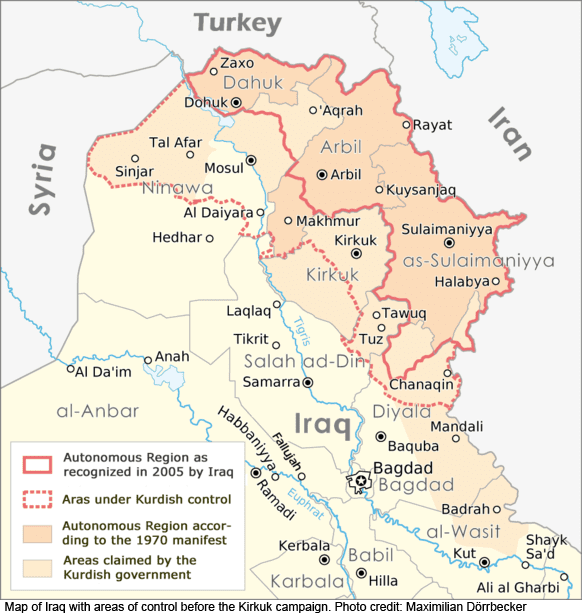

Backed by Shia militias, the Iraqi Army has recently taken control of the territories disputed by the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), pushing Kurds back to the borders of the pre-2003 US-led invasion. As a result, the KRG has lost not only an important swath of strategic locations for its security but also massive amounts of oil revenue. Iraqi forces silently took control of Turkey’s Habur crossing from the KRG for the first time since 1991. Such a humiliating defeat now threatens the unity of the KRG as Kurdish leaders blame each other, with factions emerging within the major parties—the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). As a final blow, Baghdad has decided to cut the budget for the KRG in 2018 from 17 to 12.6 percent, dismissively calling Kurdistan the “provinces of the north” of the country.

Dramatic events in the past few weeks will have long-lasting influence in shaping the future of Iraq’s disputed territories. Despite its acquiescence to Baghdad’s use of force against the Kurds, the US State Department has warned that “the reassertion of federal authority over disputed areas in no way changes their status…they remain disputed until their status is resolved in accordance with the Iraqi constitution.” Ironically, few months ago, KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani claimed that there no longer was such a phrase as “disputed territories” in the KRG dictionary. With a radical shake-up in power dynamics, Baghdad now has the upper hand, and thus, it is reluctant to negotiate over oil revenues and the devolution of federal government powers to local authorities.

Two major factors in shaping the future of Iraq’s disputed territories are new population dynamics, with the influx of internal refugees, and the regional power play between Turkey and Iran. The KRG’s internal divisions will also pose a challenge to Washington’s role in mitigating conflict in the disputed territories.

The Kirkuk Puzzle

Turkey’s agreement with Iran after the Kurdish referendum on September 25 has transformed the strategic calculus of Kurdish leaders in Irbil. Ankara surprisingly did not object to the military operations of Shia militias in disputed territories, insisting on its demand for the KRG to annul the referendum. Irbil appears to underestimate Turkey’s real concerns over Iraq’s territorial integrity. Although Ankara and Irbil have developed remarkable economic ties in the past decade, the perceptions in Turkey regarding security needs are rapidly transforming in favor of the central government in Baghdad. This is especially after Turkey’s involvement in the Syrian war to contain Kurdish enclaves and the failed coup attempt in July 2016, which led to the rise of Turkish nationalism in the state bureaucracy. In addition, Ankara has invested in carving influence in the Nineveh region through Sunni Arab local leaders who viewed the KRG referendum in disputed territories as threatening and illegitimate. Among the primary motives behind Turkey’s harsh reprimand to the KRG was the Kirkuk issue.

Turkey has long perceived Kirkuk as a Turkmen city, and thus, it sought to empower the Turkmen population’s share in Kirkuk’s oil revenues and local governance structures. Backed by Ankara, the Turkmen Front in the Iraqi parliament recently proposed a formula to share local official positions on an equal basis—32 percent for each of Turkmens, Kurds, and Arabs, with the remaining 4 percent for Chaldeans and Assyrians. The 32 percent formula, in fact, was first introduced by the late former Iraqi President Jalal Talabani; however, the Kurdish Peshmerga’s seizure of Kirkuk during the war against the Islamic State (IS) in 2014 has changed Kurdish expectations. KRG leaders repeatedly declared that Kirkuk is part of Kurdistan’s territory and that the Iraqi Army would never return to the city. The current Turkmen proposal, therefore, looks unacceptable to many Kurdish lawmakers—despite the fact that, since October 16, the Iraqi Army has taken full control of the city.

The KRG will likely demand the implementation of Article 140 in the 2005 Iraqi constitution, which envisioned finalizing the settlement of the disputed territories question in three steps: 1) a normalization process in which there is a resettlement of the people displaced during the Arabization campaign under Saddam Hussein; 2) the collection of official census data; and 3) a popular referendum to determine whether the territories will join the autonomous Kurdish region or the central authority. Since then, however, the KRG has launched a systematic campaign for Kurdish resettlement in Kirkuk and Nineveh, changing the demographics considerably. Human rights organizations accused the KRG of “Kurdification” of the disputed territories by expelling Assyrian and Yezidi communities and employing “heavy handed tactics, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, and intimidation, directed at anyone resistant to Kurdish expansionist plans.” A report by Human Rights Watch last year outlined the rampant demolition of Arab homes and buildings—and at times whole villages—in Kirkuk and Nineveh governorate by the KRG’s forces between September 2014 and May 2016.

Such tense relations have sowed the seeds of discord and mistrust among various communities, and hence, have obstructed the normalization and the nonpartisan census that were proposed in Article 140. On the one hand, what Kurds see as the normalization of demographics is perceived as Kurdification by Arabs, Turkmens, and Christian minorities. On the other hand, after the recent takeover by Iraqi forces, Kurds now claim that Shia militias are undertaking sectarian demographic engineering. Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim recently called on Baghdad to reverse demographic changes under the KRG-controlled areas, reminding the country of the dramatic decline of the Turkmen population in Kirkuk.

There is no doubt that massive numbers of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) to and from Kirkuk will complicate the effort to conduct an impartial census and referendum on the final status of the area. According to the Displacement Tracking Matrix by the International Organization for Migration—which gathers one of the largest dataset on 3 million IDPs in Iraq—more than 500,000 Iraqis fled to Kirkuk governorate at the height of the IS crisis. The current number of IDPs in the governorate is over 380,000, which constitutes more than half of total IDPs, or 672,000, within the disputed territories. Since 2014, more than 97,000 IDPs throughout Iraq have come from the Kirkuk governorate; there has been only minimal return, with just a few thousand, which is the lowest figure compared to other Iraqi regions. In the disputed territories, the Kirkuk governorate hosts the largest number of IDPs residing in private settings (including rentals), instead of camps or critical shelters—a pattern that raises concerns about long-term demographic shifts.

Limits of the Current Turkish-Iranian Deal

If Irbil and Ankara find common ground over Kirkuk, Turkey may choose to diverge from Iran on a number of issues in the near future. Ankara has been concerned about the growing influence of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), also known as the Shia militias, to the extent that Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called the group a “terrorist organization.” Potential troubles to derail Ankara-Tehran relations include 1) Turkish military forces in Bashiqa, 2) the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) presence in Sinjar and other disputed territories, 3) the PMF’s expansion of influence in the Turkmen city of Tal Afar and Sunni Arab towns in the Nineveh governorate, and 4) Sunni leaders’ demands for local autonomy.

In a widely circulated YouTube video, an eminent PMF fighter—known by his nom de guerre “Abu Azrael”—recently threatened to “pop Turkish soldiers in the head,” referring to Turkey’s military station in Bashiqa, near Mosul. Similar threats were made by the Badr Corps, a major PMF faction that has close links to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), in the past two years. The Bashiqa camp where the Turkish military trains Sunni Arabs, Turkmens, and some Peshmerga forces has sparked controversy and tensions between Ankara and Baghdad. Last year, following the Turkish parliament’s vote to extend the deployment of Turkish troops up to 2,000 soldiers in Bashiqa, the Iraqi government called on the United Nations Security Council to adopt a resolution on the “Turkish violation of Iraq’s territory and interference in its internal affairs.” The KRG supported Ankara over Baghdad in this dispute. It is very likely that those PMF leaders who compete for Shia votes in the 2018 Iraqi elections will raise the issue in a nationalist zeal to undermine Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. If Abadi loses the election to a hardliner in the mold of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, Ankara-Baghdad relations may get tense.

A potential Ankara-Irbil realignment may encourage better relations between Tehran and PKK forces in the disputed territories, primarily in Sinjar. Having agreed to curb the PKK’s influence in the Yezidi region after the IS threat, Turkey and the KRG conducted military operations in Sinjar. Shia militias, however, have developed good relations with the PKK. Still, for Iran, the PKK is not a trusted partner; the PKK’s Iranian offshoot, the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK), threatens security in Iranian Kurdistan. Yet, since the 1990s, Iran has maintained some level of relationship with the PKK as a strategic card against Turkey. The current Ankara-Tehran embargo against the KRG restrains Iran-PKK relations; however, Iran would respond to Turkey with the PKK card if Ankara favors Irbil over Baghdad in future negotiations.

Another concern for Turkey will be the future operations of Shia militias in the disputed territories where Sunni Arabs and Turkmens constitute a majority. Although Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr recently ordered his militia, Saraya al-Salam, to retreat from Kirkuk, other PMF factions have increased their control in the region. In the Nineveh governorate, the Turkmen city of Tal Afar—once a garrison city of the Ottomans—has become a flashpoint of competition between Turkey-backed local groups and Shia militias. Further complicating Ankara-Tehran relations is the Sunni Arab leaders’ demand for local autonomy, which was supported by Turkey. The Nujaifi family, Turkey’s primary ally there, envisions a federal region for Nineveh governorate, divided in six to eight districts to reflect their ethnic/religious composition, such as Tal Afar for Turkmen, Nineveh Plains for Christians, and Sinjar for Yezidis, etc. Atheel al-Nujaifi, the former governor of Nineveh, advocates for a referendum in these districts on whether they would join the Kurdistan or Nineveh regions. For Nujaifi, “…Arabs, Kurds and other groups in Nineveh Plains should sit down and discuss the post-ISIS Nineveh…” to increase leverage against the central government. Nujaifi, however, is unable to rally most Sunni leaders behind him, and thus, such proposals for local autonomy put Ankara in a difficult position vis-à-vis Baghdad.

Washington’s Way Forward

Recent developments have sparked intense debate in Washington. Critics of US acquiescence to the Iraqi forces’ advance include Senator John McCain, who penned a New York Times op-ed to indicate his support for the Kurds. Most career diplomats who support Iraq’s territorial unity, however, believe that the developments will bring more good than harm to US interests as Abadi gains popularity and strength.

The present crisis shows that ignoring the root cause of the problem—i.e., the issue of disputed territories—will only bring further hardships in post-IS Iraq. Internal divisions within the KRG now pose a challenge for Washington in de-escalating further conflict in the disputed territories. Without a unified leadership, Irbil will not be able to present a Kurdish perspective for future prospects in Kirkuk and the Nineveh region. Baghdad will surely exploit Irbil’s negotiating weakness, but the most likely scenario is that no serious road map will be created regarding the disputed territories. Thus, the immediate crisis will be postponed once again at the expense of a bigger wave of future crises.

By offering help to the KRG to put its house in order, Washington may ensure the creation of healthy channels of communication between Irbil and Baghdad. An imminent confusion, for example, stems from the rivalry between Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani and KRG Security Council Chair Masrour Barzani. Although Nechirvan Barzani has assumed most powers of the presidency until the June 2018 elections, he lacks authority over the Security Council and the Peshmerga, which is under Masrour Barzani’s command. Last week, Masrour Barzani declared that his security forces would fight to the death rather than allow Iraqi troops to control the Fish Khabbour border crossing between Turkey and Syria—whereas Prime Minister Barzani supported a negotiated deal. As PMF leaders are now embroiled in a bitter rivalry with Abadi, there are multiple actors in play regarding both Baghdad and Irbil, which would complicate the negotiations over disputed territories.

Moreover, Washington needs to ensure that the KRG’s parliament will be functioning and the parliamentary elections will not be postponed once again. Despite stepping down as president, Masoud Barzani remains as the head of the High Political Council, a parallel structure of the government that has no accountability to parliament, whose function is defined as follows: “to protect the stability of Kurdistan from any type of threat.” Such conditions galvanize the Kurdish opposition, which calls for the resignation of the current government and establishment of a “national salvation government” that will ensure broader representation. Facing a potential financial crisis, the KRG may fail to pay salaries to public employees once again and could trigger mass demonstrations throughout Kurdistan. Thus, Washington’s support of the KRG’s stability should focus on long-term institutional reforms including political accountability, economic resilience, and transparency in the oil sector.