Despite the support that Iraq’s new prime minister, Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani, has received from pro-Iran factions in the Iraqi Parliament, he is likely to pursue the objective of balance in Iraq’s foreign policy. This will include maintaining cordial relations with both Iran and the United States, while also making sure not to burn the bridges to the rest of the Arab world that his recent predecessors worked to develop. Although there will likely be efforts by Iran and its Iraqi allies to compel Sudani to distance Iraq from the United States and from Arab states, he is likely to resist such pressure as much as possible because he sees a balanced foreign policy as necessary to preserve his country’s independence, to aid its troubled economy, and to keep remnants of the so-called Islamic State (IS) from resurging.

Having Pro-Iran Friends Does Not Mean Being in Iran’s Pocket

Sudani comes from a family that has included members of the Shia Islamist Dawa Party who opposed Saddam Hussein’s regime, which in return made Dawa Party membership a capital offense. And Sudani’s father and five other family members were reportedly executed by Hussein’s henchmen. However, unlike many other Dawa members who spent years in exile in Iran, Sudani, who was born in 1970, stayed in Iraq, maintaining a low profile while pursuing agricultural studies until the regime was overthrown in 2003 by the US-led invasion. Sudani entered politics the following year, becoming the mayor of the city of Amara, and later the governor of Maysan Province. He subsequently hitched his wagon to then Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who appointed him to several ministerial posts. But even after Maliki was forced to resign in 2014 in the wake of gains made by IS, Sudani was kept on by his successors as acting minister of trade in 2015 and acting minister of industry and minerals in 2016 because of his managerial competence.

Over the course of his political career, Sudani has developed friendly ties with pro-Iran Iraqi politicians and factions, ties that undoubtedly worked to his advantage.

Over the course of his political career, Sudani has developed friendly ties with pro-Iran Iraqi politicians and factions, ties that undoubtedly worked to his advantage when, on October 27 2022, the Iraqi Parliament finally settled on choosing him as prime minister after a year of political turmoil that included the withdrawal of Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s large political faction from the country’s legislative body. The fact that the pro-Iran Coordination Framework, which includes Maliki’s party as well as other Shia parties and elements of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), endorsed Sudani for prime minister has made it appear that he is in Tehran’s pocket. Sudani further fueled this perception in some circles when he appointed controversial pro-Iran figures to his government, including Minister of Higher Education Naim al-Aboudi, of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, a pro-Iran Shia militia that Washington has designated as a terrorist organization, and head of the prime minister’s press office Rabee Nader, who previously worked for the same organization, as well as for Kata’ib Hezbollah, which has the same designation.

Meanwhile, Iranian authorities are seeing the emergence of the new Iraqi government as a victory. The commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Hossein Salami, included earlier unsuccessful attempts at forming an Iraqi government in a litany of what he claimed were the United States’ many failures in the Middle East. Iran’s ambassador to Iraq hurried to pay Sudani a cordial visit, underscoring that he hoped that the Iranian-Iraqi relationship would be strengthened under his premiership.

However, any Iraqi prime minister is likely to have cordial relations with Iran given the extensive trade and religious ties established between the two states since 2003. Iraq is Iran’s second largest export market, and Baghdad has long relied on Iran for electricity and natural gas imports—a fact that Washington has recognized and for which it has given Iraq numerous exemptions from US sanctions imposing penalties on countries that do business with Iran. Moreover, each year since 2003, tens of thousands of Iranian pilgrims visit Shia holy sites in Najaf and Karbala, which has helped to boost the economy in southern Iraq. Even Sudani’s predecessor, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who was considered close to the United States, kept Iraqi-Iranian relations on an even keel, and even visited Tehran.

Sudani Wants US Relations to Continue

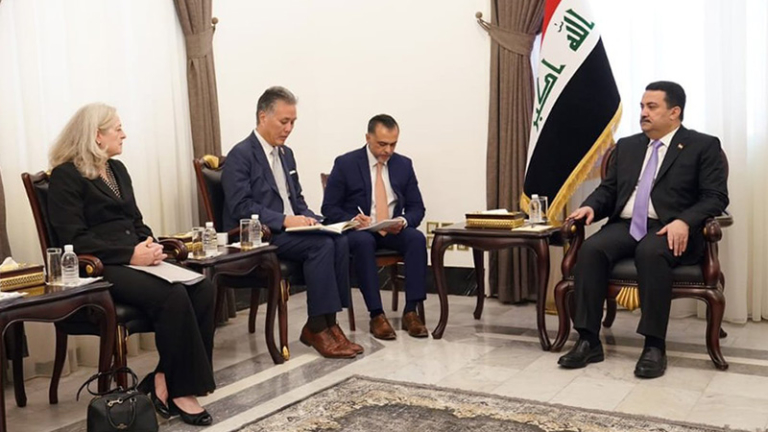

Although US policymakers probably hoped that Kadhimi would stay on as prime minister since he was a known quantity—a former Iraqi intelligence official who generally worked well with US officials—they are now signaling that they want to establish a close relationship with Sudani, who has reciprocated in kind. On October 17, even before he was officially made prime minister, Sudani met with US Ambassador to Iraq Alina Romanowski and reportedly said that he would like to enhance the Strategic Framework Agreement with the United States. In particular, Sudani said that he wanted to strengthen cooperation in the security sphere, with the US continuing to provide support and advice to Iraq’s security forces. This does not sound like a leader wanting to jettison the US role in Iraq at the behest of Tehran.

Although US policymakers probably hoped that Kadhimi would stay on as prime minister since he was a known quantity, they are now signaling that they want to establish a close relationship with Sudani.

There are currently about 2,500 US military personnel in Iraq helping to train the Iraqi military and giving advice on how to deal with the threat posed by remnants of IS. Although IS has been severely weakened in both Iraq and Syria, its cells remain active in both countries and periodically carry out attacks. Sudani appears to realize that the Iraqi military would be disadvantaged in its fight against IS if US trainers were to withdraw from the country because the Iraqi military still needs to improve its capabilities in order to be capable of fighting alone. Moreover, one of Sudani’s promises when he became prime minister was to ensure that areas of Iraq that were damaged during the anti-IS campaign be rebuilt. To be sure, this can only be done if IS is not able to re-emerge in these distressed regions. Furthermore, a perhaps unstated reason for keeping the US military presence in Iraq is to serve as a counterbalance to the IRGC and Iraq’s pro-Iran militias.

On November 3, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken phoned Sudani to congratulate him on his appointment as premier, underscoring that Washington was “eager” to work with his government to improve human rights, fight corruption, increase economic opportunities, and address energy independence and climate issues. Blinken also reaffirmed the United States’ commitment to “supporting Iraq in the enduring defeat” of IS.

These statements clearly indicate that despite the support Sudani has received from the pro-Iran camp, Washington hopes that the cooperation Kadhimi provided will continue under Sudani. However, US support comes with a couple of caveats. US officials reportedly told Sudani in recent weeks that they will not deal with any Iraqi government officials who are affiliated with pro-Iran militias that the US has designated as terrorist groups, such as Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. Washington will also be watching to see if these militias step up their attacks on US forces in Iraq, thereby signaling that Sudani should do what he can to control them. That said, as of mid-November, the Biden administration was reportedly satisfied with the engagement it has had with Sudani, but will judge his independence from Iran by his actions.

The fact that Sudani has retained the intelligence portfolio for himself instead of giving it to a member of the Coordination Framework may be a signal to Washington that he will try to accommodate US wishes to some degree.

This may be a tall order for Sudani given that even Kadhimi could not control these pro-Iran militias as much as he wanted to. Nonetheless, the fact that Sudani has retained the intelligence portfolio for himself instead of giving it to a member of the Coordination Framework may be a signal to Washington that he will try to accommodate US wishes to some degree.

Sudani has also signaled that he will not be part of an OPEC+ move to cut back on oil production in order to keep prices high. Instead, he told reporters that Iraq cannot afford a production cut because it needs as much revenue as possible to deal with the country’s myriad economic problems. These include an estimated youth unemployment rate of more than 27 percent and a poverty rate of 31 percent, recorded in 2021. Sudani undoubtedly sees his resistance to production cuts as being in Iraq’s economic interest, but it also has the ancillary effect of keeping him in the good graces of the Biden administration, which wants as much oil on the world market as possible so as to lower prices. Interestingly, Russian President Vladimir Putin phoned Sudani on November 24 to pledge his friendship with the new prime minister and to complain about western countries’ attempt to impose a price cap on their imports of Russian oil. But it appears that Putin did not make any headway on changing Sudani’s mind regarding cuts in oil production.

Maintaining Arab World Connections

Significantly, Sudani’s first foreign trip as prime minister was not to Iran, but to the neighboring Arab state of Jordan, in a visit that took place on November 21. Sudani and the governor of Iraq’s Anbar Province, which borders Jordan, met with King Abdullah and other Jordanian officials, assuring them that previous agreements (notably the ones signed by the Kadhimi government on pipelines and electric grid connections) would remain in place. This represented an important moment for Iraqi-Jordanian ties going forward because the Iraqi Parliament in early November canceled all the decrees that Kadhimi’s caretaker government had issued since October 8, 2021. Sudani’s trip to Jordan not only reaffirmed these ties, but may have also reasserted the development of an Iraq-Jordan-Egypt nexus that has been in the works for the last couple of years. For example, a proposed oil pipeline stretching from Basra in Iraq to the Jordanian port of Aqaba may extend to Egypt as well, thereby serving all three countries.

Sudani also addressed Iraq’s relations with Saudi Arabia, praising the kingdom for its leading role in the region and highlighting the political and economic ties that the two countries have developed over the past several years.

Sudani also addressed Iraq’s relations with Saudi Arabia, praising the kingdom for its leading role in the region and highlighting the political and economic ties that the two countries have developed over the past several years, as well as the functioning of their joint Supreme Coordination Council. On the issue of an electrical interconnection proposal to join Iraq to Saudi Arabia’s electrical grid, Sudani—surely with Jordan in mind—stated diplomatically, “More than one proposal can be activated in a way that develops the relationship on the economic side, and unifies positions and coordination towards various issues that concern the stability of the region.”

Saudi officials, however, seem hesitant about Sudani at this point, and uneasy about how close he may be to Iran and to Nouri al-Maliki, whom the Saudis viewed with suspicion because of his anti-Sunni policies. While the leaders of the UAE and Qatar phoned Sudani to congratulate him on his premiership, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has yet to do so, having instead sent Sudani a letter that wished him “progress” and “advancement” in his new position.

Perhaps sensing this hesitancy, on November 1, Sudani said that he hopes to continue hosting talks in Baghdad between Saudi and Iranian officials, which have so far taken place periodically. Sudani, like his predecessor Kadhimi, undoubtedly hopes that by lowering the temperature of tensions between Riyadh and Tehran, Iraq could be seen as a useful regional partner, particularly for Saudi Arabia. So far, however, the talks have not yielded much progress. The danger for Iraq is that if such talks fail and if Iran tries to pressure Iraq to reduce its ties with Riyadh, Sudani will be in a tight spot, especially given that his support in parliament rests with the pro-Iran camp.

Recommendations for US Policy

US officials would be wise to continue to give Sudani substantial leeway as he develops his balanced foreign policy. The new prime minister seems intelligent enough to maneuver in regional politics, even though he is beholden to his pro-Iran backers within the Iraqi Parliament. The fact that he has not called on the US to withdraw its troops from Iraq is an important indicator of this balancing act. In the meantime, US officials should encourage Iraq’s Arab neighbors to continue to reach out to Sudani and his new government and to support the economic projects that his predecessor began, which would make Iraq less dependent on Iran. Weening Iraq off of its electricity and gas dependence on Iran would be in the interest of both the countries of the Arab world and the United States.

The United States’ opposition to certain controversial members of Sudani’s government who have ties to Iraq’s pro-Iran militias is likely to be a strain on Iraqi-US relations going forward. Such matters should be handled quietly, however, as highlighting them would likely result in backlash. As long as such figures are not in influential positions that would directly harm US-Iraqi relations, US policymakers should give Sudani the benefit of the doubt, since he undoubtedly has a better sense of the nuances of Iraqi politics than Washington does. Given the power of the country’s Shia political factions and pro-Iran militias, there is only so much the United States can do to influence the course of events in Iraq. Giving Sudani the time and space to handle both domestic reforms and foreign policy matters, while still supporting Iraq politically and economically, is what is needed at this point, despite misgivings stemming from Sudani’s supposedly pro-Iran posture.

Featured image credit: Twitter/@USAmbIraq