After 257 days of political impasse, Lebanon’s 75th government since independence was formed on January 31. The reaction in Washington and in the American media has been that Hezbollah now controls a majority in the Lebanese government and thus the country. However, putting this development in context is crucial to understanding how and why the cabinet was formed and, most importantly, what challenges it will face moving forward.

The new cabinet reflects the May 2018 parliamentary elections, which led to new dynamics in Lebanese politics. In his third term as prime minister, Saad Hariri oversees a revised version of the past cabinet he led under the presidency of Michel Aoun, hence renewing the presidential deal that brought the two to power in 2016.

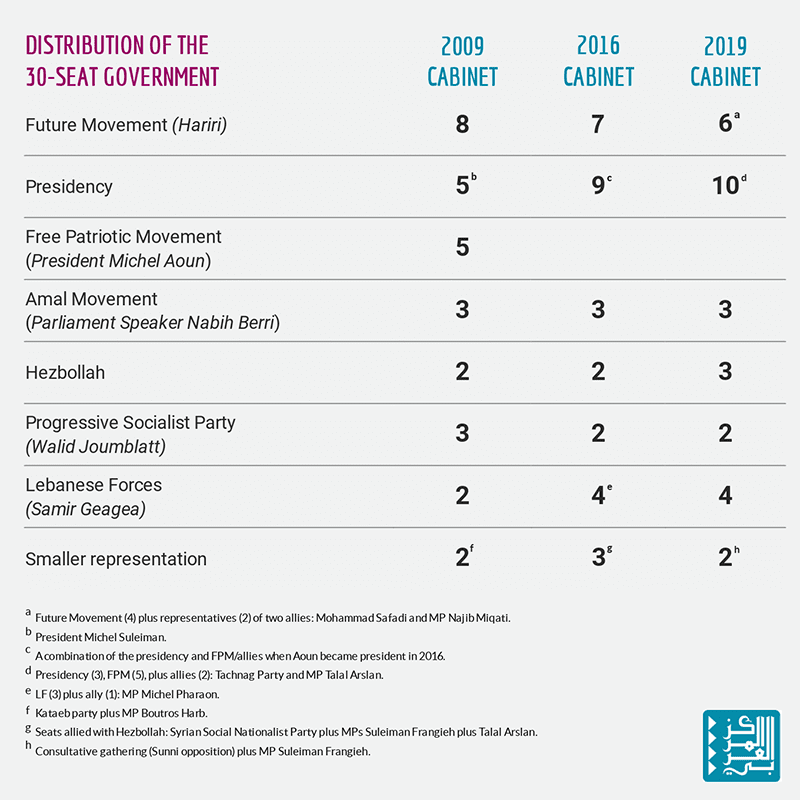

As noted in the chart below, the first 30-seat cabinet led by Hariri in 2009 had a 15-10-5 distribution with 15 seats for the anti-Syrian regime, the March 14 coalition; 10 seats for the March 8 pro-Syrian regime coalition; and five seats for then President Michel Suleiman. While the Hariri-led March 14 Alliance had the majority in 2009, the March 8 Alliance retained the blocking one-third power that forced the government’s resignation in 2011.1 The proportional electoral law of 2016 effectively ended the March 8 and March 14 divide that prevailed in Lebanese governments from 2005 to 2015. Moreover, Hariri’s influence has dwindled over the years with the decline of his wealth and the end of the Saudi financial support he used to receive. This has led to the gradual decrease in Hariri’s cabinet quota from the first government he led in 2009 to the one he announced last week.

As the chart indicates, the 2019 cabinet brought minor changes to the 2016 version, most notably with Hezbollah gaining one extra seat at the expense of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party. The prime minister had to accommodate in his quota two allies from the northern city of Tripoli, former member of parliament Mohammad Safadi and former prime minister and current MP Najib Miqati; he did so by appointing Safadi’s wife, Violette, and Miqati’s protégé, Adel Afiouni, to the cabinet. These appointments will allow him to rally the Sunni community behind him. The landmark of this cabinet is the end of the unilateral confessional representation where one leader takes all the quota representation allocated to his or her own sect.

Resurgence of the Aoun-Hariri Alliance

The most significant domestic factor that facilitated the final push to form the cabinet was the resurgent alliance of Hariri with President Aoun and his son-in-law and foreign minister, Gebran Bassil. This alliance cannot be disregarded in assessing the current state of Lebanese politics. The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) can no longer be considered an exclusive ally of Hezbollah given the growing difference between the two political parties over the past two years on major national security decisions, including how to deal with border and maritime disputes with Israel—though not to the extent of FPM challenging Hezbollah’s armed status.

The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) can no longer be considered an exclusive ally of Hezbollah given the growing difference between the two political parties over the past two years on major national security decisions.

The Aoun-Hariri alliance suffered a setback after the May 2018 parliamentary elections for two major reasons. First, Hariri felt that his poor electoral performance was caused by his base’s rejection of the alliance with Aoun, who had aligned himself with Hezbollah. Second, Hariri’s sacking of his chief of staff and cousin, Nader Hariri––who was the go-between with FPM––deprived the prime minister of a good channel of communication with the president. However, Hariri and Aoun seem to have rekindled their relations in the past few months as the dire economic situation in Lebanon added pressure on Hariri to become more decisive in forming the government. During the past eight months, Hariri has often retreated from playing a leading role in the cabinet formation process, which allowed Bassil to play the role of an intermediary between the prime minister and Hezbollah. The synergy between Hariri and Bassil was apparent even in the selection of their ministers; they ousted the hawks and veterans and replaced them with younger loyal activists, thereby striving to consolidate control over their respective parties.

If there is one case of collateral damage from this new cabinet, it must be Druze leader Walid Joumblatt, who feels besieged on two fronts: the Aoun-Hariri alliance at the national level and the Talal Arslan-Wiam Wahhab alliance on the Druze front. The tensions between Hariri and Joumblatt escalated after the government was announced, hence the latter is emerging as the major opposition force inside the government and might be joined later by Samir Geagea, leader of the Lebanese Forces Party, and others who feel marginalized by the Aoun-Hariri alliance. FPM took the Ministry for the Internally Displaced for the second time from Joumblatt, which was traditionally a major portfolio to preserve his influence in Mount Lebanon. The Ministry of State for Refugee Affairs was also given to his rival Arslan, a portfolio that might strengthen the ties of the Druze community in Lebanon with the Syrian regime because of the existence of about a million displaced Syrians in the country. Arslan already noted2 that returning Syrian refugees to their homes requires engaging Damascus, which, thus far, is an arguable proposition to many Lebanese leaders. Moreover, as the cabinet was announced, Hariri authorized3 the general director of the internal security forces, Major General Imad Othman, to investigate the corruption of officers affiliated with Joumblatt, a move the prime minister refrained from taking previously.

The One-third Blocking Power

In every cabinet in Lebanon since 2005, the most significant issue that stalled the formation process was who had the one-third vote to block major decisions taken by the government. In the 2019 cabinet, Hezbollah has denied FPM from having the one-third blocking vote in the cabinet by ensuring that the Sunni opposition to Hariri is represented within the President-FPM quota. A Sunni opposition leader allied with Hezbollah criticized4 Bassil for trying to run the cabinet and affirmed that their representative in the government is not part of the FPM alliance. The Shia coalition, comprised of Hezbollah and the Amal movement (led by Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri), is expected to play a larger role in this cabinet to counter Hariri and Bassil.

Since the country’s alliances became even more murky after the 2018 parliamentary elections, the one-third criterion calculations might change depending on the issue at hand on the agenda. However, no matter which combination of alliances and scenarios is predicted, it might be difficult to secure a sustainable two-third majority. If Aoun allies himself with the Shia coalition, the March 8 Alliance will not be enough to pass key resolutions. The same applies if Aoun partners with Hariri while Hezbollah and its core allies only have eight ministers. The lineup of the new government means that the cabinet needs to work in minimal harmony to function; otherwise, there will be paralysis.

Since the country’s alliances became even more murky after the 2018 parliamentary elections, the one-third criterion calculations might change depending on the issue at hand on the agenda.

The Government’s Future Challenges

There are two complicated yet interrelated challenges that seem to dominate the agenda of the next Lebanese government: the economy and corruption, and the Syrian refugees and engagement with Damascus.

The dire economic situation is the overarching challenge facing the new Lebanese government and data show it has an uphill road ahead. The country’s public debt is 150 percent of GDP and debt service takes nearly half of government revenues and one third of its total spending. On January 10, Lebanese Finance Minister Ali Hassan Khalil spoke about plans to restructure the public debt, which led to a panic in the Lebanese stock exchange.

The Paris donor conference held in April 2018 pledged $11 billion in loans and grants for Lebanon in exchange for reforms, which include enacting anti-corruption laws, modernizing the public sector (most notably electricity) that is draining the budget, and diversifying the country’s productive sectors. France has been pressuring Lebanese leaders to form a government and begin implementing the reforms package.

Since the May 2018 election campaign, Hezbollah has repeatedly signaled its intention to expand its role in governance by addressing the corruption predicament in the Lebanese system, which has been partially motivated by pressure from the base. Similarly, Aoun appointed a former judge close to him, Albert Serhan, as justice minister, as he hopes to reform the dysfunctional judiciary that suffers from political intervention. Hariri also announced5 that a national commission to combat corruption would be formed and a law would be enacted to protect whistle blowers. However, due to the nature of the political system and the expected tensions within the government, the reform agenda might become hostage to the struggle for influence among Lebanese leaders.

Due to the nature of the political system and the expected tensions within the government, the reform agenda might become hostage to the struggle for influence among Lebanese leaders.

There are increasing signals that the new Lebanese government will deal with the return of Syrian refugees as priority; however, this process remains a difficult one. As the Lebanese foreign minister hinted6 on February 4, an engagement between Beirut and Damascus might be expected at the ministerial level to address the next steps for nearly one million Syrian refugees in Lebanon. With the United States pressuring its Arab allies not to embrace the Syrian regime, the new cabinet is expected to tacitly endorse the engagement with Damascus but restrain it to the ministerial level instead of the presidency or the premiership.

The US-Iran Dynamic and Hezbollah’s Influence

The US objection to giving Hezbollah the health ministry epitomizes the rivalry between Washington and Tehran in Lebanon. However, the US administration had to recognize once again the realities of Lebanese politics; indeed, this issue will cast a cloud over the new Lebanese government without leading to a significant change in US policy toward Lebanon. While welcoming the cabinet formation on February 1, the US State Department called on the new government “to ensure the resources and services of these ministries do not provide support” to Hezbollah. Hariri affirmed7 that relinquishing the health ministry to Hezbollah is “not an embarrassment,” while the party’s Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah noted on February 4 that the Shia group will not use the health ministry “funds for its own benefit.” Nasrallah also asserted8 that Hezbollah’s role in the government “will be influential and essential more than ever before” while continuing his subdued tone in addressing key domestic and regional issues.

While the United States will apply pressure to make sure Hezbollah does not misuse the health ministry’s funds, continuing US engagement with the Lebanese government contributes to the stability of Lebanon.

The new cabinet does not represent a shift in Lebanese politics but reinforces the same trend of the past two years. One should not expect a fragile Lebanese government to rein in Hezbollah, hence the cabinet should not be the barometer to assess Hezbollah’s control of the country. While the United States will apply pressure to make sure Hezbollah does not misuse the health ministry’s funds, continuing US engagement with the Lebanese government contributes to the stability of Lebanon. After nearly nine months of delay, Lebanese leaders agreed on the same parameters as those of the last cabinet, hence there should be no cause for surprise or alarm. What remains key is to ensure that Lebanese leaders take the economic and corruption challenges seriously instead of being entangled in regional conflicts. A US overreaction to the cabinet formation is likely to strengthen Hezbollah’s hold on Lebanese politics. The only effective way to restrain Hezbollah remains within the intricate parameters of the Lebanese political system.

1 According to the Lebanese constitution, major cabinet decisions require a two-third majority, meaning that a third plus one of the ministers can vote down such decisions or force the government to resign if they decide to quit.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.

4 Source is in Arabic.

5 Source is in Arabic.

6 Source is in Arabic.

7 Source is in Arabic.

8 Source is in Arabic.