Algeria’s Independent Election Monitoring Authority (ANIE) announced the victory of independent candidate Abdelmadjid Tebboune, in the presidential elections held on 12 December 2019. Tebboune won more than 58 percent of the vote, eliminating the need for a second round. Significantly, these presidential elections took place despite opposition from the popular movement and the mass demonstrations in Algiers and many other cities on election day.

The Electoral Process in Numbers

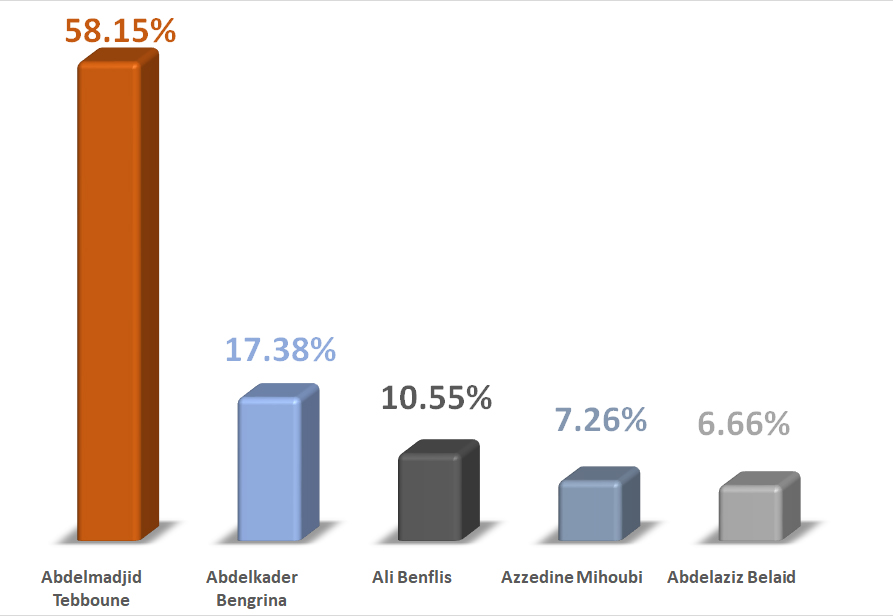

According to ANIE, the number of registered voters on the electoral lists was 24,474,161, of whom 914,308 live abroad. The domestic participation rate was 41.13 percent (9,747,804 voters) while the rate was 8.69 percent abroad, so the total participation rate turns out at 49.82 percent. The number of valid votes reached 8,504,346 and voided votes was 1,243,458, while there were 11,588 disputed votes. The elections results were as follows: Abdelmadjid Tebboune 58.15 percent (4,945,116 votes), Abdelkader Bengrina 17.38 percent (1,477,735 votes), Ali Benflis 10.55 percent (896,934 votes), Azzedine Mihoubi 7.26 percent (617,753 votes), and Abdelaziz Belaid 6.66 percent (566,808 votes). Participation rates varied by state. With the exception of the states of Bejaia and Tizi-Ouzou, which scored close to 0 percent, the rest of the states recorded participation rates ranging from 30 to 57 percent, while Algiers recorded 19 percent.

Results of the Algerian Presidential Elections (12 December 2019)

|

| Source: Prepared by the Unit for Policy Studies Studies, based on Algerian Press Service data. |

Implications of the Participation Rate

Surpassing expectations, the elections recorded an “acceptable” participation rate, despite the popular movement’s rejection. The rate is close to that of recent electoral processes in the region. The October 2016 legislative elections in Morocco witnessed a turnout of 43 percent, while the second round of the recent Tunisian presidential elections saw a turnout of around 57.8 percent. Accordingly, the turnout is unlikely to cause a legitimacy problem for the president-elect, although the clashes that occurred on polling day will have an impact.

It seems clear that a sector of Algerians believes that the political crisis has become protracted and that the presidential elections can be a step towards a solution, especially since the elections were canceled twice in a row since the resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April 2019. Therefore, it seemed that the government’s reluctance not to cancel the presidential elections for a third time in less than nine months convinced a chunk of the electorate to participate.

It seems that the popular movement’s refusal to be represented or to nominate a candidate in its name prompted other sectors of Algerian society to participate, because they believe that the movement lacks a reliable vision to solve the crisis, and that several active circles in it have deteriorated into nihilistic tendencies. The increasing appearance of moderate voices, who say that participation in the elections does not contradict the continuing pressure for additional gains, has convinced some hesitant voters to participate in the vote.

Uncontested Results

The Constitutional Council is scheduled to announce the final results of the elections between 16 and 25 December 2019,1 after examining the possible appeals against the results that can be submitted by the competing candidates. However, it is unlikely that the election results will be appealed, as both Benflis and Mihoubi had previously announced their acceptance of the results, and Benflis called for preserving national stability,2 while Mihoubi affirmed his respect for the popular will.3 Belaid, in turn, is unlikely to file an appeal against the results due to his tiny 6.66 percent margin, while Bengrina is likely to invest in his second-place spot to negotiate for important ministerial portfolios in the new government.4 The absence of contestation comes in the context of the lack of any ideological and/or policy competition between the candidates during the electoral campaign, which seemed to take place in order to promote the elections themselves rather than the manifestos of the candidates.5

How Tebboune Beat Former Presidential Alliance Candidate?

The two sides of the presidential coalition that have supported President Bouteflika’s rule through the past twenty years, the ruling National Rally for Democracy and the National Liberation Front,6 suffered a major defeat. The candidate of the National Rally for Democracy, Mihoubi, who also had the support of the National Liberation Front, came in fourth with 7.26 percent. The National Liberation Front remained reluctant to support any of the candidates until the last week, as the party’s Acting Secretary-General, Ali Siddiqui, instructed the party’s governors to call on the Front’s partisans to participate intensively and ensure the victory of Mihoubi.

This announcement of support was preceded by a state of anticipation, as it was expected that the party would support Tebboune as a member of its central committee. But the decision to support Mihoubi gave the impression that he was at odds with the party’s political bureau. Rumors spread that Tebboune was cautious about the party’s offer of support, and instead asked for support from movement’s rank-and-file not the party’s politburo. The party leadership considered this an unacceptable insult from one of the members. Beyond that, a dispute arose about the future of the National People’s Assembly, the second chamber of the Algerian parliament, which the party leadership wants to continue as it stands until the end of the parliamentary term, while Tebboune calls for its dissolution and for early parliamentary elections.7

Moreover, the appearance of Tebboune’s son a week before the elections in the dock with detainees in corruption cases, and the focus of the regime media on that, gave the impression that the state apparatus was seeking to bring him down for the sake of Mihoubi. This has created a kind of sympathy for Tebboune, who has presented himself as a technocratic statesman who stands on the edge of the partisan map that has been marginalized by the popular movement. Regardless of what appeared to be attempts to influence Tebboune’s fortunes, these measures prompted a portion of the electorate to participate in the vote, and in his favor in particular. Reports have also suggested that if Mihoubi wins, he will move towards a presidential pardon for the senior corrupt regime leaders, led by Ahmed Ouyahia, the former Secretary-General of the National Rally for Democracy. Tebboune appeared, in the eyes of a significant segment of the voters, as an independent candidate who does not enjoy the support of the National Liberation Front and the National Rally for Democracy despite his closeness to the circles of power and his many years of service in the regime.

Furthermore, during his campaign, Tebboune used simple and common language addressing national sentiments, especially when it comes to fighting corruption, Algeria’s relationship with France, Algerian sovereignty and the rejection of foreign interference in its domestic affairs, and Algeria’s regional role in the Maghreb, Africa, Mediterranean, and the Global South. He also benefited from the prevailing impression that he was a victim of corrupt officials during the Bouteflika era, because he was dismissed as Prime Minister in less than three months after his appointment, due to his call to combat corruption and for the disengagement between politics and money, as well as his presentation of himself as a victim of the establishment which sought to discredit his image from the beginning of the election campaign. Tebboune has also benefited from the prevailing impression that he has the ability to confront the remnants of the Bouteflika regime, thanks to his vast experience within government circles, and that his campaign was focused on the issue of recovering the looted money, which is a sensitive topic for the Algerian people, many of whom believe that the trials and rulings issued by the government alone are not enough and constitute purely symbolic action.8

Implications of the Decisive Victory

Although Tebboune was not the first choice of the government, the decisive first round election results are convenient. Regardless of the controversy over whether there was interference – an assumption that is not supported by sufficient evidence – going to a second round would have had potential high costs. First, the prolongation of the crisis and the absence of guarantees for the success of organizing a second round in light of the continued rejection from the popular movement. Second, the possibility of security chaos that may be hard to contain and may develop into a violent clash between those who support or reject the elections. Third, and most importantly, the results of the first session proved, as expected, that the second session would have led to the possibility of reproducing traditional polarization, with the arrival of Tebboune, member of the Central Committee of the National Liberation Front, on the one hand, and Bengrina on the other hand, representing the Islamic trend (despite not defining himself as such). This reproduced a potential confrontation between the national and Islamic currents. Therefore, it is more likely that the government breathed a sigh of relief by resolving the elections in the first round, even if its man lost.

Tebboune’s presidential test in the coming months will be in his ability to gain the confidence of Algerians in general, and the popular movement in particular, by taking a number of measures such as the release of detainees and the launch of a serious national dialogue that requires the stipulation of public freedoms, including free media, followed by a transitional period led by the president himself with the participation of the opposition. If these steps are taken, the recent elections could be a milestone in Algeria’s history.

An earlier version of this paper was published on December 16, 2019 by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies (ACRPS) in Doha, Qatar.

1 “The Constitutional Council announces the final results between 16 and 25 December,” Algerian Press Service, 12/13/2019, accessed 12/13/2019, at: https://bit.ly/2MazzXx

2 “Benflis does not confirm that he will not contest the election results and calls for preserving the country’s stability.”, Algerian Press Service, 12/13/2019, accessed 12/12/2019, at: https://bit.ly/2RSnIAY

3 “Mihoubi confirms his respect for the popular will and his support for the President-elect,” Algerian Press Service, 12/13/2019, seen on 12/13/2019, at: https://bit.ly/2EkvtYs

4 Bengrina will presumably maintain his position in the political scene by avoiding confrontation with the emerging authority after the elections. This is inherent in the voting bloc that Bengrina brought out in these elections, which can be considered an undeniable asset. In addition to the man’s history as one of the “historical” representatives of political Islam (the Brotherhood current), this voting bloc will be represented in the future government in this capacity.

5 “Algeria’s Presidential Elections: Perpetuating Polarization or a Step Toward a Solution?” Case Assessment, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 8/12/2019, accessed 12/13/2019, at: https://bit.ly/2RRUCBD.

6 Since Bouteflika was re-elected President of Algeria for a second term in 2004, the Presidential Alliance was formed from the National Liberation Front, the National Democratic Assembly, and the Peace Society Movement, before the latter withdrew in 2012.

7 See, for example: Muhammad Muslim, “Why ‘Didn’t Support’ FLN’s Tebboune?”, Echorouk Online., 5/12/2019, accessed 12/13/2019, at: https://bit.ly/2EnIm3H

8 “Bengrina hints at the release of criminals in exchange for the recovery of the looted funds”, Al-Massar News, 11/11/2019, accessed 12/14/2019, at: https://bit.ly/36yhxWK.