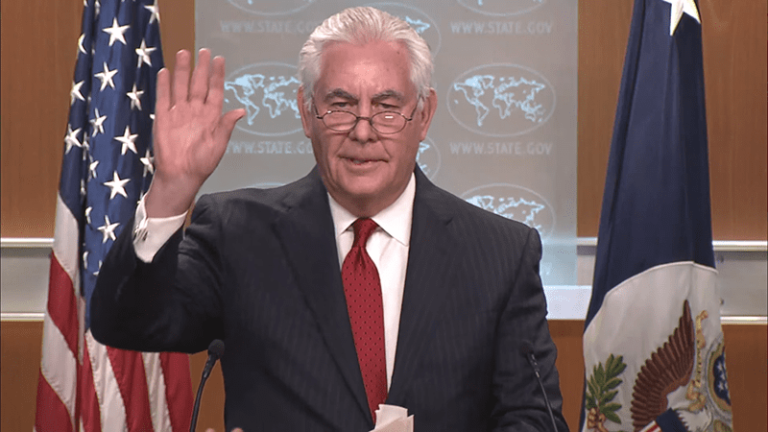

President Donald Trump’s decision to fire Secretary of State Rex Tillerson represents the climax of nearly 15 months of the president’s disparagement of the agency charting US foreign policy. While mistrust and disrespect have animated his dealings with his former chief diplomat––whose experience in world affairs was limited to the private sector ––the ouster comes at a particularly sensitive time in US foreign policy.

Would Pompeo preserve his loyalty to Trump at the expense of the State Department?

As of March 13, Tillerson delegated all his responsibilities to his deputy, John Sullivan, until he officially leaves the job on March 31. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee announced that the confirmation hearing for Trump’s nominee for secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, will be next month, without specifying a date. Hence, if confirmed, Pompeo might not take charge until the end of April or early May, if there is no holdup in the Senate. The State Department will be nowhere near ready in the short term to handle the myriad challenges awaiting the Trump Administration in the coming weeks.

Several issues and developments loom in the international arena. There are unprecedented tensions now between a key US ally, the United Kingdom, and Russia over the alleged poisoning of Russian former spy Sergei Skripal. The White House is actively planning the summit between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, and there is no US ambassador in Seoul or a North Korean expert at the State Department. The recurring three-month deadline for the Trump Administration to certify Iran’s nuclear deal is May 12 and if Trump opts to decertify, extensive diplomacy with European leaders is crucial to explain the decision and deal with its aftermath. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is expected in Washington on March 20 and will be followed by Abu Dhabi, UAE, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed and Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. Trump could potentially host the three Gulf leaders in a reconciliation summit in Camp David this May to resolve the ongoing crisis in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The much-anticipated Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative is expected to be announced soon, and US diplomacy is desperately needed to save a plan that could well be dead on arrival.

The State Department’s underlying problems predate Tillerson’s firing. Fully 60 percent of high-ranking career diplomats have left the State Department since Trump took office and applications to join the US Foreign Service have dropped by half. John Sullivan, who is now acting secretary of state, has no prior diplomatic experience and is the only top leader left at Foggy Bottom. Sullivan also serves as deputy secretary for management and resources, hence he will be overwhelmed in the coming weeks by management of the daily operations of the State Department. Last month, Undersecretary for Political Affairs Thomas Shannon—the third highest-ranking officer in the department— announced his retirement from a key position that oversees the department’s six area bureaus. Most of the senior leadership positions at the State Department are either vacant, pending Senate confirmation, or are filled on an interim basis. Undersecretary of State for Public Affairs Steve Goldstein was sacked on the same day of Tillerson’s firing because he told reporters that the secretary learned about his ouster from a tweet by the president, contradicting the White House’s version that he was informed of the decision on March 9.

The State Department has also been marginalized by the White House in budget proposals and in excluding Tillerson and his staff from key foreign policy deliberations at the White House. Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor, has played the role of de facto secretary of state, serving as the president’s point of contact with foreign leaders. The most recent marginalization of the diplomatic corps was Kushner’s visit to Mexico last week. The President’s son-in-law, whose security clearance was recently downgraded, left out the US ambassador to Mexico from his meeting on March 7 with Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto.

There will be no doubt moving forward that Pompeo would speak on behalf of Trump during his trips overseas.

Assuming he is confirmed, Pompeo would have to reckon with this reality. If the White House extends the same disregard to Pompeo and the State Department as it did to Tillerson, then it will be clear that Trump’s disdain for Tillerson was not merely personal but applies to the entire building in Foggy Bottom—which he has never visited since taking office. The question is whether Pompeo would preserve his loyalty to Trump at the expense of the State Department, or if he would use his connection to the president to salvage the institution he would lead. It is worth noting that Jeff Sessions was the main supporter of Trump before becoming attorney general; ultimately, however, he represented the interests of the Justice Department on the critical issue of investigating potential collusion between the Kremlin and the Trump campaign during the 2016 US presidential elections. While Pompeo is not expected to follow suit, his ultimate test will be finding a way to represent the interests and voice of the State Department without antagonizing the president.

Pompeo, as CIA director, has forged a strong relationship with Trump while regularly providing him with oral intelligence briefings. He should be given credit for this because Trump initially did not want to even receive these daily briefings and was, and perhaps remains, skeptical of the intelligence community. While Tillerson has often been a voice of reason in the current US administration, his periodic confrontations with Trump strained his ability to be effective. The last straw that accelerated the firing might have been his latest disagreements with the president on two critical issues: the White House’s response to the alleged poisoning of a Russian ex-spy in the United Kingdom, and Trump’s decision to meet Kim Jong-un. While Tillerson’s opinions might represent the general views of the US establishment, at the end of the day, the secretary of state serves at the pleasure of the president. There will be no doubt moving forward that Pompeo would speak on behalf of Trump during his trips overseas, and this might help Washington display a more coherent US policy on the global stage.

On the other hand, if confirmed, Pompeo will now have direct access to the president, and this will change the dynamic of the National Security Council. Tillerson was known for his close relationship with Defense Secretary James Mattis, as the two worked together to rationalize some of Trump’s most controversial foreign policy decisions. While they succeeded in keeping the United States in the Iran nuclear deal, they failed in preventing Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. What we might see moving forward is the emergence of a hawkish alliance between Pompeo, Vice President Mike Pence, and US Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley who, on Twitter, commended Trump’s “great decision” of selecting Pompeo. This new alliance might further strengthen the Trump Administration’s support to Israel and push for US deterrence of Iran across the Middle East. The Pentagon, however, will continue to push back against foreign policy decisions that might endanger US troops operating in the Middle East. While his job as the CIA director required Pompeo to be laconic in speech and writing, in the new position he would have to speak up frequently on Russia and North Korea—among other global issues on which he might not fully agree with the president.

The question now is how Pompeo would use his loyalty as he transitions from serving as a quiet spy chief to an outspoken decision-maker.

Tillerson might not be the last to be ousted from Trump’s foreign policy team. National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster could also be on his way out. The firing of Tillerson might extend McMaster’s job for an additional few months, but one can never make predictions in a presidency like Trump’s. There are already renewed speculations that Trump might fire more high-level officials such as McMaster, Sessions, and White House Chief of Staff John Kelly. Indeed, the share of the Trump Administration’s top staffers who were fired or resigned is at least 43 percent, the highest rate in 40 years, compared to Barack Obama’s (15 percent) and George W. Bush’s (27 percent) in their first two years. This turnover rate undermines not only the workings of the US bureaucracy, but also how the world perceives the stability and consistency of US foreign policy under Trump.

Once confirmed, Pompeo would have to reinvigorate US diplomacy and pick up the pieces of a demoralized State Department, regardless of the foreign policy views he might hold. Unlike Tillerson, he has already passed Trump’s loyalty test. The question now is how Pompeo would use this loyalty as he transitions from serving as a quiet spy chief to an outspoken decision-maker on US foreign policy.