricity.) The April 8 US designation of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a major economic powerhouse in construction and other fields, as a “foreign terrorist organization” mandates potential legal consequences for doing business with the IRGC or its affiliated companies and thus has the potential to disrupt hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of joint Iran-Iraq economic projects such as that Basra-Shalamcheh railroad. Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi reacted with dismay, explaining that his government had tried to talk Washington out of the designation, to no avail.

With Iran the situation is even more complicated. Tehran is Baghdad’s top trading partner and energy supplier; any disruption to these ties could spell serious economic trouble for Iraq, not to mention political turmoil as the consequences, particularly potential power outages, hit home. Iran is in a position to divert a significant amount of Iraq’s ground water, if it chooses, through existing dam projects on tributaries of the Tigris River. In addition, Iran has taken over a considerable portion of the Iraqi domestic economy by flooding the market with cheap manufactured goods and foodstuffs, which Iraq would be hard-pressed to replace in the event of a cutoff by Tehran or a sanctions-enforced boycott of Iranian products.

Iran has taken over a considerable portion of the Iraqi domestic economy by flooding the market with cheap manufactured goods and foodstuffs, which Iraq would be hard-pressed to replace in the event of a cutoff by Tehran or a sanctions-enforced boycott of Iranian products.

No wonder, then, that Iraqis fear that US attempts to force their country to disentangle economic ties with Tehran could result in severe damage to their economy without much in the way of US efforts to offset the damage. The risk of angry blowback from Tehran is very real, too. In this atmosphere, armed confrontation between Iran and the United States, or even a prolonged diplomatic standoff at daggers drawn, risks serious complications for the Iraqi government.

Iraqi Steps toward Stronger Arab Ties

Iraq has assiduously cultivated closer political and economic ties with the Arab Gulf states and tried to limit Iran’s commercial sway in order to provide economic alternatives, particularly in the energy field, and insulate Baghdad from American political pressure.

A centerpiece of this effort is Baghdad’s effort to advance relations with Saudi Arabia. Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi visited Riyadh in April at the head of a large business and government delegation, during which the two sides signed 13 agreements on trade, energy, and political issues. For its part, Saudi Arabia, having given the cold shoulder to a succession of Iraqi governments over the years, is now building closer diplomatic ties. On April 4, Riyadh reopened its consulate in Baghdad after a hiatus of 30 years, and it is discussing the inauguration of three others in various Iraqi cities including Najaf, the seat of Iraq’s Shia clerical establishment.

Seeking a Middle Way

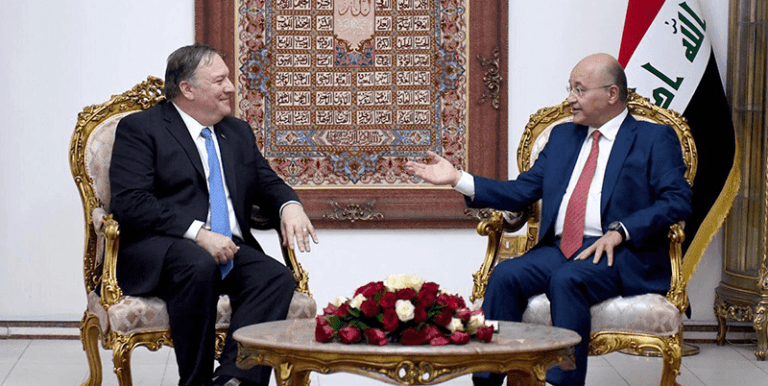

For now, Baghdad has decided to keep its head down and its options open. During a hastily arranged visit by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on May 8, the secretary told Iraqi leaders that if they could not actively aid the United States in the confrontation with Iran they should simply stand aside. The Iraqi government appears determined to take him up on it. Abdul-Mahdi has continued to insist that Iraq will not take sides in regional conflicts; following an April visit to Tehran, his office issued a statement affirming that “Iraq rejects being a part of regional and international axes. Iraq wants to keep its good relationship with all without being a part of an axis against the other.” Even Muqtada Sadr has warned that a US-Iran war would be “the end of Iraq,” and that anyone trying to drag Iraq into one would be “an enemy of the Iraqi people.”

Indeed, Iraq now seems to pin its hopes on the role of potential peacemaker. The prime minister is said to be keen to serve as a mediator between the two sides and to have asked the office of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s chief religious authority, for his assent. During a visit to Tehran May 26, Iraqi Foreign Minister Mohammed al-Hakim publicly affirmed Baghdad’s desire to act as go-between. Neither the United States nor Iran has evinced the least interest in such a role for Iraq, at least up to this point, but it underscores Iraq’s desperation to change the dangerous current dynamic and get out of the line of fire (both figuratively and literally).

Washington Needs to Tread Carefully

The United States needs to think carefully about its relationship with Iraq going forward. Iraq’s stability is vital to the security of close US allies, including Saudi Arabia, and its full reintegration into the Arab world is critically important to US hopes to contain Iran’s influence. The US security relationship with Iraq was crucial in the successful battle to destroy the Islamic State’s “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria and in the continued presence of American troops on Iraqi soil—while often an irritant to various Iraqi factions and militias—and it is an unmistakable show of Washington’s commitment to Iraqi unity and independence. Recklessly pursuing policies that have the effect of further fracturing Iraq’s politics, stoking rage at the United States, provoking demands for the withdrawal of US troops, and driving Iraqi leaders closer to Tehran will seriously undermine US regional goals.

Washington can change course by carving out extensive practical exemptions for Iraq from its sanctions regime, or exempt it altogether, as the United Nations—with US support— excused Jordan from complying with Iraq sanctions in the 1990-2003 period. At the very least, more open-ended deadlines for Iraqi compliance with American sanctions on Iran should be granted, while the United States mounts a concerted effort with the Gulf states and international investors to help Iraq diversify its economy.

More open-ended deadlines for Iraqi compliance with American sanctions on Iran should be granted, while the United States mounts a concerted effort with the Gulf states and international investors to help Iraq diversify its economy.

The administration should also pay much closer attention to the need for defter diplomacy with Iraq, particularly with regard to its public messaging. Washington must take care to communicate respect for Iraqi sovereignty and to express understanding for Baghdad’s complicated relationship with its Iranian neighbor. Consistent and engaged high-level American diplomacy with Baghdad would be helpful as well, much more so than the off-the-cuff presidential pronouncements and occasional emergency visits by the secretary of state that have characterized recent US-Iraq diplomacy.

The Pentagon’s May 24 announcement that it would expand the current US deployment to the Gulf, including 1,500 additional troops, a Patriot anti-missile battery, and a fighter squadron, once again ups the ante and adds new urgency to the situation. It should also add urgency to US thinking on how to protect its relationship with Iraq from the possible severe blowback that could come from a worsening crisis with Iran.