Twelve months of high drama in Iraqi politics finally ended on October 27, with the investiture of a new government headed by Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani. Two weeks prior, the Iraqi parliament elected Abdul Latif Rashid as the country’s president following his nomination by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) to succeed Barham Salih of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). These two events came after a year of chaos, sudden reversals, and dangerous confrontations that brought Iraq to the brink of civil conflict. However, both Iraq and its incoming prime minister face daunting challenges born of disagreements between elites and political parties, of endemic corruption and malfeasance, and of unresolved disputes between the central government and the country’s autonomous Kurdish region.

A Dramatic Political Reversal

In a move that most observers regard as a strategic blunder of historic proportions, members of the Iraqi Parliament belonging to Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s political movement submitted their resignation from the chamber in June 2022. Their list had won the largest number of seats in the country’s October 2021 elections, which entitled them to form a government with their allies, the KDP and the Sunni Sovereignty Alliance, led by Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi.

Most of the seats vacated by the Sadrists were captured by runners-up from the Iran-friendly Coordination Framework (CF), chief among them Sadr’s main nemesis, former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. With a stroke of the pen, the CF—a coalition made up of Shia parties and elements of the paramilitary Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—suddenly held 138 seats, becoming the largest bloc in parliament. The political upset was thus a victory for Shia hardliners allied with Iran and signaled the demise of the notion of a cross-sectarian, ethnic majority government, which Sadr had previously proposed.

The Sadrists’ resignation from parliament was a victory for Shia hardliners allied with Iran and signaled the demise of the notion of a cross-sectarian, ethnic majority government, which Sadr had previously proposed.

Members of the CF, mindful of Sadr’s influence over a wide segment of Iraq’s Shia population and holding fresh memories of both the Sadrists’ occupation of parliament in August 2022 and the intra-Shia confrontations that led to scores of casualties, expressed their hope that he would join them in a new, all-inclusive government. However, Sadr was adamant that he would not. These efforts at outreach revealed fissures between relative peace-makers within the CF, represented by head of the Badr Organization Hadi al-Amiri, who wanted Sadr on board, and hardliners led by al-Maliki and Qais al-Khazali, head of the Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq militia, who seized this opportunity to remove Sadr from the political scene.

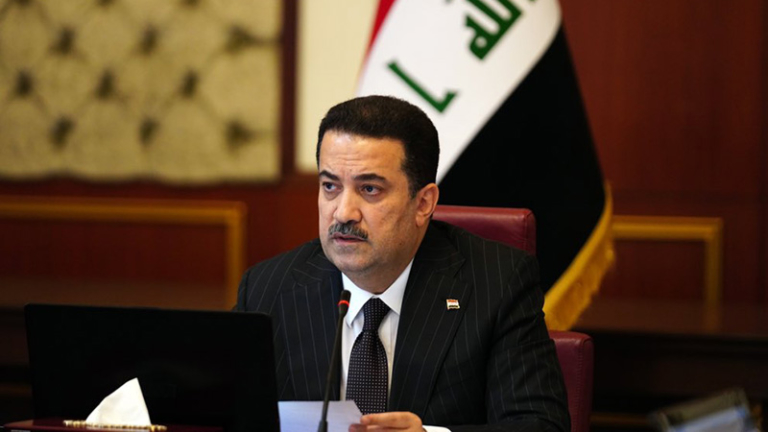

Faced with Sadr’s continued obduracy, the CF declared itself the largest parliamentary bloc and nominated one of its own, Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani, for prime minister. Sudani, an agricultural engineer, is a former member of the Dawa Party and the former governor of Iraq’s Maysan Governorate. He has also served as minister of human rights and of labor and social affairs, and is said to be close to al-Maliki.

The CF had earlier formed an alliance with the PUK and al-Azm (a small Sunni party headed by Muthanna al-Samarrai), but it needed a broader coalition to form a national consensus government and to bolster its national legitimacy. Hardliners in the CF also sought to isolate and neutralize Sadr further by including his allies, the KDP and al-Halbousi’s Sovereignty Alliance, in a national coalition. This was not easily accomplished, as the CF had previously antagonized both of these actors. Initially reluctant, the KDP and the Sovereignty Alliance eventually accepted the overtures of the Coordination Framework.

Government Formation

The CF declared the formation of a comprehensive umbrella for all parties, the State Management Coalition (SMC), with the CF at its core. This was a useful vehicle for the CF to claim that it has brought everyone into the fold. But without creating a formal agreement or a declaration of principles, the SMC remains a nebulous entity without cohesion. Unlike in their former alliance with Sadr, the KDP and the Sovereignty Alliance do not appear particularly committed to the SMC.

The CF declared the formation of a comprehensive umbrella for all parties, the State Management Coalition, with the CF at its core. This was a useful vehicle for the CF to claim that it has brought everyone into the fold.

The CF itself suffers from its own political discords. The coalition includes armed factions and civic political parties; political hardliners, moderates, and pragmatists; and powerful militia groups that have close relations with Iran and other parties that do not. The decision of whether to include or exclude Sadr further exacerbated existing tensions. Disputes over strategic ministries and posts became public, and amid the melee al-Maliki and parties representing armed militias aligned with Iran gained the upper hand.

Within two weeks of his nomination Sudani presented a cabinet for a vote in parliament. Negotiations among political parties for ministerial allocations exposed rivalries and general ill-will within the Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish camps. Within the CF, the ministry of oil was the subject of competition between al-Maliki and the head of the Fatah Alliance, Hadi al-Amiri, but eventually went to al-Maliki. Meanwhile, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq fought with Kata’ib Hezbollah over the leadership of the national security and intelligence agencies. In the Sunni camp, al-Halbousi and al-Samarrai of al-Azm fought over the ministry of defense, which al-Azm then won. The KDP and the PUK, meanwhile, argued about the number of ministries allotted to them, with the PUK contending that since President Rashid was the KDP’s choice he should not be counted against their allocation.

Although this may be routine jockeying for position, such acrimonious competition has exposed the fissures within each sectarian/ethnic group. The CF repeatedly said that it would allow Sudani the ultimate choice of ministers from lists provided to him by constituent parties, but ministries ultimately proved too valuable to be left to his independent choice, since they provide an important source of leverage and revenue for political parties, gained through nepotism, patronage, and corruption.

The 21-member cabinet voted in by parliament on October 27 included 10 CF-nominated ministers, in addition to one ministry for a Christian member of the PMF, six for the Sunnis, and four for the Kurds, of which two are still contested by the KDP and the PUK. Two critical ministers, those of finance and of interior, were chosen by Prime Minister Sudani. The biggest winners in the cabinet’s distribution were al-Maliki, with three ministries, including that of oil, and al-Halbousi, with three ministries, including that of industry. The government formation process thus reverted to the longstanding system of collective government and power-sharing (in Arabic, al-muhasasa), in which all major parties (with the exception of Sadr’s movement) have a share, and in which there is no clear locus of responsibility and therefore limited likelihood of accountability for any future failures or malfeasance.

The biggest winners in the cabinet’s distribution were al-Maliki, with three ministries, including that of oil, and al-Halbousi, with three ministries, including that of industry.

Although the infighting demonstrated the cracks in the country’s ethnic/sectarian groups, the past year’s political turmoil has resulted in a victory for Shia hardline groups and their dominance not only over moderate Shia but over the entire political process. The ascendancy of the hardliners is a victory for Iran, which has succeeded in reviving and holding together the “Shia house,” despite the absence of Sadr.

Prospects for the New Government

Prior to presenting his cabinet for a vote, Sudani submitted his proposed government program, an ambitious document that addressed every possible topic. It promised to improve public services, grow the economy, create jobs, revitalize agriculture and industry, and fight corruption. It also pledged to reduce dependence on oil revenue to 80 percent within three years. And Sudani promised to strengthen the capacities of security agencies and institutions, including of the PMF. On foreign policy, he called for balance and non-interference. But significantly, the program did not call for the immediate withdrawal of foreign forces from Iraq. An even more disturbing omission is the absence of any reference to much-needed political and institutional reform, a key demand of Iraq’s 2019 Tishreen protest movement that was also championed by Sadr.

Meanwhile, a six-page addendum to the government program titled “Political Parties’ Agreement” (and lacking party signatures) requires parliamentary elections within one year, and makes other stipulations. However, Sudani’s program makes no mention of early elections, and indeed reads as though it is at least a four-year program. It is not clear whether the extensive agreement is an integral part of the government program, and to what extent Sudani will be bound by it.

Sudani is reputed to be capable, serious, and energetic. He has the backing of the CF’s principal Shia parties and has at least been given the benefit of the doubt by other parties that contributed to forming this new government. The international community also appears well-disposed toward him. If Sudani is not thwarted by the vested interests of political parties, he can potentially achieve a great deal in a four-year term, especially in the sector of service delivery and in improving governmental efficiency. It will be to the advantage of political parties to use Iraq’s considerable surpluses to improve health services and educational facilities, to increase electricity generation, to expand job opportunities, and to raise the standard of living, especially given the staggering 31 percent rate of poverty recorded in 2021.

If Sudani is not thwarted by the vested interests of political parties, he can potentially achieve a great deal in a four-year term, especially in the sector of service delivery and in improving governmental efficiency.

Challenges will still abound. Even in non-controversial service sectors, such as electricity, Sudani will face entrenched financial and patronage interests that could impede his efforts. He will have to tread carefully if he ventures into areas that affect the power or revenues of important actors. The security sector and oil interests are cases in point. Al-Maliki fought hard to gain the lucrative oil ministry, which is the nerve center of Iraq’s finances, and big players in the CF, including al-Maliki and the PMF, are exerting pressure to control the country’s security agencies. Such a move is necessary to eliminate future challenges to their power, avoid accountability, and clip Sadr’s wings. These parties and groups may bicker over specific posts, but they will all band together to preserve their collective control over these agencies. Although Sudani succeeded in appointing his choice of interior minister, it is not clear that he will be able to prevent other security agencies from being captured by his main backers in the CF.

In his government program, Sudani pledged to “support and develop the professional capacities of the PMF and to build its institutions.” This is ominous, as it suggests that there will not be an effort to curb the growing strength and unchecked activities of Iraq’s paramilitary organizations. Combined with PMF efforts to capture state security agencies in the new government, any talk about bringing weapons under government control will be toothless. Indeed, the result may be the reverse, as militias will likely be in a position to dominate and manipulate formal security and defense agencies without check.

Sudani’s high-minded program also pledges to fight corruption. But much as his predecessor Mustafa al-Kadhimi, he can only arrest smaller fish, and is unlikely to bring to justice the larger sharks who are the real sponsors of the country’s corruption. For example, in Sudani’s first week in office, Iraqi security agencies claimed to have broken up a large oil-smuggling ring based in Basra that reportedly included army and security officers. The speed of the action raises the question of whether the move was initiated during his predecessor’s government or whether it was a trumped-up operation aimed at getting rid of unfriendly elements in Basra. In any case, oil smuggling on a massive scale can only occur with political complicity; but it will be difficult for Sudani to hold any political actors to account.

Sudani will have to handle disputes between several political players. Disagreements will quickly emerge between the federal government and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) over oil contracts and revenue distribution. Some actors in the CF have taken a hard line against the KRG on the issue of oil, and it must certainly bring no comfort to Kurdish leaders that the new minister of oil is an al-Maliki appointee. Negotiations over the oil law and the constitutionality of KRG contracts will force Sudani to walk a tightrope between KRG interests and those of CF players. Similarly, the Sunni demand for the removal of PMF forces from Sunni areas that were liberated from the so-called Islamic State and for the curtailment of the PMF’s economic exploitation of these regions will place Sudani in the difficult position of mediating between his militia backers in the CF and Sunnis who gave him their vote of confidence.

Sudani will have to handle disputes between several political players. Disagreements will quickly emerge between the federal government and the Kurdish Regional Government over oil contracts and revenue distribution.

A final challenge for Sudani will be pursuing relations with Iraq’s neighbors and with the wider region. Relations with Arab countries that were first initiated by al-Abadi were subsequently expanded and deepened by al-Kadhimi, who established diplomatic and economic ties with GCC countries, Jordan, and Egypt, and who hosted rounds of dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia. In his program, Sudani proposes strengthening these ties, but the CF is suspicious of ties with Arab countries, which they fear will undermine Iran’s (and therefore their own) political and economic interests.

Much to Accomplish, Much to Overcome

Sudani appears eager to put his own stamp on the new government, and the transition from a Sadrist-controlled to a CF-controlled regime is rapidly taking shape. Within days of his tenure, Sudani dismissed officials appointed by al-Kadhimi to security and intelligence agencies, as well as staff in the office of the prime minister. The swift and wholesale nature of the action has been called “a purge” of the allies of al-Kadhimi and Sadr. There certainly is a whiff of vengeance in these proceedings, as the sweeping dismissals have been accompanied by a CF-led campaign calling for the detention of al-Kadhimi and his officials on charges of egregious corruption. While it is too early to measure the political repercussions of the dismissals, several of the announced replacements in the office of the prime minister are associated with the PMF and al-Maliki.

The grand coalition of the CF, Kurdish parties, and Sunni parties that together formed Iraq’s government is fragile and unstable. To succeed in his self-set tasks as prime minister, Sudani must be willing to resist pressure from hardliners in the CF and to juggle the interests of several partners in the political process, but as a pragmatist he may wish to avoid confrontations. Even with the best of intentions and the greatest of effort, Sudani will have his work cut out for him.

Featured Image credit: Twitter/Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani