Introduction

Discoveries of natural gas since 1999 in deepwater basins located in the Eastern Mediterranean offshore Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and Turkey created excitement for three main reasons. First, the gas fields are located close to the European Union (EU), which has struggled to diversify a market that was long dominated by Russian supply. European hopes have risen over the possibility of an undersea pipeline to deliver gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Greece and Italy.

Second, one of the countries in whose waters gas was discovered is Israel, previously a net gas importer that in the space of a decade became a net exporter. Israel and the United States have viewed Israeli gas as a tool to create economic links to surrounding countries and to integrate Israel into the region. For instance, the inclusion of Chevron, a US oil major (a “major” refers to one of the largest private oil companies), in the development of Israeli gas fields showed that international oil companies could do business in Israel without causing breaches with Chevron’s longtime Arab partners in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

Third, gas was seen as a potential catalyst to end longstanding disputes over maritime, and even land, boundaries between states bordering the Eastern Mediterranean. Demarcating such boundaries, it was thought, would establish resource ownership, which, in turn, would reduce investment risk sufficiently to allow capital to flow. Unlocking natural gas profits, it was hoped, would create incentives for antagonist nations to solve territorial disputes. Ending the Turkey-Greece dispute over the division of Cyprus, dating to 1974, would be the big prize.

In some ways, the injection of Eastern Mediterranean gas into the regional political economy has been a success. Since the beginning of this century, aggregated reserves of some 80 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) have been discovered, and subsequent increases in production have also been impressive. Egypt and Israel have increased their production since the early 2000s. More gas is scheduled to come on stream in 2026, with the first production in Cyprus possible by 2027.1

Importantly, exported cargoes of liquefied Egyptian and Israeli gas have helped cover the EU’s loss of Russian gas since the EU reduced imports it in the wake of Moscow’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. And some of the hoped-for “gas diplomacy” has gone forward, including the 2022 US-brokered agreement demarcating the maritime boundary between Lebanon and Israel. Israel has also succeeded in developing energy export ties with neighboring Egypt and Jordan that have withstood Israel’s post-October 7 wars against Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, and Iran.

Even so, the initial excitement about anticipated peace and other regional dividends from gas diplomacy now appears naive. Amidst Israel’s wars in Gaza and Lebanon and Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping—which have required the re-routing of some liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipments2—the onset of East Mediterranean gas production has done little to calm regional conflicts or to bring adversaries closer.

Furthermore, the envisioned undersea gas pipeline between Israel and the EU has not secured the required financing, and lobbying for that purpose appears to have reached a dead end.3 The only facility to move Eastern Mediterranean gas outside the region are two 20-year-old LNG terminals in Egypt.

This paper uses a country-by-country approach to examine the factors behind the growth of Eastern Mediterranean gas production and trading and analyzes the geopolitical and economic barriers that have prevented the basin’s hydrocarbons from helping to resolve regional conflicts or to strengthen European energy security.

Resources in Perspective

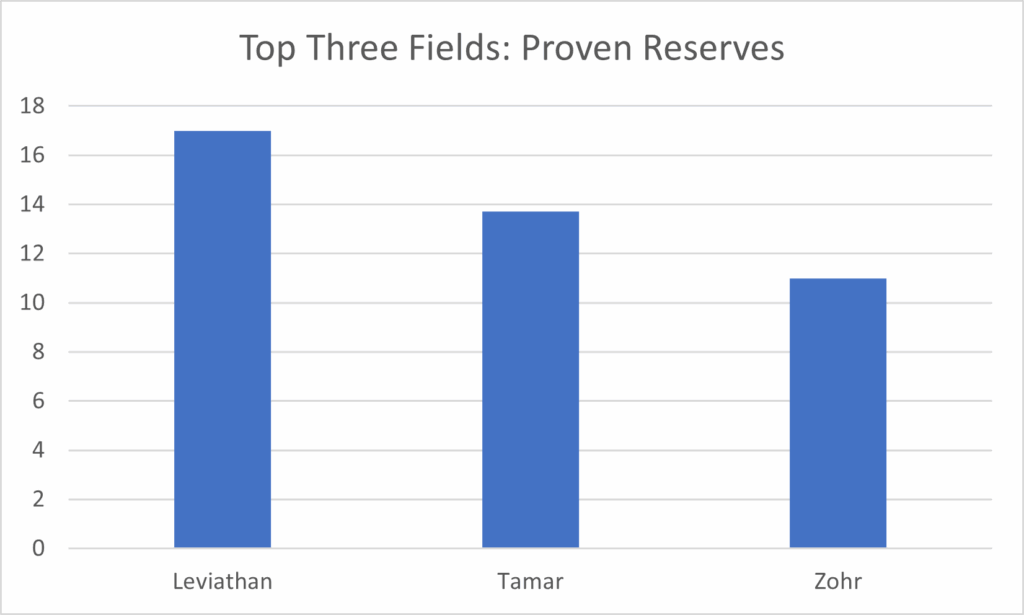

In contrast to the bigger resource basins of the Middle East, the Arabian Gulf region and the Western Mediterranean, the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean have often been viewed as population-rich, but energy-poor. That characterization is not entirely accurate, however. Egypt, for instance, is a large reserves holder, and has been an oil producer since the 1880s and a domestic gas producer since the 1960s.4 But Egypt’s recent natural gas boom came as a surprise. Texas-based Noble Energy (which Chevron acquired in 2020) discovered two large deepwater fields—Israel’s 17-Tcf Leviathan field and its 13.7-Tcf Tamar field—in 2010 and 2009, respectively, and Italian major ENI discovered Egypt’s 11-Tcf Zohr field in 2015.5

Egypt dominates natural gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean, holding nearly two-thirds of the region’s proven reserves (Table 1). Yet Egyptian reserves are less than half of those held by Algeria and just 9 percent of those held by Qatar.

| Natural Gas Reserves (Tcf) | |

|---|---|

| Qatar | 871.1 |

| Algeria | 159.0 |

| Egypt | 75.5 |

| Libya | 50.5 |

| Israel | 20.8 |

| Cyprus | 12.7 |

| Syria | 9.5 |

| Turkey | 0.1 |

| Lebanon | 0 |

Table 1: Proven reserves in selected countries in the Middle East and North Africa in 2022 (Source: EI 2024, Middle East Economic Survey (MEES) 2024, US EIA 2024/25) Note that the dearth of proven reserves in Turkey and Lebanon indicates a lack of exploration. Figure for Cyprus is based on estimates of discovered fields reported in MEES.)

Figure 1: The top three gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean: Israel’s Leviathan and Tamar, in comparison with Egypt’s Zohr. (Source: Author, citing data from MEES, “Zohr Slips to East Med No.3 With 11tcf 1P Reserves,” March 15, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2050/articles/63126)

Egypt also leads in gas production, with more than double the output of Israel in 2024, 4.6 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) versus Israel’s 2.1 bcf/d. (Table 2) None of the other Eastern Mediterranean countries discussed in this paper produce natural gas, except for Syria, which produces only token amounts after the 2011-2024 civil war devastated its previously robust oil and gas sector. Several recent discoveries in Cyprus are expected to be brought onstream in the coming years, with first production from the 3.1 Tcf Cronos field as soon as 2027.6

Regional trading of natural gas, which is dependent on the development of midstream infrastructure, is still emerging. Egypt is the only Eastern Mediterranean country with LNG export capacity, while cross-border pipelines handle a modest trade between Israel and Egypt, and export even smaller amounts to Jordan and Syria.7 (Fig. 2) Libya and Algeria operate subsea export pipelines to EU countries, but their Eastern Mediterranean neighbors do not.

| Natural Gas Production 2024 (bcf/d) | |

|---|---|

| Qatar | 17.31 |

| Algeria | 9.14 |

| Egypt | 4.59 |

| Libya | 1.38 |

| Israel | 2.07 |

| Cyprus | 0 |

| Syria | 0.26 |

| Turkey | 0.03 |

| Lebanon | 0 |

Table 2: Egypt and Israel were the only gas producers of note in the Eastern Mediterranean in 2024. Note figure for Turkey is for 2022. (Source: Energy Institute (EI) Statistical Review 2025; Turkey figure is from US Energy Information Administration 2023.)

Figure 2 (Source: US Energy Information Administration 2025)

EGYPT

As noted, Egypt is the region’s largest gas producer, consumer, and reserves holder in the Eastern Mediterranean. It is the region’s most populous country—at 116 million—and its most important exporter: Egypt is the only country in the region with ability to import natural gas from neighboring countries and to re-export it as LNG. It holds natural gas liquefaction capacity of 12.7 million tons per annum (mtpa) at its two LNG export facilities, one located in Damietta in the eastern Nile delta, and the other at Idku in the western Nile delta. (Table 3) As such, Egypt is the “gas hub” of the Eastern Mediterranean—and will remain so until pipeline capacity is built elsewhere or another regional LNG export facility begins operations. As of mid-2025, however, such developments appeared unlikely.

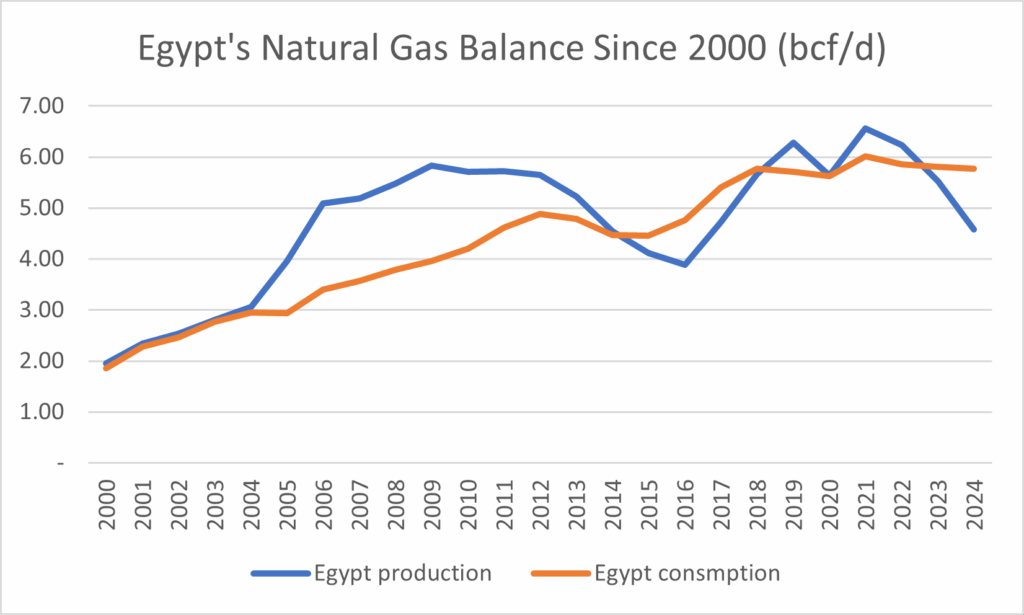

Egypt has also succeeded in attracting numerous investments from international oil companies (IOCs), which have leased exploration and production blocks offshore and made several discoveries. In 2024, Egyptian gas production averaged 4.6 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d)— but it consumed 5.8 bcf/d, meaning that the country was a net importer of gas in 2024.

Figure 3: Egypt’s domestic consumption has overtaken domestic production for short periods, resulting in net imports, as in 2023-24. (Source: EI 2025.)

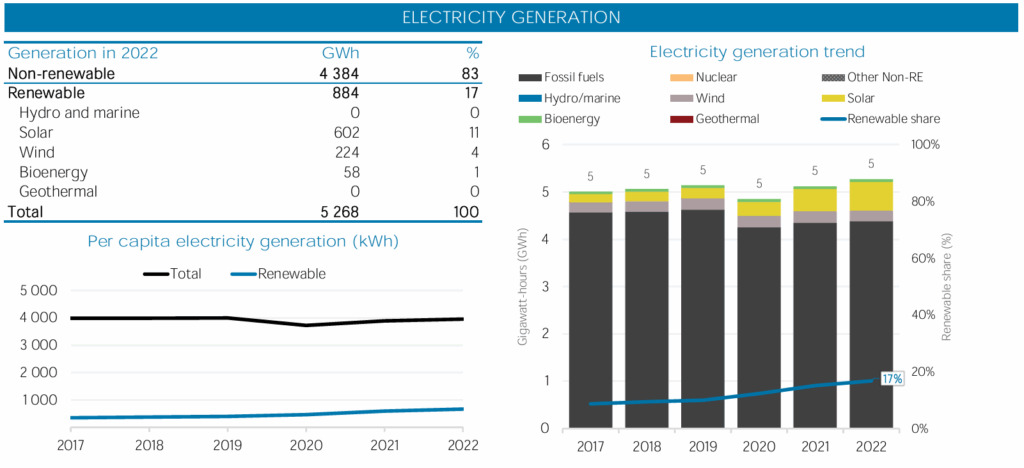

As these data suggest, by diverting gas into the domestic market, Egypt’ rising domestic demand has become a key hurdle to exports. As a result, Egyptian LNG has been an on-again, off-again business that has rendered liquefaction capacity at Damietta and Idku underutilized for long periods. A large source of demand stems from increased domestic consumption of electricity, which is subsidized by the state.8 Egypt has pledged to eliminate consumer subsidies and has embarked on a capital investment program to address this demand, constructing gas-fired power plants as well as substantial clean capacity in the form of renewables—solar and wind—and 4.8 GW of nuclear power generation (still under construction in 2025).9 Egypt’s gas consumption challenges have led it to import natural gas from Israel that is both consumed in the domestic market and, when supplies allow, re-exported as LNG.10

| Project | Location | Ownership | Nameplate Capacity (BCF/Y) | Nameplate Capacity (MTPA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian LNG T1 | Idku (Alexandria) | Shell 35.5%, Petronas 35.5%, EGPC 12%, EGAS 12%, TotalEnergies 5% | 173 | 3.751 |

| Egyptian LNG T2 | Idku (Alexandria) | Shell 38%, Petronas 38%, EGPC 12%, EGAS 12% | 173 | 3.751 |

| SEGAS LNG | Damietta | ENI 50%, EGAS 40%, EGPC 10% | 240 | 5.203 |

| Total | 586 | 12.705 |

Table 3: Egypt’s liquefaction capacity (Source: US Energy Information Administration 2023.)

Two cross-border pipelines enable such trading. The Arab Gas Pipeline (AGP), and Arish-Ashkelon pipeline, which runs from the northern Sinai Peninsula, carry natural gas between Israel and neighboring countries. The AGP is a trans-regional natural gas pipeline through which Egypt can export natural gas to Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. However, the pipeline remains underutilized because the Egyptian government prioritizes meeting domestic demand over export. The Arish-Ashkelon pipeline is a subsea branch of the AGP that was built in 2008 to deliver Egyptian natural gas to Israel. But as a result of Egypt’s domestic demand and Israel’s own gas discoveries, pipeline flows have reversed: Israel now delivers natural gas from its offshore fields to Egypt.11

Egypt exported about 173 Bcf of gas as LNG in 2023, equivalent to 3.7 mtpa, mainly to Europe and Turkey, with smaller volumes going to the Asia Pacific and to Central and South America. Egypt seasonally imports LNG to meet domestic demand, which is projected to continue growing.12 As further domestic shortages are likely, Egypt may require increased deliveries from Israel and perhaps also from Cyprus.

In the future, Egyptian gas trading may be augmented by imports and exports of electricity. Egypt is currently building a 3 GW high-voltage direct current (HVDC) link to Saudi Arabia, which would allow two-way power trading.13 Greece is considering a cross-border power link with Egypt. The GREGY Interconnector would connect Egypt to Greece via undersea HVDC cable, although a final investment decision on the project has not been reached.14

Egypt aims to increase renewable sources to 42 percent of total capacity by 2035, up from 20 percent in 2022, primarily by expanding solar and wind power to offset natural gas.15 The nuclear power plant under construction with Russian financing is expected to reach full capacity by 2030, which would add 4.8 GW of clean power generation capacity.16

Complicating Factors

Egypt’s position as the chief regional energy trade hub has been undermined by three main challenges. The first is Israel’s post-October 7 regional military campaigns, which have disrupted exports to Egypt. In 2023, for example, the Gaza war caused a one-month shutdown of Israel’s offshore Tamar field, cutting exports to Egypt and highlighting the potential for future disruptions. During the Gaza war, attacks by Yemen’s Houthis on ships passing through or near the Red Sea have disrupted an important trade route, severely reducing Egypt’s transit fees from Suez Canal passage.17 During Israel’s June 2025 war with Iran, Israel also stopped production at its Leviathan and Karish fields, once again sharply reducing exports to Egypt.18

Second, Egypt’s offshore Zohr gas field has undergone a downgrade in its reserves and a decline in production due to technical and economic challenges.19 Problems at Zohr are a major reason behind falling natural gas production in Egypt, leading to increased reliance on imports and causing power outages when imports have been unavailable or insufficient.20

A third challenge is, as mentioned, the growing demand for power within Egypt, which is diverting natural gas into the domestic market and extending the duration of periods in which Egypt has no exportable gas surplus.21 Consumer subsidies are one reason for surging domestic power use: prices remain below the government’s cost of provision. As a condition for its 2024 $8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, Egypt is supposed to gradually reduce consumer energy subsidies.22 If fully implemented, subsidy reform would help slow growth in demand for power and gas. But reforms that are not accompanied by measures to soften the economic impact on citizens could trigger popular unrest, and for this reason the Egyptian government is cautious about carrying them out.

Since Eastern Mediterranean gas is likely to pass through the Egyptian market no matter where it is produced, Egypt’s struggles pose a risk for foreign investors operating beyond its borders, including for firms exploring and developing the Israeli and Cypriot offshore fields. Risks to investors are implied by the state-owned Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation’s (EGPC) losses in selling natural gas to the Egyptian power sector at the fixed price of $4 per MMBtu, which is less than the price that EGPC pays to source much of its gas. EGPC’s payments range from a low of $2.65/MMBtu for onshore domestic production to $6.20 for ENI’s Zohr production, $6.50 for gas imported from Israel, and $10/MMBtu—or even higher—for spot market LNG cargoes (short-term market) in 2024.23

EGPC’s losses while selling gas to the state power sector are mirrored by the power sector’s loss-making sales of electricity to the Egyptian public. For this reason, IOCs operating in the Eastern Mediterranean remain wary about becoming dependent on selling gas to Egypt, whether or not the gas reaches Egyptian liquefaction terminals.24 In addition, Egypt has a history of contractual revisions and even breaches during periods of political unrest. Following the 2013 military coup, for example, the Egyptian government was more than $7 billion in arrears in payments to foreign oil companies. Egypt did eventually repay its outstanding debts, which helped foreign investors regain confidence, but the possibility of such future disruption likely remains in investors’ minds.25

Israel

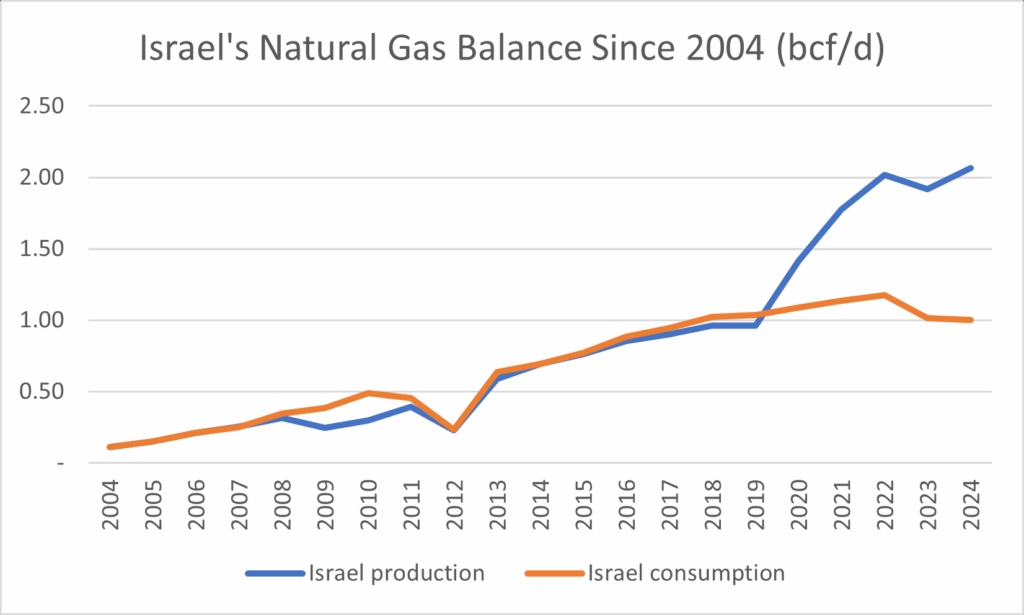

Assumed in the past to have little in the way of hydrocarbon resources, Israel has in short order become the second-largest natural gas producer in the Eastern Mediterranean after Egypt. Israel’s main offshore fields were discovered by Noble Energy and acquired by Chevron when it purchased Texas-based Noble in 2020. Chevron, operates the two largest producing fields, Leviathan and Tamar. (Israeli firms also hold stakes in these fields.)

Israel’s population of 7.5 million is small enough that it can use gas to generate 71 percent of its electricity (and to replace most domestic coal) while retaining a surplus to export. Just under half of Israeli gas production was exported in 2024.26 (Fig. 4) The fact that energy consumption is relatively low in the Occupied Palestinian Territories—just 4,000 kilowatt-hours per capita per year, versus 34,000 kWh per capita inside the Green Line—also means that Israel has more gas to export.27 Israel sells small amounts of electricity to the 3.3 million Palestinians in the West Bank and, at times, to the 2 million Palestinians in Gaza.28

Figure 4: Israel became a gas exporter in 2019, with most flows going to Egypt. (Source EI 2025.)

Stranded in the Region

Despite the surplus gas that Israel produces, geopolitical, infrastructural, and market barriers constrain its ability to fully capitalize its resources. Israel has found it difficult to export gas beyond the countries on its borders, where prices tend to be lower than those in Europe, or in spot LNG markets. Israel’s involvement in regional conflicts has deterred foreign investment, and disputes among surrounding states also have hampered opportunities for long-distance pipelines that would export Israeli gas to the European market.29

Even so, Israel’s gas exports have resulted in modest political and diplomatic gains. Chevron’s 2020 acquisition of Noble Energy was a significant step in Israel’s regional integration because it demonstrated that IOCs could now invest and operate in Israel without undermining their longstanding relations with Arab governments. For many years, oil-exporting Arab countries had used their market power to discourage IOC participation in Israel, but Arab objections began to weaken as Israel signed the 2020 Abraham Accords with Bahrain, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates. As will be discussed in more detail below, Israel’s natural gas exploration helped to catalyze its 2022 maritime boundary agreement with Lebanon, a notable development considering that the two countries have no diplomatic relations.

But Israel’s main export objective, a pipeline that would deliver Israeli gas into the big EU market via Cyprus and Greece, has gone unrealized. The project is no longer under active consideration due to technical challenges, high cost, and opposition from Turkey, which halted trade with Israel in 2024 to protest Israel’s war in Gaza.30 So far, Israel’s only EU gas connection is via Egyptian liquefaction capacity.

In light of these challenges, it appears that Israeli gas producers have shifted their focus to the states on Israel’s borders. In 2025, Chevron and its partners in the Leviathan field signed an agreement to double exports to Egypt from 0.6 bcf/d in 2024 to roughly 1.25 bcf/d in coming years, while maintaining or perhaps increasing the 0.2 bcf/d to Jordan.31

Israeli gas reaches Egypt due to a reversal of the flow of the Arish-Ashkelon (or East Mediterranean Gas [EMG]) pipeline, which now transits Israeli gas to Egypt’s Damietta LNG terminal and to be re-exported when circumstances allow. A second Israel-Egypt pipeline, the Nitzana, is scheduled to open in 2028.32

Egypt’s attractions for Israel include the capacity at its LNG facilities, which offer a potential avenue for re-exporting Israeli gas internationally. This LNG opportunity remains key for Chevron and its Israeli partner firms given the demise of EU-directed pipeline discussions.

As for Jordan, Israel exports gas to the Hashemite Kingdom via two pipelines, the circuitous Arab Gas Pipeline and the more direct Israel-Jordan Gas Pipeline.

Israel may still seek to develop new markets to avoid overdependence on the Egyptian market. Floating Liquefied Natural Gas (FLNG) had been broached as a potential option to diversify end users such as utilities and large manufacturers, but that proposal reportedly has been dropped for security reasons. Instead, Chevron and its partners have focused on expanding less-exposed undersea pipeline connections to Egypt and Jordan.33 Permanently moored FLNG ships would be at risk of attack during regional conflict.34 In summary, moving Israeli gas out of the region has been difficult without Egypt’s role.

Cyprus

The third-most promising hydrocarbon developments in the Eastern Mediterranean have taken place in deep water off the southern shore of Cyprus, a politically divided EU member state. Cyprus’s 1974 partition into north and south remains in place, with the lower two-thirds of the island under control of the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus and the northern third governed as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a de-facto breakaway state recognized only by Turkey.

IOCs including ExxonMobil, TotalEnergies, ENI, and Chevron recently discovered offshore natural gas fields that could help Cyprus wean its power generation sector off costly and dirty oil-based fuels35 (Fig. 5). Cyprus’s population of just 1.4 million—including the 400,000 residents of Northern Cyprus—suggests small domestic needs. Thus Cypriot gas discoveries appear large enough to position the country as a modest exporter.

Cyprus’s hydrocarbon investment potential, like that of Israel, is undermined by ongoing geopolitical challenges, however, especially the island’s unresolved partition and disputes—mainly with Turkey—over sovereignty of maritime zones. The so-called Cyprus question not only hampers investment in and around the island but also damages the investment environment for the entire Eastern Mediterranean region because of Cyprus’s central location there. Cyprus’s extensive, though not yet delineated, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) effectively blocks exploration in disputed areas as well as gas or electric power transmission that would transit Cypriot waters.36 The EEZ is the extension of the Republic of Cyprus’s sovereignty into the surrounding waters. Because the Republic’s maritime borders are not yet agreed upon by Turkey or the TRNC, companies are wary about exploring, or even running gas pipelines or power lines below, these waters. A political resolution that addresses who has sovereignty in which parts of the waters off the coast of Cyprus would ease risks of foreign investments.

Other factors also have made oil majors hesitant about Cyprus. These include the high cost of exploring deep water far from shore off the cost, of moving any discovered hydrocarbons to market, and the lack of gas and LNG infrastructure on the island. Cyprus has proposed building on-island facilities? to distribute some gas domestically and market some internationally, but in the meantime, developers are looking for an export outlet. The preferred option appears to be Egypt’s Damietta LNG plant, where spare liquefaction capacity is available.37 By routing sales through Egypt, however, Cyprus (like Israel) relinquishes control over the gas and exposes itself to risks of requisitioning by the fast-growing Egyptian market, where state-fixed prices are lower than those in Europe.

Also dampening enthusiasm for Cyprus LNG is the possibility that, as in Egypt, gas production may not be sufficient to guarantee constant LNG exports over the long term. Intermittent use of liquefaction capacity would be an inefficient use of investment capital, lengthening the period required to recoup investment outlays. All these factors have weighed upon Cyprus’s ability to fully develop its natural gas reserves.38

Figure 5: Most of Cyprus’s power is generated by burning fuel oil. (Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), “Cyprus: Europe Renewable Energy Statistical Profile 2024.”)

Cyprus Discoveries and Prospects

IOCs have made a string of recent discoveries in Cyprus’s southernmost territorial waters, near the boundaries with the Egyptian and Israeli zones. The deepwater finds include the Cronos and Zeus fields discovered by Eni and TotalEnergies in 2022, with reserves estimated between 4.5 and 5.5 Tcf. The Glaucus field was found even further offshore by ExxonMobil in 2019, with an estimated 3-4 Tcf of reserves.39 Earlier fields like Aphrodite (2011), 100 miles off the Cypriot coast and the largest discovery yet, along with the smaller Calypso field (2018), laid the groundwork for Cyprus’s energy ambitions.

Despite these robust discoveries, Cyprus’s gas fields have been stuck in the early stages of development, and large-scale production has yet to start. ENI has fast-tracked work on the Cronos field, and has sought to connect it to Egypt’s nearby Zohr field, 40 miles away, which ENI also operates. That “tieback” could be completed relatively quickly. Zohr is itself tied back to Egyptian onshore infrastructure by an undersea pipeline with sufficient spare capacity due to its slumping output.40

Chevron-operated Aphrodite is the largest of Cyprus’s gas fields but has been fraught by disagreements over infrastructure. Chevron has proposed a production plan involving what it describes as a “cost-effective” 150-mile tieback pipeline to Port Said in Egypt, which was approved in February 2025.41

| Cyprus Natural Gas Discoveries (Tcf) | |

|---|---|

| Aphrodite | 3.5 |

| Cronos | 2.5 |

| Glaucus | 3.2 |

| Zeus | 2.5 |

| Calypso | 1 |

| Estimated Total | 12.7 |

Table 4 (Source: MEES 2025)

The Self-Harm of Perpetuating the ‘Cyprus Question’

Cyprus-Turkey tensions in the oil and gas sector derive from conflicting claims over maritime boundaries and resource ownership. Turkey recognizes neither the Republic of Cyprus nor Cyprus’s claims to its EEZ, and opposes Nicosia’s right to make investment decisions and lease exploration blocks on the basis that this would harm the interests of Turkish Cypriots. Turkey has long asserted its rights to significant portions of Cyprus’s EEZ claim, arguing that they fall within its own continental shelf or belong to the TRNC.42

Turkey has repeatedly disrupted Cyprus’s attempts at oil and gas exploration and development, including by sending drilling ships and naval escorts into contested waters to block Cyprus’s licensed operators from conducting exploration and development activities. In some instances, Turkish naval forces have even physically obstructed Cyprus-contracted exploration vessels.?43 Such interference has caused significant delays in developing key fields such as Aphrodite and Calypso.

Numerous proposals for arbitration or third-party mediation and two UN-led proposals for resolution have failed to bring an agreement to end the island’s division.44 The diplomatic impasse extends to regional energy cooperation. Turkey continues to disrupt Cyprus’s attempts to develop its natural gas resources, and Cyprus, in turn, has created alliances with regional partners—including contracting with the state energy company in Qatar—to counter Turkish claims?.45 Notably, Cyprus is a member of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), a regional organization promoting dialogue and cooperation around natural gas development, but Turkey is not; the EMGF excludes Turkey from its joint infrastructure projects.46

The Cyprus conflict remains a major roadblock to connecting Europe to the Eastern Mediterranean. The dispute damages Cyprus’s export options because it excludes any tieback from Cypriot fields to the Turkish mainland, which lies closer to most of Cyprus than Egypt does. But it also blocks access to the lucrative European market via the Europe-bound gas pipelines transiting Turkey. Solving the Cyprus question could open the way for robust trade links between Europe and Cyprus, as well as with Israel and perhaps others.

Turkey

Turkey is a powerbroker in Eastern Mediterranean gas, primarily because it can preserve its privileged access to the EU market by blocking rivals. Turkey produces very little natural gas of its own, but is a significant importer and a vital transit country for gas produced in Central Asia, Russia, and the Middle East. An extensive network of pipelines crosses its territory, including major infrastructure such as the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) from Azerbaijan, and the Blue Stream and TurkStream gas pipelines from Russia. In addition, Turkey operates five LNG-importing terminals, three of which are tankers converted to Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs). Combined, the terminals hold 2,800 bcf/y (approximately 58 mtpa) of import capacity, which is well beyond Turkey’s domestic gas demand of around 1,800 bcf/y (37 mtpa).47

Turkey is sometimes described as a “veto player” among Eastern Mediterranean gas producers due to its actions obstructing oil and gas exploration and opposing potential pipeline routes, including an Israeli proposal to export its gas to the EU.48 Much of Ankara’s opposition is linked to its long-running land and maritime boundary disputes with Cyprus and Greece. As mentioned above, resolving the Cyprus question would assist in securing Turkish cooperation in exploration and subsea pipeline transit in the Mediterranean.

In the past, the Turkish government expressed interest in facilitating gas transit from Israel to Europe via a pipeline from Israel to the Turkish LNG landing facility at Ceyhan. For now, however, cooperation and investment are being held back by geopolitical ambitions and historical disputes as well as by the lack of clear maritime boundaries, economic questions that favor LNG, and the Gaza war.49

Figure 6: International oil and gas pipelines transiting Turkey (Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “Understanding the Energy Drivers of Turkey’s Foreign Policy.“)

In addition, Turkey’s ongoing exclusion from the EMGF continues to hamstring Ankara’s integration into regional energy ventures.50 Aggressive Turkish responses to Greek and Cypriot exploration have undermined Ankara’s regional standing.51 US officials have made clear to EMGF members that Turkey belongs in the gas forum and that excluding it is counterproductive. While tensions over exploration continue, they have diminished compared to the situation in 2019-2020.52 Turkey has since adopted a more pragmatic tone aimed at attracting foreign investment, including making overtures toward Greece, the United States, and the Gulf monarchies.53

Lebanon and Syria

Lebanon’s October 2022 signing of maritime boundary agreement with Israel, mediated by the United States, marked a rare diplomatic bright spot in the region. The boundary declaration ended the Lebanon-Israel dispute centered upon an 860-square-kilometer area in the Levant Basin that was the focus of a decade of negotiations involving multiple US administrations. Under the agreement, Israel retained exclusive rights to the Karish gas field, while Lebanon gained most of the Qana prospect.54 The historic accord between two countries still technically in a state of war has significant geopolitical and economic implications.

For Israel, it allowed the chance to develop a field over which sovereignty had been in dispute.55 For Lebanon, the agreement provided an opportunity to begin oil and gas exploration in its offshore waters. TotalEnergies began drilling in the Qana 1 well in September 2023. In October 2023, however, the Lebanese Petroleum Administration confirmed that Qana was dry, marking Lebanon’s second failed offshore well after Byblos-1 in 2020.56 Investor interest in the Lebanese offshore subsequently dried up as a result of Hezbollah-Israeli hostilities in 2024.

As for Syria, its nearly 14-year long civil war decimated its once successful oil and gas sector, based largely in the country’s east. Little is known about the potential for offshore resources on the Syrian coast, which has not been explored. Plans to demarcate and explore the Syrian EEZ were underway before the civil war.57 The December 2024 overthrow of the Assad regime and the onset of a new government in Damascus have triggered discussions about revival of the Syrian oil and gas industry. But with much of Syria’s territory—including most of the oil-producing areas—lying beyond central government control any revival remains distant. In the event of improved relations with Israel, Syria could become a transit state for Egyptian or Israeli gas heading to Turkey and Europe.58

Conflict in Syria and Lebanon has deterred foreign investment and damaged state infrastructure. The combination of war, internal political instability, and deep economic challenges have further eroded both countries’ ability to attract international interest, leaving energy potential untapped.

Conclusion

As these country-by-country assessments have demonstrated, diplomatic gains from gas discoveries have been modest, improving Israeli trade with Jordan and Egypt and making possible the Israel-Lebanon maritime boundary agreement. Otherwise, gas diplomacy has been insufficient to overcome the Levant’s intractable conflicts. And in at least one case, the arrival of gas exploration and production has been counterproductive, with the EMGF increasing tension with Turkey and exacerbating disputes over maritime boundaries between Turkey and Cyprus and Greece. Even so, some optimism remains for gas to catalyze an eventual solution to the Cyprus question.

War and other regional instability have reduced investor interest in the region. Majors including TotalEnergies and ENI repeatedly have faced challenges exploring off Cyprus due to Turkey’s claims over Cypriot waters and its repeated attempts to disrupt drilling. The Gaza war scuttled BP’s and the UAE’s ADNOC’s intent to acquire 50 percent of Israel’s NewMed Energy, which would have given them a sizeable stake in Israel’s Leviathan field.59 Israel’s wars in Gaza and Iran led to production shut-ins in its three main gas fields, temporarily reducing Israeli exports to Egypt.60 Finally, the military capabilities of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, although substantially degraded, remain a concern to investors in the Israeli offshore, diminishing prospects and increasing security costs for large surface facilities such as floating liquefaction or FLNG.61

In short, the main causes of conflict in the Levant remain undiminished. Even before the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023, the gas trade failed to unwind distrust between countries of the Eastern Mediterranean.62 Gas provides a rationale for some cooperation but is insufficient to solve deeply ingrained political disputes. Clashes over borders, resources, and sovereignty have merely migrated into the energy realm, raising investor risks and costs. Egypt remains the main exception, with its exposure generally limited to supplies of gas provided by Israel, which have recovered and even grown.

Finally, the resource base in the Eastern Mediterranean is of primary interest not because of the size of its reserves but because of its proximity to the EU market, and, perhaps, due to the inflated hopes that Israel’s gas could improve its regional standing. As for reaching the EU market, Algeria is a better prospect than the Eastern Mediterranean. The country lies closer to Europe, and Algerian gas already flows there via undersea pipelines and LNG contracts. And as Table 1 shows, Algeria’s enormous reserves far outstrip the offshore deposits to the east.

In sum, natural gas from the Eastern Mediterranean is unlikely to provide more than token assistance in alleviating conflict in the Middle East.

The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

1 “Cypriot Cronos Natural Gas Field to be Connected to Egypt by 2027,” Egypt Oil & Gas, July 27, 2025; https://egyptoil-gas.com/news/cypriot-cronos-natural-gas-field-to-be-connected-to-egypt-by-2027/; https://cyprus-mail.com/2025/09/05/cypriot-natural-gas-to-be-exported-to-europe-in-2027

2 https://www.bbc.com/news/business-67759593

3 Author’s interview with a US government official interviewed on condition of anonymity, February 2025.

4 Egyptian Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, “Gas and Petrol: Discovery, Search, and Production,” (undated); https://www.petroleum.gov.eg/en/gas-and-petrol/discovery-search-production/Pages/Petroleum.aspx

5 https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/aug/30/eni-discovers-largest-known-mediterranean-gas-field.

6 “Cypriot Cronos Natural Gas Field to be Connected to Egypt by 2027,” Egypt Oil & Gas, July 27, 2025; https://egyptoil-gas.com/news/cypriot-cronos-natural-gas-field-to-be-connected-to-egypt-by-2027/; https://apnews.com/article/cyprus-exxonmobil-qatar-energy-natural-gas-feb8e06f039fd49f04728abad743c444

7 https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/Eastern_Mediterranean

8 chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Egypt/pdf/Egypt.pdf https://aps.aucegypt.edu/en/articles/1508/the-high-price-of-power-can-egypt-escape-rising-electricity-costs

9 “Nuclear Power in Egypt.” World Nuclear Association, 2025; https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/egypt

10 https://rbac.com/egypts-gas-and-lng-global-challenges-and-global-ambitions/

11 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Egypt Country Analysis (August 2024). https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Egypt/pdf/Egypt.pdf

12 Ibid, EIA Egypt Country Analysis

13 “Saudi Arabia-Egypt Electricity Interconnection Project,” Power Technology, Sept. 13, 2024; https://www.power-technology.com/projects/saudi-arabia-egypt-electricity-interconnection/

14 “Electrical Interconnection of the Greek & Egyptian Power Systems: green transition and energy security.” GREGY Interconnector Egypt-Greece (undated) press release; https://gregy-interconnector.gr/project_en.html. See also: “Egypt Taps $Bns More In Funds To Support ‘Vital Role’ In ‘Troubled Neighborhood.’” MEES, March 22, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2051/articles/63161

15 “Egypt reaffirms 42% renewable energy goal for 2030, but urges international help.” Reuters, Nov. 12, 2024; https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/egypt-reaffirms-42-renewable-energy-goal-2030-urges-international-help-2024-11-12/

16 https://www.newarab.com/features/egypt-nears-clean-energy-goal-el-dabaa-nuclear-power-plant

17 Jim Krane, “Houthi Red Sea Attacks Have Global Economic Repercussions,” Arab Center Washington DC, April 5, 2024, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/houthi-red-sea-attacks-have-global-economic-repercussions/.

18 https://www.newarab.com/news/israels-leviathan-gas-field-resume-operations-after-shutdown

19 EIA Egypt Country Analysis https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Egypt/pdf/Egypt.pdf

20 https://www.ecofinagency.com/news-industry/2808-48235-egypt-brings-zohr-6-gas-well-online-to-slow-output-decline

21 https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=66064

22 “IMF Executive Board Completes the Fourth Review of the Extended Fund Facility Arrangement for Egypt, Approves the Request for an Arrangement Under the Resilience and Sustainability Facility, and Concludes the 2025 Article IV Consultation.” International Monetary Fund press release, March 11, 2025; https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2025/03/11/pr-2558-egypt-imf-completes-4th-rev-eff-arrangement-under-rsf-concl-2025-art-iv-consult. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/7/25/egypt-raises-fuel-prices-to-lock-in-imf-loan-tranche#:~:text=The%20new%20prices%20will%20take,poverty%2C%20according%20to%20official%20figures.

23 “Egypt Hikes Electricity Prices in Bid to Unlock IMF Cash.” MEES, Sept. 13, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2076/articles/63768. Also: “IMF Chief to Visit as Egypt Threatens To Stall On Reforms.” MEES, Oct. 25, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2082/articles/63888

24 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023.

25 https://www.arabnews.com/node/2584351/business-economy

26 “Israel country page,” International Energy Agency, 2025; https://www.iea.org/countries/israel/natural-gas

27 “Energy Use per Person: Palestine and Israel.” Our World in Data, Accessed March 6, 2025. Data for Israel is for 2023, and 2021 for Palestine; https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/palestine

28 US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, “West Bank and Gaza Country Commercial Guide: Energy,” Oct. 6, 2023; https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/west-bank-and-gaza-energy. Also: Lauren Izso, Nadeen Ebrahim and Abeer Salman, “Israel cuts electricity to last facility in Gaza receiving Israeli power.” CNN.com, March 10, 2025; https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/09/middleeast/israel-electricity-gaza-intl-latam/index.html

29 For a longer discussion of these issues, see “Israel-Iran Conflict Exposes East Med Gas Interdependence.” MEES, July 4, 2025; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2117/articles/64668

30 Former regional US diplomatic official interviewed on condition of anonymity, February 2025

31 “Leviathan Partners Agree $35bn Israel-Egypt Gas Export Deal.” MEES, Aug. 8, 2025; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2122/articles/64779

32 Ibid.

33 “Israel’s NewMed Eyes Leviathan-Saudi Gas Sales.” MEES, Aug. 23, 2024; https://www.mees.com/2024/8/23/geopolitical-risk/israels-newmed-eyes-leviathan-saudi-gas-sales/b68c7d70-6185-11ef-80ab-57b17978ccee

34 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024.

35 “Cronos: Time for Cyprus Field to Shine.” MEES, August 1, 2025; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2121/articles/64757

36 As characterized during discussions in Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, May 2023, September 2023, and January 2024.

37 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024.

38 Ibid.

39 “Exxon Makes ‘Significant’ Cyprus Gas Find, Wraps East Med Drilling Campaign.” MEES, July 11, 2025; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2118/articles/64692

40 “Cyprus Eyes Gas Riches: Cronos and Aphrodite Plans Advance, Destination Egypt.” MEES, Feb. 21, 2025; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2098/articles/64251

41 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024. Also: “Cyprus Eyes Gas Riches,” op. cit. “Cyprus to Consent to Chevron’s Aphrodite Plan Within a Month, Reports Say.” Cyprus Business News, https://www.cbn.com.cy/article/2025/1/10/815111/cyprus-consent-to-chevrons-aphrodite-plan-within-a-month-reports-say/.

42 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023 and May 2023. See also: “Turkey’s Plan for the East Mediterranean: Disrupt, Stir Up, And Provoke.” MEES, August 9, 2019; http://archives.mees.com/issues/1812/articles/57270

43 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, May 2023 and January 2024. See also: “Eni, Cyprus Talk Recent Gas Finds, EastMed Pipeline.” MEES, June 30, 2023; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2012/articles/62261

44 Foteini Doulgkeri, “Cyprus talks end without resolution, UN to continue mediation in September.” Euro News, July 18, 2025; https://www.euronews.com/2025/07/18/cyprus-talks-end-without-resolution-un-to-continue-mediation-in-september

45 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023 and May 2023. Also see: “Cyprus Hopes For Mega Exxon Elektra Find To Jolt Its Gas Sector To Life.” MEES, December 13, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2089/articles/64032

46 The members of the EMGF, which was founded in 2019 and is headquartered in Cairo, are Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine. The European Union, the World Bank, and United States are observers. See https://emgf.org/

47 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Turkey Country Analysis (July 2023); https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Turkiye/turkiye.pdf

48 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023

49 Former regional US diplomatic official interviewed on condition of anonymity, February 2025.

50 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023 and May 2023.

51 “The Eastern Mediterranean tinder box,” BBC, August 25, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53906360

52 Former regional US diplomatic official interviewed on condition of anonymity, February 2025.

53 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024.

54 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024. Also: “East Mediterranean Energy Developments,” MEES, Oct. 20, 2023;

http://archives.mees.com/issues/2030/articles/62625

55 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, January 2024. Also: “East Mediterranean Energy Developments,” MEES, Oct. 20, 2023;

http://archives.mees.com/issues/2030/articles/62625

56 S&P Global Commodity Insights. Lebanon’s Energy Future: What’s Next? https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/ci/research-analysis/lebanon-whats-next.html

57 Brenda Shaffer, “Syria’s Energy Sector and Its Impact on Stability and Regional Developments,” Issue Brief (Washington: Atlantic Council, January 17, 2025), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/syrias-energy-sector-and-its-impact-on-stability-and-regional-developments/.

58 Brenda Shaffer, “Syria’s Energy Sector and Its Impact on Stability and Regional Developments,” Issue Brief (Washington: Atlantic Council, January 17, 2025), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/syrias-energy-sector-and-its-impact-on-stability-and-regional-developments/.

59 “BP & Adnoc’s New East Med Gas JV Enters Effect: $1.9bn Arcius Energy.” Middle East Economic Survey (MEES), Dec. 20, 2024, Vol. 67, Issue 51/52; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2090/articles/64052

60 The shut-in reduced Tamar production in the 4th quarter of 2023 by 57% over the previous quarter, from just over 1 bcf/d to just under 600 million cf/d. “Egypt Squeezed as Israel Gas Exports Fall For Q2.” MEES, Aug. 30, 2024; http://archives.mees.com/issues/2074/articles/63710

61 Discussion notes, Eastern Mediterranean Gas Monetization Strategy workshop series, Middle East Energy Roundtable, Baker Institute, September 2023.

62 “Rethinking Gas Diplomacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.” International Crisis Group, Middle East Report No. 240; April 26, 2023; https://icg-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-04/240-east-med-gas-diplomacy.pdf