When President Joe Biden was sworn in on January 20th as the 46th president of the United States, America’s friends in particular hoped that his administration would take a strong moral stand against all human rights violations. His choice of Kamala Harris—as not only the first woman, but the first woman of color—as vice president also sent a message that the issue of women’s rights, which includes politically motivated imprisonment of women activists, bloggers, journalists, and/or regimes opponents, was expected to occupy a special place in the Biden Administration’s list of priorities.

Nine months later, however, there is little evidence to support these optimistic expectations. In August, eight Democratic US senators, under the leadership of Senator Bob Menendez (D-New Jersey), who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, sponsored a resolution condemning the politically motivated imprisonment of women around the world and demanding their immediate release. The resolution condemned a number of countries, including four in the Middle East—Turkey, Iran, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—for the unjust imprisonment of leading women who are considered “political prisoners,” and called for their immediate release. What these four countries have in common—in addition to being in the Middle East, having predominantly Muslim populations, and displaying varying degrees of autocratic rule—is a combination of a problematic human rights record with an equally troubling gender rights record, albeit in diverse forms and to different extents.

While the US Senate’s resolution is certainly a welcome step in the right direction, it is a small and limited one that falls short of expectations. It failed to account for these countries’ overall human rights records, including other cases of imprisonment of political opponents, especially women. It also did not recognize the political imprisonment of women in other countries in the region, including Palestinian women who were, and continue to be, behind bars in Israel. This paper will focus on the cases of women political prisoners in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, although the practice is not limited to them.

Egypt: Human Rights and Regime Impunity

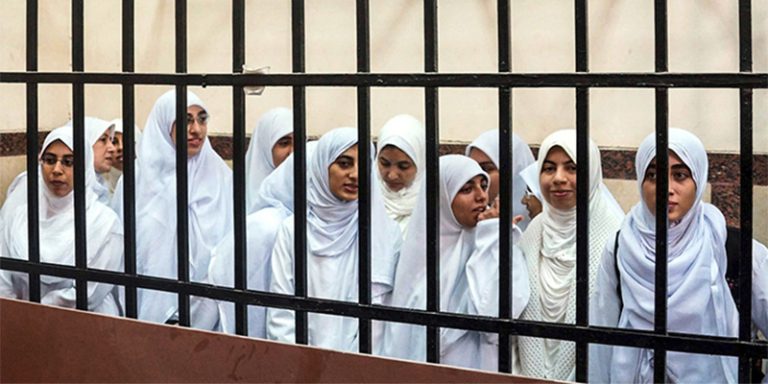

The derailment of democratization and the consolidation of authoritarian rule in Egypt, following the 2013 military coup, resulted in a severe deterioration in human rights, far exceeding the case in President Hosni Mubarak’s era. This was detected by a number of international organizations, including Amnesty International, which highlighted the broad spectrum of human rights violations in Egypt today, such as large-scale imprisonment of the regime’s opponents (estimated to be in the tens of thousands) who are held mostly in “cruel and inhuman conditions,” restrictions on human rights organizations and political parties, severe repression of the rights to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression and association, and harassment and jailing of journalists.

This wave of limitations of freedoms worsened significantly in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. The government issued new cybercrime laws to fight so-called fake news, further restricting freedom of expression and punishing anyone who shares any information that contradicts the official, state narrative about the pandemic, whether they are doctors, journalists, or critics.

One of the victims of this new wave is Sanaa Seif, an activist who was sentenced to a year and a half in prison in March under the charge of spreading false information. However, Seif, who is the sister of jailed Egyptian blogger and activist Alaa Abd El Fattah, was simply alerting the public about the dire and inhumane conditions in which her brother and other prisoners are being held, as these provide the ideal environment for the rampant spread of the virus. More importantly, her arrest could be interpreted as an official retaliation for the online campaign that she and her family launched on Facebook and Twitter under the hashtag #IWantALetter, demanding communication from her imprisoned brother to confirm his safety.

Although Sanaa Seif was the only Egyptian woman prisoner mentioned in the US senators’ resolution, she certainly was not the only woman to face this dire fate recently in Egypt. The Egyptian authorities previously detained Basma Mostafa, who reported on COVID-19; Nora Younis, from the independent Al-Manassa news website; and Lina Attallah, editor-in-chief of the independent Mada Masr website. Additionally, other women prisoners included activist and human rights defender Mahienour El-Masry, who was arrested under the charge of belonging to an “illegal organization” and was released on bail in July 2021, after spending almost a year in jail, and prominent activist Esraa Abdel Fattah, who was also released on bail in July 2021, after spending almost two years in prison with charges of “spreading false news” and collaborating with a “terrorist group.”

Violations of rights had no impact on Egypt’s cozy relationship with the West. Rather, its military regime appears to have been emboldened by unconditional support from its western allies, especially the United States.

Nevertheless, these violations had no impact on Egypt’s cozy relationship with the West. Rather, its military regime appears to have been emboldened by unconditional support from its western allies, especially the United States. Shortly after President Joe Biden praised Egypt’s role as a mediator in ending the latest Gaza war, the execution orders against 12 Egyptian dissidents were upheld, following a grossly unfair and politically motivated mass trial. Furthermore, security forces continue to enjoy total impunity over the killing of at least 900 people in the infamous Rabaa Square massacre, to the dismay of Egyptian and international human rights activists and observers.

Critics of the current human rights crisis in Egypt have always wondered why the United States is not using its leverage as the provider of $1.3 billion in military aid to the Egyptian army annually, making Egypt the second largest recipient of such assistance, after Israel. Many believe that Washington should put pressure on the Egyptian regime to reform its human rights record. Some activists—including regime opponents who remain in exile—and a number of international organizations are urging the Biden Administration to do just that, arguing that it is the only way to put an end to the escalating human rights violations against the regime’s critics, activists, and journalists, women and men alike.

Saudi Arabia: Crackdowns and Paradoxes

Saudi Arabia has always had the most conservative and restrictive agenda in the region in terms of women’s rights. It adopted a strict Salafi Islamic school of thought, Wahhabism, under which Saudi women were traditionally denied many of the rights enjoyed by other women in the Arab region such as driving and traveling by themselves.

It was not until Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), the current de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, came to power and launched his Saudi Vision 2030 for the country, allowing for a new and unprecedented margin of social freedom and openness, that some of the strict social codes started to ease. This included lifting the driving ban for Saudi women and ending the guardianship law, which had restricted their mobility, agency, and public participation.

Paradoxically, some Saudi women activists were imprisoned for simply asking for the very same rights that were included in MbS’s Saudi Vision 2030.

Paradoxically, however, some Saudi women activists were imprisoned for simply asking for the very same rights that were included in MbS’s Saudi Vision 2030. For example, the move to lift the driving ban was accompanied by an intensified crackdown on Saudi women’s rights activists who campaigned for the right to drive. Several of them were detained and faced trials, and sometimes long prison sentences, as a result of their activism, as part of this campaign.

These women included Manal Al-Sharif, who launched the popular Women2drive campaign on YouTube and documented her relentless efforts to raise awareness about women’s right to drive in Saudi Arabia. She was detained for her activism and released later. The well-known Saudi activist Loujain al-Hathloul campaigned not only for women’s driving rights but also to safeguard women’s free access to the public sphere. She was also arrested, and later released, under the condition of never discussing the experience she had behind bars. Another detainee is Mayya al-Zahrani, a women’s rights activist who was arrested amid a wave of arbitrary detentions. A group of bipartisan senators have asked the Saudi ambassador to the United States to facilitate her release.

These paradoxes, according to self-exiled Saudi activist, writer, and women’s rights defender Hala Al-Dosari, reflect a form of tokenism on the part of MbS. She points to the fact that he strives to position himself as the sole grantor of civil rights, including women’s rights, and as the benevolent ruler who can grant or deny them—while punishing any bottom-up, grassroots activism asking to secure the very same rights through public mobilization.

Israel: No US Criticism of Imprisoning Palestinian Political Activists

Although the above-mentioned US Senators’ resolution did include other countries, such as China and Belarus, in addition to the four in the Middle East, one obvious omission is the plight of Palestinian women prisoners in Israeli jails. Many of them suffer from dire and inhumane conditions and some have been arrested and tried for participating in nonviolent demonstrations. It is estimated that there are currently at least 35 women Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails, among them 11 mothers, six wounded prisoners, and three administrative detainees. They also include Khalida Jarrar, a Palestinian lawmaker, who has been in and out of an Israeli prison for the good part of six years. She was recently prevented from attending her daughter Suha’s funeral despite entreaties from local and international personalities and organizations.

Recently, some Palestinian women who have undergone the horrific experience of imprisonment in retaliation for their political activism, have attracted media attention. These include the young Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood campaigner, Muna El-Kurd, whose brief detention along with her twin brother, Mohammed El-Kurd, went viral on social media, stirring far-reaching international reactions. Likewise, the recent release on bail to house arrest of pregnant Palestinian prisoner Anhar Al-Deek, as ordered by an Israeli military court, spurred a new wave of international attention on social media while raising awareness about the largely forgotten Palestinian women behind bars.

The historically strong US-Israel relationship, coupled with an equally strong Israel lobby in the United States, mean that there is usually very little, if any, official criticism of Israel’s human rights violations against the Palestinians.

However, these are only a few examples of this wave of imprisonments, which is likely to continue as long as Israel continues to enjoy impunity regarding such human rights violations. The historically strong US-Israel relationship, coupled with an equally strong Israel lobby in the United States, mean that there is usually very little, if any, official criticism of Israel’s human rights violations against the Palestinians, including the imprisonment of Palestinian women and children.

Whenever such rare criticism takes place, usually by progressives like Palestinian-American Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan) and Somali-American Congresswoman Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota), it is mostly shunned by accusing them of using anti-Semitic tropes. This discourages vocal critics and others from voicing their concerns. It is only reasonable to expect that the continuing and deliberate neglect of Israel’s human rights violations, including the imprisonment of women Palestinian activists and/or their children, will only embolden the Israeli government to continue on the same path, while further subjugating opposition and suppressing dissent.

The Road Ahead

Moving forward, it would be essential to adopt a comprehensive approach to tackling issues of human rights in the Middle East region, one that takes into account the broader context of regional socio-political transformations and power dynamics. Importantly, it behooves the United States to pay special attention to its relationships with the different regimes and its direct or indirect impact on these regimes’ degree of accountability and transparency—or lack thereof—when it comes to human rights violations. Only then can we truly unpack the root causes of the largely timid and selective US role in safeguarding human rights, including women’s rights, in the Middle East region and beyond, and address and rectify them to chart a more credible and impactful road ahead. Until such a time, it is most likely that we will witness a continuation of all human rights violations in this volatile region.