The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has a checkered relationship with American oil companies. In the 1970s, OPEC member states pushed the likes of Exxon, Chevron, Shell, and BP—part of what has been dubbed Big Oil—out of the developing world, seizing their concessions and handing them over to their own national oil companies. In the decades since, however, OPEC has quietly become a friend to Big Oil. OPEC has used its market power to keep prices high, making it profitable for North American and European companies to develop their own oil that was often expensive to produce, such as crudes lifted by deepwater rigs, fracked from shale, or melted from solid bitumen.

From one perspective, the US capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro, and its apparent capture of the oil sector of a founding member of OPEC, looks like a bid to reclaim Washington’s lost influence over the global oil supply. Thus, the Trump administration’s assault on climate action and cleaner substitutes such as electric vehicles and renewable energy may represent a complementary policy to sustain oil demand. While closer alignment between US and Venezuelan production may eventually undercut OPEC’s market power, Trump’s rollback of climate policy may ultimately reinforce global demand for oil in ways that the cartel is well placed to exploit.

Foreign Investors and Energy Nationalists

It is unlikely that the Trump administration’s urging of international oil companies (IOCs) to restart investment in Venezuela will move the needle on supply much in the short term. In the longer term, however, US influence on Venezuelan oil suggests the potential for a larger American role in the global oil market. OPEC has yet to react publicly, although it is certainly paying close attention to any potential challenge to its dominant position.

President Donald Trump has said that he aims to “take back” control of natural resources that US firms lost to Venezuela in past decades. In 1976, the Venezuelan government cancelled the concessions of Exxon, Gulf, Mobil, Texaco, Chevron, and Arco seven years early, albeit with compensation. The 1976 nationalization was the culmination of taxation changes that started in 1958 (by some accounts earlier) and that saw the Venezuelan state tilt the terms ever more deeply in its favor. In further nationalizations between 2005 and 2007, ConocoPhillips and Exxon pulled out rather than acquiesce to the Venezuelan government’s punitive changes in terms. Outstanding claims against Venezuela exceed $10 billion for ConocoPhillips and $1.5 billion for ExxonMobil. Other companies, notably Chevron, accepted the new terms and stayed, which is why Chevron is now in pole position to lead any recovery in Venezuela. These past bouts of energy nationalism are partly behind the reluctance of Exxon and other foreign investors to get back into the country.

Today, Venezuela is considered still one of the riskiest countries for investors.

Today, Venezuela is considered still one of the riskiest countries for investors. In 2021, the most recent year for which the Fraser Institute (a prominent Canadian thinktank) polled mining firms to rank the country’s investment attractiveness, Venezuela came in 76th out of 84 nations. In 1970, it ranked near the top of the list of free economies. With Washington claiming influence over Venezuela—holder of the world’s largest oil reserves—will investment risks decline to reasonable levels?

Credible analysis finds that supply from Venezuela is likely to rise by roughly 500,000 barrels/day over the next year or two, likely through such companies as Chevron, Spain’s Repsol, Italy’s ENI, and France’s Maurel & Prom, which have all applied for US authorization to export oil from the country. For context, that amount is about as much as is produced per day in the North Sea oilfields. Such an increase would push Venezuelan production to around 1.4 million barrels/day, almost as much as Nigeria.

Further gains—beyond the modest bump to 1.4 million b/d—would require wider participation from foreign investors and cooperation from the host government. Trump says that his administration will backstop US investments in Venezuela in some way, but investors remain wary considering the long-term commitments of investing in oil—and the much shorter durations of US presidential terms.

More US-Driven Production?

If Trump’s policy succeeds in coaxing substantial Venezuelan oil to market, it could set the scene for a US-OPEC clash similar to the cartel’s consternation with fracking. Shale was a curveball for OPEC. It took years for the cartel to comprehend the scale of the shale oil increase—the fastest and largest in the history of world oil, and the most price-responsive. As the limits of shale became apparent, OPEC won some breathing space. At prices under $60 or so per barrel, shale can hold steady, but probably will not grow much. The top Tier 1 geology that sustains shale oil production is being depleted, which means higher oil prices will be needed to maintain constant output. Although fracking turned the United States into the world’s largest oil producer, that position could be temporary.

Adding Venezuela to the mix of US-controlled production throws OPEC another unpleasant surprise. Some Venezuelan production is profitable at $25-$30 per barrel. Even if the government’s claims of 300 billion barrels of oil reserves are exaggerated, there is unimaginable room to run. Were the United States and Venezuela somehow to join forces in producing oil—voluntarily for Caracas or not—OPEC’s market power would again come under challenge. This is not a scenario that OPEC can wait out, as it could with shale. OPEC and its OPEC+ allies would still influence a large share of the market, and would still set output quotas among members. But OPEC would not be able to do much about US moves in Venezuela, short of flooding the market in “price war” fashion.

Hurdles to Implementing the Trump Plan in Venezuela

Of course, many improbable pieces must fall into place for all of this to happen. And it would require at least $100 billion in investment over a decade. Among the prerequisites are:

- A major improvement in US-Venezuela relations;

- The lifting of US sanctions on the Venezuelan oil sector; and

- The lifting of Venezuelan legal prohibitions on foreign ownership in the oil sector.

If such developments occurred, US and foreign oil firms would then have to throw caution out the window and make enormous investments amid huge political, regulatory, and institutional risks when there are less risky opportunities elsewhere. Initial signs today point to deep skepticism toward Venezuela in the US oil industry, partly because the oil market is already well supplied. It is hard to imagine all the necessary pieces falling into place during this decade, much less within the remaining three years of Trump’s term.

Making Oil More Competitive with Renewables

For OPEC, another aspect of the Trump administration’s energy policy looks more upbeat. A strategy is taking shape that does not just bolster supply of oil, but also aims to boost oil demand by kneecapping oil’s emerging competitors. The administration is undermining climate action policy and some of its proposed energy solutions—wind and solar power, batteries, and electric vehicles (EVs)—while boosting such other solutions as nuclear and geothermal power. The Trump administration has used nationalist and protectionist rationales for its approach, in light of the Chinese and European prominence in those industries. The overall thrust of Trump’s policy is to make EVs and renewables less competitive in the US market. Automakers have responded by cutting EV production lines and by reprioritizing fuel-burning models.

Cheaper oil can help gasoline-powered cars compete with electric vehicles.

As cheaper oil can help gasoline-powered cars compete with those powered by cheap solar and batteries, there could be a silver lining to the Trump administration’s attempt to rebase oil prices at lower levels. Under a different contractual and tax regime, low-cost Venezuelan production would arguably improve oil’s competitive advantage versus cleantech. Lower oil prices would hurt short-run profits. But cheap oil would also serve to increase oil consumption and perhaps to delay the eventual peaking of oil demand.

For OPEC, Trump’s actions are likely to have long-term positive and negative outcomes. The combined effect could be structural: revitalizing the attractiveness of oil and delaying the eventual peaking of oil demand. Of course, all this comes at the cost of a more deeply damaged climate.

Conclusion: How Might OPEC React?

How might OPEC react to Trump’s Venezuela moves? Venezuela is still an OPEC member but has been sidelined by the falloff in its oil production. It has not been an active player in cartel decision-making since 2001-2003, when successive Venezuelan officials led the organization.

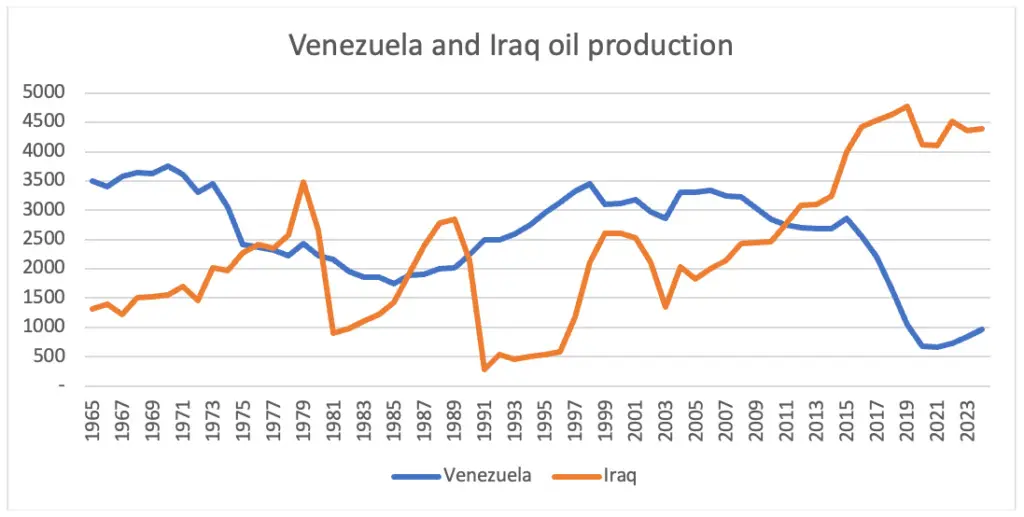

The revival of production by another OPEC founder, Iraq, offers hints as to how a Venezuelan resurgence would be treated. Iraq’s production peaked in the 1970s, hit lows under 1 million barrels per day (b/d) (Figure 1) under US sanctions in the 1990s, and has steadily climbed since the 2003 US invasion. OPEC has only recently begun punishing Iraq for exceeding its quota. OPEC would probably accommodate a Venezuela revival in similar fashion, with the cartel standing aside until Venezuela reaches its previous peak.

Fig. 1: Iraq oil production (orange line) bottomed out in the 1990s, and has climbed since the US invasion in 2003, surpassing its early peak in 2015. Venezuela (blue line) has a long way to go to reach its 1970s peak of 3.7 million barrels per day. Source: author’s compilation from https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review

Perhaps more significant for OPEC is Trump’s positioning of the United States to be able to exert more influence over the oil market by undermining other nations’ sovereignty over their natural resources. The so-called rules-based international order—largely established by the United States through the UN Charter after World War II—provided the legal rationale that enshrined oil as a sovereign national resource, control of which rests with host governments. The need to follow those rules caused American and European companies to lose their grip on global oil by setting in motion states’ expropriation (nationalization) of foreign oil concessions across the developing world. In 1970, western IOCs controlled 85 percent of global oil reserves. By 1980, the total had fallen to 12 percent.

Can Washington and US firms regain dominance in the oil sector by overturning the post-World War II rules? This question is no doubt already generating much discussion in the capitals of OPEC member states.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock/Donne Bryant