Despite increasing pressures from Iraqi authorities, the president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), Masoud Barzani, declared that there is no turning back from holding the Kurdish independence referendum which is scheduled to take place on September 25, 2017. KRG officials, however, emphasize that the referendum results would not be binding, and therefore, they would avoid a unilateral declaration of independence without reaching an agreement with Baghdad. Given the longstanding territorial disputes between Erbil and Baghdad, such a mutual understanding may take a few more years, as attested by the head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party’s (KDP) foreign relations. So why push now for an electoral mandate on independence? KRG officials hope that such a mandate would make Erbil better equipped in negotiations with Baghdad. Equally important, the KRG is now testing the waters to see how regional powers as well as the United States respond to its independence bid.

In case the referendum does not bring the expected Kurdish unity, however, the KRG’s bid will be a pyrrhic victory at best. If voter participation proves to be low and the approval rate gets below 80 percent, the referendum may even be an embarrassment for the government. Growing dissent among the opposition indicates that such a scenario is not unlikely. Without a strong electoral mandate—no weaker than the informal1 2005 referendum in which 98 percent of Kurds indicated their willingness to gain independence from Baghdad—Masoud Barzani’s legitimacy will still be questioned, and thus, the hope to gain an upper hand in the negotiations with Baghdad is far-fetched.

Kurdistan’s Parliamentary Crisis and the Referendum

Understanding the need to address mass grievances within Iraqi Kurdistan, President Barzani declared the referendum with a promise to hold parliamentary as well as presidential elections in November 2017. The opposition, however, is skeptical about whether the government will remain committed to holding these elections as scheduled. First, Kurdistan’s High Electoral Committee has not yet set an exact date for the elections due to skirmishes among the committee members—those who are pro-government vs. the opposition. Second, and more importantly, in the case that the referendum results are not satisfactory to the ruling KDP, Barzani is likely to postpone these elections to summer 2018—after the Iraqi elections in April 2018.

In August 2013, at the end of Masoud Barzani’s eight-year presidential term, the Kurdish parliament extended his presidency for another two years. A crisis erupted when Barzani refused to step down in August 2015 and, in a controversial ruling, the Kurdistan Judicial Council extended his term two more years. The main opposition party, the Movement for Change (also known as Gorran), declared such a move unlawful. Soon after, the speaker of the parliament was prevented from entering Erbil and Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani removed four Gorran ministers from his cabinet. Since then, the parliament remains in recess.

Given the fact that the crisis occurred at the height of the war between the KRG and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), President Barzani has emphasized the extraordinary and existential circumstances that the Kurdish nation faces. Behind the parliamentary crisis were serious economic troubles; the government could not pay salaries to civil servants who, in turn, joined strikes and mass street protests in the Sulaymaniyah region. The opposition accused Barzani’s KDP of corruption and financial mismanagement while the government pointed to the impact of the war against ISIL, declining oil prices, Baghdad’s budget cuts as a result of shrinking oil revenues, and the absorption of unprecedented numbers of internally displaced people, which increased Kurdistan’s population by 28 percent. In March 2016, Barzani stated that he would remain in office until he fulfilled his dream—i.e., independent statehood for Kurdistan. As a result, the push for Kurdish independence is now fully entangled with the domestic legitimacy of Barzani’s KDP.

Moreover, an alliance agreement between Gorran and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in May 2016 has alarmed the KDP leadership. The role of the PUK in Iraqi Kurdistan is noteworthy. Originally formed by Jalal Talabani in Sulaymaniyah, the PUK has been, on the one hand, the main historic rival of the KDP. On the other hand, the PUK’s power-sharing with the KDP as part of the KRG government caused a vacuum in Kurdistan’s opposition sphere and split the party. Disenchanted members of the PUK—led by former PUK deputy secretary general Nawshirwan Mustafa—established a new party, Gorran, in 2009.

Gorran grew rapidly within a few years, attracting more parliamentary seats than the PUK in the 2013 popular elections. Since then, the PUK has faced a dilemma. As part of the ruling government, the party has supported the KDP’s handling of the looming crisis. Yet, in order to retain its popular base in Sulaymaniyah, the party leadership expressed some critical views and maintained relatively good ties with Gorran. The PUK supports the referendum bid; however, similar to Gorran and other opposition parties, the PUK is in favor of a parliamentary system for Kurdistan’s future—and thus, it is critical of the presidential system that is envisioned by the KDP.

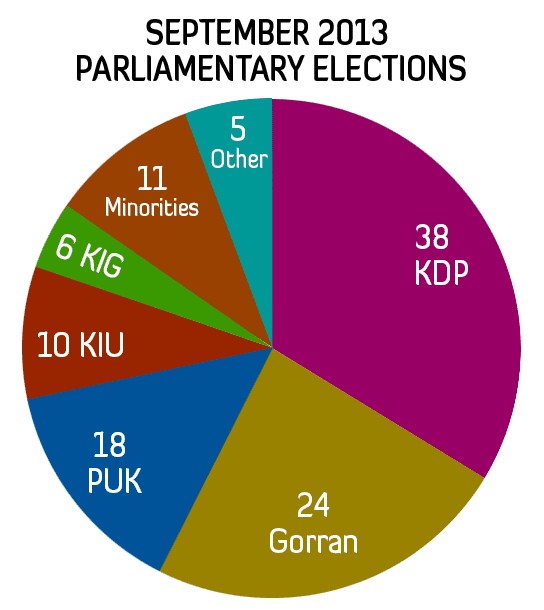

Figure 1. Distribution of seats in Iraqi Kurdistan’s parliament after the popular elections on September 21, 2013.

In the past year, the KDP leadership has been successful in upsetting the PUK-Gorran agreement by offering incentives to PUK leaders. The current distribution of Parliamentary seats would give an upper hand to the opposition if the two parties acted jointly (see Figure 1). A year after Jalal Talabani and Nawshirwan Mustafa signed the 25-article joint action plan, both parties now blame each other for not honoring the agreement. Although the PUK-Gorran alliance is hard to fulfill as the two are competing to win over the same Kurdish constituency in the Sulaymaniyah and Halabja provinces, this alliance is still significant in shaping internal Kurdish politics. The PUK, for example, recently boycotted Barzani’s referendum preparation meeting and released a joint declaration with Gorran to call on the government to reactivate Kurdistan’s parliament before the referendum.

The upcoming parliamentary elections will also foretell Gorran’s future in the wake of the May 2017 death of the party’s legendary leader Nawshirwan Mustafa. The party still faces a deep crisis in finding a unifying leader. Historically, Kurdish society has deeply revered charismatic leaders and pledged allegiance to such figures rather than to political parties. There is a growing hope among PUK deputies that Gorran may face internal divisions as well as decreasing voter support in the upcoming parliamentary elections, and consequently, some Gorran members might rejoin the PUK. Under such a scenario, the PUK may expect to reap benefits as it becomes the main opposition in parliament once again. The PUK, however, has also suffered from internal divisions in recent years due to the deteriorating health of its founding leader Jalal Talabani. Thus, there seems to be a leadership vacuum in Kurdistan’s oppositional sphere once again. The vacuum is now not only exploited by the ruling KDP but also by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), whose growing activism in the Sinjar region has raised eyebrows in Erbil and led to armed clashes between security forces and local militia units.

Holding a Referendum in the Disputed Territories: A Wise Strategy?

In his op-ed piece in the Washington Post, President Barzani wrote that the most contentious issue for Kurdish independence will be the disputed territories. Barzani noted Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution, which allows the people of disputed areas to decide their own future with popular referendums, adding that the KRG will propose this during the September referendum despite Baghdad’s objections.

As the war against ISIL in Iraq nears an end, some analysts see value in Barzani’s strategy to fortify Kurdish gains in oil-rich Kirkuk’s surroundings. ISIL’s retreat from the disputed territories led to increasing control by the central government, which now threatens to weaken the Kurds’ negotiating power with Baghdad. The independence referendum, therefore, is a strategic move to reap the political advantage of the military success on the ground. As the referendum is non-binding and does not necessarily mean a total break from Baghdad, it may well serve Kurdish goals to gain concessions from the central government. According to the Kurdish electoral commission, around 3,650,000 voters who are living in “Kurdistani areas outside the administration of the Kurdistan region” are eligible to participate in the referendum.

Such a contentious escalation, however, may be counterproductive for Erbil. In a heated atmosphere, Baghdad appears to have the upper hand and an escalation dominance. The city infrastructure and basic needs in disputed territories still largely depend on the central government. More importantly, as Iraqi elections in April 2018 are fast approaching, hawkish elements in the Baghdad regime will exploit ethnic and sectarian fears by targeting Kurds. Thus, an aggressive push in the disputed territories may trigger a reaction that may harm Kurdish aspirations in the long run. “The last thing we want,” admits Barzani, is “a long-lasting territorial dispute with Iraq that could poison our future relations.”

In fact, compared to the status of Kurds in Iraq now, full independence may usher a better future for Kurdistan only and solely if Erbil and Baghdad have working relations. Kurdistan’s current autonomy is already comparable to an independent state: the KRG has its own security apparatus and military forces, draws from direct foreign investments, and pursues an independent foreign policy.

Mixed Signals from Washington

What follows the non-binding referendum in September will also be dependent on US strategy in the region after the Mosul operation against ISIL. Policy circles in Washington appear to be divided on Kurdistan’s independence in the short term. Referring to a CIA assessment document, former CIA director David Petraeus argued that Kurdistan cannot possibly afford to be independent due to financial difficulties. President Barzani, however, trusts his good ties with certain high ranking officials in the Trump Administration who are less committed to Iraq’s unity. Thus far, the official statements herald a rocky road for Barzani. Brett McGurk, the US Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIS, recently delivered Washington’s rejection of the referendum, as the war on ISIL will continue in western Iraq after the Mosul campaign ends.

Washington’s real challenge, perhaps, is the complex puzzle that faces post-ISIL Iraq. What will be the future of Sunni Arabs in the absence of Kurds? Turkey’s repeated calls for the unity of Iraq against Kurdish independence, for example, is not simply a reaction to Kurdish nationalism but also an expression of growing concern about sectarian fracturing in the country, where Kurds have been playing a positive and cohesive role. Despite Turkish objections, however, it is likely that Ankara will keep its close ties to the Barzani regime. Ankara’s economic as well as strategic partnership with Erbil has become so strong that a fallout may harm both parties.

For Washington, the elephant in the room is not Turkey but Iran. Without a long-lasting agreement between Erbil and Baghdad, an independent Kurdistan may increase Tehran’s fear that American and Turkish influence will prevail in a critical region that is adjacent to Iran’s Kurdistan. What increases such fears is the fact that the major Kurdish political parties have now returned to arms against the Islamic Republic and have begun launching attacks. Tehran’s hardliners find their echo in former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s statement that “the use of force may be necessary” to deter the KRG’s policy to establish “a greater Kurdistan.”

Hence, Washington’s decision regarding Kurdistan’s independence is no longer separable from the changing course of Iranian policy under the Trump Administration. Regarding American interests in the Gulf region, an independent Kurdistan may have little more to offer than the current status quo, while this involves too many risks. That Baghdad will be further pushed into Iran’s orbit is a serious matter in itself that will result in serious complications.

Regarding Kurdistan’s current parliamentary crisis, Washington may play a positive role in brokering a deal among parties. A priority for US strategic interests is the long-term stability of Iraqi Kurdistan, which is now plagued with deep mistrust, increasing frustration among the youth, and serious financial struggles. A working parliament and functioning democracy may better serve Kurdish unity than a referendum that aims to dismiss the opposition’s demands.

1 Young Kurdish officials conducted an informal referendum on Kurdish independence outside of voting booths in January 2005 in Kurdish areas of Iraq.