Since its removal from power in 2013, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt continues to face many problems and challenges. Having always prided itself on being the most cohesive, disciplined, and united Islamist movement, the group now suffers from profound divisions and disagreements as a result of the conflict with the Egyptian regime and an internal struggle for power. For several weeks now, the group has been experiencing a rift and major disagreement at the highest level of leadership resulting from a dispute between two key leaders in the movement: Ibrahim Mounir, the acting leader of the Brotherhood, and Mahmoud Hussein, the former secretary general who controls the Brotherhood’s finances and media. The ongoing conflict and divisions raise many questions about the Brotherhood’s future and its ability to remain cohesive and united, particularly with the severe repression and exclusion it faces domestically and regionally.

Unpacking the Current Crisis

The Brotherhood’s crisis began when Mounir issued a statement on October 10, 2021 suspending the membership of six prominent leaders and referring them to investigation due to administrative and regulatory violations. The suspended leaders are Mahmoud Hussein and another five members of the group’s General Shura Council: Medhat al-Haddad, Hammam Ali Youssef, Rajab al-Banna, Mamdouh Mabrouk, and Muhammad Abdel-Wahab, all of whom reside outside Egypt. The decision came as a surprise particularly given the organizational weight and power of Hussein, who has been running the movement for quite some time. However, the suspended leaders rejected Mounir’s decision and issued a statement dismissing him from his position as the group’s acting leader. Mounir rejected the decision, considered it void, and accused Hussein and his group of trying to control the movement.

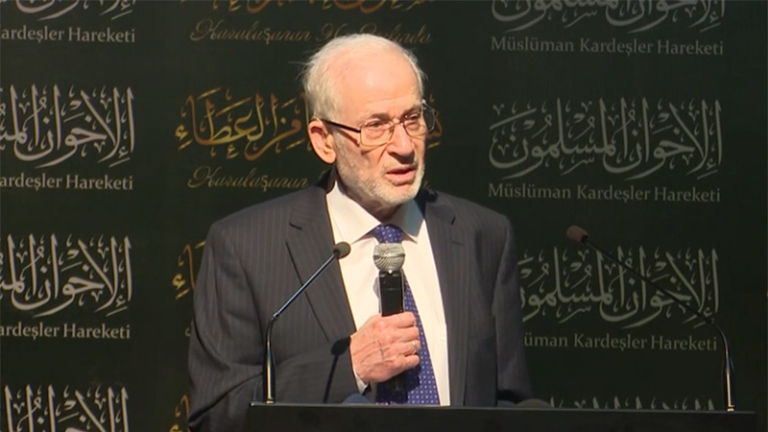

Therefore, the Brotherhood is currently divided between two factions: Mounir’s camp in London, where he lives and heads the movement as acting leader, and Hussein’s camp in Istanbul, where he and other suspended leaders have been in exile since the coup of 2013. Both claim to be the legitimate party that should lead the movement, and the membership is divided as to whom they should follow. Hussein has been in control of the Brotherhood’s branch in Istanbul where he runs its organizational activities, controls its financial assets, and supervises its media outlets. This overwhelming control has enabled him to tighten his grip over the movement during the past eight years. On the other hand, Mounir supervises the international network of the Brotherhood and enjoys good relations with foreign governments, as he has been living in the West for almost five decades. Interestingly, both leaders belong to the so-called conservative wing within the Brotherhood. For his part, Mounir enjoys more support among the youth due to his symbolic and historical role in the organization.

The Quest for Leadership

Disunity is not new to the Brotherhood. In fact, organizational and political divisions among leaders and members are as old as the movement itself, established in 1928. However, such splits have become the new norm within the Brotherhood over the past decade and particularly since the coup of 2013, which shattered the movement and created unprecedented disagreements among its rank-and-file. While past disagreements were mainly anchored in the movement’s political strategy or tactics—i.e., whether to participate or boycott elections, how to respond to regime repression, etc.—new discord emerged over the last few years among the movement’s leadership over who should run the organization, control its financial assets, manage its media outlets, and define its agenda. Mounir, who became the acting leader of the Brotherhood in September 2020 after the arrest of Mahmoud Ezzat, the former acting leader of the movement, has no real power within it. According to some of the Brotherhood’s members, it was Hussein’s idea to promote Mounir to the leadership in order to use him as rubber stamp. According to Sheikh Essam Talima, a former member of the Brotherhood and an outspoken critic of both Mounir and Hussein, the latter used the former as a cover to hijack the movement and run it for his own purposes.

New discord emerged over the last few years among the movement’s leadership over who should run the organization, control its financial assets, manage its media outlets, and define its agenda.

Three other reasons differentiate the Brotherhood’s current crisis from the previous ones. First, those implicated come from the highest level of the leadership, which is usually the party that mitigates and manages differences and divisions among members. The Brotherhood is a movement that cherishes its leadership and members tend to follow their leaders’ guidance and directions. However, this time members are torn between the two camps that are fighting to take control of the movement.

Second, the divisions among the leaders are public: each camp runs a campaign to smear and discredit the other party. As a disciplined and secretive organization, the Brotherhood has tended to contain internal differences and disputes and prevent them from getting public attention. It is also keen to maintain its image as a united and cohesive movement. At present, however, it has failed to prevent the leaders’ differences from going public and this created an outcry among the rank-and-file.

Third, this crisis comes at the time where the Brotherhood is facing unprecedented repression and exclusion from the Egyptian regime. Whereas repression in the past helped the Brotherhood to gain solidarity and enhanced cohesion among its rank-and-file, the extreme repression it has faced since 2013 has fractured it and significantly impacted its political strategy.

Below the Surface

The Muslim Brotherhood’s current crisis is a reflection of deeper structural problems from which the movement has been suffering for decades. Four key issues are worth mentioning in this regard. First, the group suffers from organizational rigidity and inflexibility, a fact that significantly impacts its ability to respond to internal and external challenges. The Brotherhood’s decision-making process is mainly conducted by a small group of leaders who control its resources and direct its activities. This inner circle is composed of the Office of the General Guide and the Guidance Bureau, which consists of 16 members; both institutions have sweeping powers at the expense of other institutions such as the Shura Council. Therefore, when the General Guide and members of the Guidance Bureau get arrested, the movement becomes paralyzed and unable to respond swiftly to political developments. That was the case after the coup of 2013 when most of the first, second, and third tiers of the Brotherhood’s leadership were arrested, sending the movement into disarray.

The leadership does not expect its decisions or actions to be questioned or challenged by members. In fact, those who dare to challenge or question these decisions are prone to exclusion and marginalization.

Second, the Brotherhood lacks clear rules of internal transparency and accountability. The organizational culture and code of values that guide the movement, which include loyalty, obedience, and blind trust in the leadership, give the latter unlimited and unchecked powers. As a result, the leadership does not expect its decisions or actions to be questioned or challenged by members. In fact, those who dare to challenge or question these decisions are prone to exclusion and marginalization, and sometimes demonization and expulsion. To that end, the Brotherhood expelled several key figures over the last few years such as the former presidential candidate Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh and dozens of young members.

Third, the Brotherhood lacks a clear vision and coherent strategy on how to respond to internal and external challenges. The leadership is exhausted because it constantly deals with everyday problems resulting from regime repression and regional isolation. It failed to develop a clear strategy for how to maintain unity during these troubling times. Not only was the Brotherhood’s leadership unable to stop the coup and to reintegrate in the political process but it has also lost much of its support both domestically and regionally.

Fourth is the alienation of the Brotherhood’s younger generation. During the last several years, promotion among the rank-and-file of the movement was not merit-based or due to members’ qualifications; rather, it was connected to their loyalty and faith in the leadership. This attitude deprived the Brotherhood from injecting fresh blood and ideas into its decision-making process, which affected its strategy and political tactics. Such an attitude has alienated young members and forced them to either abandon the movement or suspend their activities as a sign of dissatisfaction with the Brotherhood’s leadership. In fact, the movement’s political, social, and organizational losses since 2013 are enormous and it will take years to be able to regain the trust of the young members and rebuild its organizational network.

Future Challenges

Regardless of who will win the ongoing battle of leadership within the Brotherhood, and whether it is Mounir’s or Hussein’s camp, the movement is facing several acute challenges in the foreseeable future. First and foremost is the leadership’s ability to unify the movement after the many divisions and fractures it suffered since 2013. These divisions are not only ideological or political but also organizational and strategic. For the first time in decades, the Brotherhood’s leading members are scattered in more than one country, especially in Turkey, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Sudan, and Qatar. The movement is no longer in control of its members, particularly the youth who are disenchanted by the ongoing divisions. According to Haitham Said, a newly elected young leader in the Brotherhood’s office in Turkey, the main task for the new leadership is how to reengage and unite the movement.

For the first time in decades, the Brotherhood’s leading members are scattered in more than one country, especially in Turkey, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Sudan, and Qatar.

Second, the movement’s leadership is facing the challenge of how to gain the release of its political prisoners who have been languishing in prison for eight years. Thousands of prisoners are suffering under the regime of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi. The Brotherhood’s members blame the leadership for its failure in helping to end the agony of those prisoners and their families. It is true that Sisi’s regime shows no sign of trying to reconcile with the Brotherhood; however, the movement’s leadership did not take serious steps or adopt an initiative that could put pressure on the regime to release the prisoners.

Third, the Brotherhood has been operating in a significantly hostile and antagonistic regional environment; this has affected the movement’s ability to maneuver within Sisi’s regime and achieve political gains. Even those countries that provided refuge and support to the Brotherhood, such as Turkey and Qatar, began to reposition themselves with the Egyptian regime, which impacted the group’s political capabilities. Furthermore, the movement’s leadership failed miserably in mobilizing and garnering international support to end the suffering of its political prisoners and to pressure Sisi’s regime to release them.

To be sure, without addressing the deep roots of the Brotherhood’s current crisis, the movement will suffer more problems and divisions in the coming years and its future will remain uncertain.