In all initiatives and negotiations for a final and peaceful settlement between Israel and Palestine, Jerusalem has proved to be the toughest final-status issue among those that were left to be resolved in negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians following the Oslo Accords. Al-Aqsa Mosque/al-Haram al-Sharif (The Noble Sanctuary) has emerged as the paramount obstacle in the standoff, one that continues to grow as a result of Israel’s repeated and ongoing violations of the Status Quo in Jerusalem.

Located in Jerusalem’s Old City, al-Haram al-Sharif is Islam’s third holiest site after Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia. It is 144,000 m² in area, and includes the Qibli Mosque of Al-Aqsa, the Dome of the Rock, and all of the buildings, courtyards, and environs above and beneath the ground. It also includes all waqf (Islamic endowment) properties connected to Al-Aqsa Mosque.

Muslims believe that the prophet Muhammad was transported on a winged steed from the Great Mosque of Mecca to the place where Al-Aqsa Mosque stands today, and from there ascended to heaven. This night journey, also known as Isra’ and Mi’raj, is one of the most important events in the Islamic calendar.

The Dome of the Rock, which is part of the Al-Aqsa compound, was first completed in 691 CE and is one of the oldest extant Islamic structures. It contains the Noble Rock, which is also known as the Pierced Stone because it has a small hole that leads to an underground chamber known as the Well of Souls, where according to the Islamic faith the dead can be heard waiting for Judgment Day.

In Judaism, the compound is referred to as the Temple Mount, and is often considered by Orthodox Jews to be the holiest site in the religion. According to Jewish tradition, the first and second temples were built there, and it is believed that the third temple will be rebuilt on the site at the coming of the Messiah. Traditional Jewish law strictly forbids Jews ascending to the site out of fear of treading on sacred ground. However, a number of Zionist religious organizations backed by prominent figures from the Israeli political elite have formed with the primary objective of realizing the immediate construction of the temple and securing Jewish prayer rights on the Mount.

In 2016, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) passed one of its most important resolutions regarding Al-Aqsa Mosque. Document 200 EX/25, known as the Occupied Palestine Resolution, strongly condemned Israel’s escalating aggression and illegal measures against the Al-Aqsa waqf and its personnel—including guards, religious figures, and Muslim worshippers generally—called for the restoration of access for Muslims to their holy site, and demanded that Israel respect the historical Status Quo and immediately cease attacks and abuses that inflame tensions. The resolution sparked outrage among Israeli figures, mainly because of the terminology used in the text, which referred to the site only by its Muslim name, al-Haram al-Sharif, and spoke of it as an exclusively Muslim site.

Since the 19th century, the Al-Aqsa compound has been governed by a Status Quo arrangement, a modus vivendi that prevents discord among conflicting parties.

Since the 19th century, the Al-Aqsa compound has been governed by a Status Quo arrangement, a modus vivendi that prevents discord among conflicting parties. Accordingly, Al-Aqsa’s administration belongs to a Muslim institution, the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf, which is under the custodianship of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. This custodianship has repeatedly been reaffirmed and recognized by the international community, including the United Nations, UNESCO, the Arab League, the European Union, Russia, and the United States, and was officially recognized in the 1994 peace treaty between Israel and Jordan.

The Status Quo as a Legally Binding Framework

After many disputes among European states in the 19th century for control over various holy sites in Jerusalem, the Ottoman Empire issued a series of decrees to regulate the administration of Christian holy sites by determining the powers and rights of various denominations in these places. The most important of these decrees was an 1852 firman by the Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid I, which preserved the possession and division of Christian holy sites in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and forbade any alterations to the status of these sites. This arrangement became known as the Status Quo.

In 1878, Jerusalem’s Status Quo arrangement was internationally recognized in the Treaty of Berlin, which was signed between European powers and the Ottoman Empire following the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

In 1878, the Status Quo was internationally recognized in the Treaty of Berlin, which was signed between European powers and the Ottoman Empire following the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Article 62 of the treaty stated that: “It is well understood that no alteration can be made to the status quo in the holy places.” Article 62 of the Berlin Treaty extended the Status Quo to include all holy places and not only Christian sites. The Status Quo arrangement is a unique and delicate legal system that contains a specific set of rights and obligations that were created over centuries of practice and are now considered binding international law. It therefore supersedes any and all aspects of domestic law.

After the establishment of the British Mandate of Palestine, the first violation of the Status Quo arrangement in Al-Aqsa Mosque occurred in 1929 when a Jewish-Zionist group performed prayers for Yom Kippur in front of al-Buraq Wall (also referred to as the Western Wall), sparking a period of significant turbulence in Jerusalem that quickly developed into deadly protests that resulted in the death of 249 Jews and Palestinians. The group claimed rights over al-Buraq Wall, but no evidence was brought to confirm their claims. In response, British Mandate authorities established an ad hoc commission to determine the rights and claims in connection with al-Buraq Wall. The commission determined that the wall forms an integral part of Al-Aqsa Mosque, and is therefore a Muslim property.

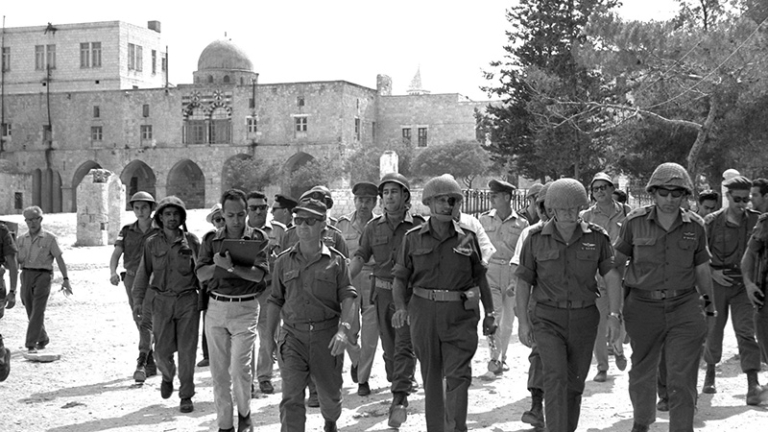

Following its victory in the 1967 war, Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and unilaterally declared sovereignty over East Jerusalem, an area approximately 70.5 km² large, where the Old City and Al-Aqsa Mosque are located. Israel then proceeded to apply its domestic laws to the area, placing it under the administration of the state-run Jerusalem Municipality, a blatant violation of international law. The UN Security Council and other international organizations passed dozens of resolutions regarding the move, unambiguously reiterating the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war,” and required Israel to withdraw its armed forces from territories it had occupied during the 1967 war. However, Israel’s colonial aspirations with respect to East Jerusalem were only further institutionalized. In 1980 Israel enacted “Basic Law: Jerusalem the Capital of Israel,” which declared that “the complete and united Jerusalem is the capital of Israel.” The law aroused resentment in the international community and in the UN Security Council, which vigorously condemned Israel for passing the law on the grounds that it violated international law, and determined in UN Resolution 478 that “all legislative and administrative measures and actions taken by Israel, the Occupying Power, which have altered or purport to alter the character and the status of the Holy City of Jerusalem, and in particular, the recent ‘basic law’ on Jerusalem, are null and void.”

In the course of the 1967 occupation of the eastern part of Jerusalem, Israel recognized the Status Quo arrangement as the legally binding framework regulating the administration of the Al-Aqsa compound. Nevertheless, Israeli authorities seized control over al-Buraq Wall, confiscated the keys of al-Magharbeh Gate, and razed the Moroccan Quarter, which was established in the 12th century and contained 135 houses and three mosques, building in its place what is known today as the Western Plaza. Israel’s recognition of the Status Quo arrangement in the Al-Aqsa compound was due to two factors: international consensus that East Jerusalem is an occupied territory, and fear that breaching the Status Quo in the Muslim shrine would ignite opposition in the Middle East.

Given its status as the prevailing legal framework, parties in the dispute are obliged to refrain from instituting any change to the Status Quo or any of its components. These components include access regulations (including visiting hours, number of visits, areas open for visitation, and rules of conduct therein); control over the area (including excavations and maintenance); religious rituals and prayers (including their number and time); and rules regarding dress, the character of the site, and police and security protocols. Changes to any of these components by one party are a breach of the Status Quo arrangement, and such a breach carries great potential to cause widespread violence and instability.

Until August 2000, and despite occasional breaches and escalations, the Status Quo functioned relatively smoothly, with the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf collecting small fees from non-Muslims and tourists, who were allowed to enter the holy site provided they followed the rules of the Waqf. Meanwhile, Israel abided by Jordan’s ban on non-Muslim prayers at the holy site, and the Israeli antiquities authority performed low-profile supervision on archeology and maintenance at the compound. However, things changed in September 2000, when Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon entered Al-Aqsa compound escorted by 1,000 Israeli police personnel and sparked the second Palestinian intifada, in which the death toll surpassed 3,000 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis.

During the second intifada, which lasted from 2001 to 2003, non-Muslims were banned from entering Al-Aqsa. In August 2003, a few months after Sharon was elected prime minister, Israel unilaterally and without Jordan’s agreement restored access to the site to Jews and other non-Muslims, despite the coordination of access being a central component of the Status Quo.

Since then, there have been three main components of the Status Quo arrangement in the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound that Israel, through its different executive branches, regularly violates, thereby disregarding the legally binding nature of the arrangement and the explosive potential such violations could ignite in the region:

Access and Freedom of Movement: Today, Israeli occupation forces are stationed inside the holy site, and they completely control the entrance of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Although Muslims are allowed to enter from all gates, non-Muslims can only enter through al-Magharbeh Gate. Temple Mount groups and Israeli extremists enter from al-Magharbeh Gate as well, and the Waqf is prohibited from preventing them from entering the site. The Waqf can no longer prevent Israelis in military fatigues from entering, although this act is banned per the mosque’s regulations. Israeli occupation authorities have systematically limited Palestinians’ access to the compound, and even went as far as prohibiting Palestinian Muslims from entering their holy site while allowing exclusive access to Jews, in violation of the Status Quo, and of the right to freedom of worship, freedom of access, and freedom of expression.

Israeli occupation authorities have systematically limited Palestinians’ access to the compound, and even went as far as prohibiting Palestinian Muslims from entering their holy site while allowing exclusive access to Jews.

The Right to Worship: Al-Aqsa compound is an exclusively Muslim holy site in which non-Muslims are not permitted to pray or perform religious rituals, but are allowed, under the supervision of the Waqf, to visit during regulated visiting hours. Temple Mount activists, including senior Israeli government officials, frequently make attempts to secure the right to hold Jewish prayers at the site, despite the prohibition on non-Muslim prayers. Officials frame their endeavors using the language of civil rights, while activists explicitly call for changing the Status Quo, claiming the existence of an inherent historical right for Jews to pray in Al-Aqsa, despite the lack of any evidence in living memory. Jewish prayers and entries into the compound (referred to as incursions) are increasing, and are perceived by Muslims and Palestinians as extremely provocative, arousing Palestinian fear of an Israeli partition plan for the holy site.

Excavations and Maintenance: As they form an integral part of the holy site’s administration under the Status Quo arrangement, excavations and maintenance must be carried out by the Waqf. Nevertheless, Israel has conducted many illegal and unauthorized excavations, resulting in at least 20 attempts to dig tunnels under the mosque. UNESCO has again and again called on Israel to halt the digging, stressing the illegality of such actions in an occupied territory. In 2000, the Israeli antiquities authority began supervision at the site, which included daily patrolling and photographing in the compound. The Israeli police further prohibited tractors and trucks from operating in the site under Waqf supervision, thereby limiting projects and maintenance to those that can be accomplished with small, non-mechanical tools.

Over the past few years, Al-Aqsa Mosque has been subjected to numerous attacks by Israeli occupation forces, which completely disregard and disrespect its sanctity. Under the guise of law enforcement, the Israeli occupation police stormed the al-Qibli prayer hall on multiple occasions, lobbing stun grenades and attacking worshippers, desecrating the interior space of the prayer hall by stepping on its carpets with their shoes, and intimidating worshippers who were present there. Israel’s settler-colonial agenda is the driving force behind its breaches of the Status Quo, and this should be understood for what it is: cultural cleansing as a tactic of Israeli settler-colonial aspirations. On May 29, 2022, Israeli occupation authorities allowed 2,600 Israeli settlers to storm into Al-Aqsa, raising Israeli flags and reciting Jewish prayers. The settlers were part of the annual “flag march,” which celebrates Israel’s occupation of the eastern part of the city in 1967, which it refers to as the “unification” of Jerusalem.

The climate of impunity that Israel enjoys, and within which it operates, enables it to continue its unabated breaches of the Status Quo. It further enables Israel to maintain its protracted occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, which many believe amounts to the crime of apartheid. Al-Aqsa Mosque is a religious site but it is also a national symbol and a site at which many Palestinians believe their last stand will be. Breaching the Status Quo has already cost many lives, and if the balance is not restored, the next escalation is only a matter of time.

Featured image credit: GPO