While awaiting the perennial renewal of the mandate for the UN monitoring force (MINURSO, or Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara) in Western Sahara at the end of April, there has been some political anxiety in North Africa vis-à-vis the upcoming resolution of the United Nations Security Council. Local politicians and activists wonder about the viability of the UN Secretary-General António Guterres’s new recommendation for resuming “direct negotiations with a new dynamic and a new spirit,” as presented to the Security Council.1 He also proposed a budget of $55.3 million for the maintenance of MINURSO for the period July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018.

This outlook seems to be a déjà vu scenario in the evolution of the UN’s approach, over more than four decades, as it attempted to bridge the gap between the Moroccan government and the Polisario Front. Some critics argue against the Security Council’s “lack of will rather than any paucity of inventive solutions.”2 Now, after four rounds of the Manhasset, NY, negotiations since 2007 (known as Manhasset I, II, III and IV, which were initiated by Security Council resolution 1754), both parties do not seem to be fully invested in the UN’s recurring diplomatic formula, while the potential of holding the referendum has been undermined since 1991. So far, the lack of resolution of the Western Sahara conflict showcases two major problems:

1. A Catch-22 Situation in the United Nations. The advocacy of direct negotiations as a step forward to reach an agreement that would resolve, as Guterres stated, “the dispute over the ultimate status of Western Sahara, including through agreement on the nature and form of the exercise of self-determination,”3 is problematic. International law experts interpret the current impasse as a result of “the singular normative view that it has been a case exclusively within the law and diplomatic requirements of post-colonial self-determination.”4 To be sure, some 40 years earlier, the United Nations identified the “question” of Western Sahara as one of self-determination.5

Samir Bennis, a longtime observer of the UN’s handling of the conflict, points to some irony when the international organization “is aware of the near impossibility of organizing a referendum of self-determination … and keeps calling on Morocco and the Polisario to reach a negotiated solution acceptable to both parties while at the same time, insisting that any solution should provide for the self-determination of the people of the Sahara on the understanding that self-determination should include independence as an option.”6

2. A Half-Step Engagement with the UN Formula. Morocco and the Polisario have sought a hybrid approach in trying to combine the United Nations’ maneuvering, for the sake of being diplomatically correct, with their own respective diplomatic investments in the Americans, the Europeans, and recently the Africans since Morocco has reinforced its economic ties with several African nations. “It had signed almost 1,000 agreements and treaties with various African countries,” while King Mohammed “had made 46 visits to 25 countries on the continent” since 2000.7

Rabat has shifted toward soft economic power as a tool of mobilizing certain African governments like Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Nigeria, as it resumed its membership in the African Union (AU) January 31, 2017, after a 32-year boycott in protest of the admission of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). However, skepticism has surrounded Morocco’s new move despite its resort to pragmatism and soft power practices within the organization. Still yet, it might not see an easier path and indeed face new battles from inside.8

In contrast, Western Saharan nationalists have continued to seek “the right of self-determination afforded to other former European dependencies. They have constructed themselves as the natives, whereas Moroccans are the settlers, a reflection of the same volatile identity dynamic found in other colonial situations.”9 Consequently, the management of the conflict has been indirectly undermined by Morocco’s and the Polisario’s overambitious strategies of trying to benefit, to the maximum, from two parallel diplomatic tracks: one vis-à-vis New York; and another toward US, European, and African capitals all at once. This can be called the “Four-Approach Dilemma.”

In Retrospect

Guterres’s new hope to bring the parties back to the negotiating table raises questions about the utility and promise of international mediation of the long-standing conflict in North Africa. For more than four decades now, the United Nations has sought to formulate an acceptable solution for both parties by striking a balance between the conflict’s two main buzzwords: “sovereignty and self-determination.”10 Any pragmatic assessment of UN diplomacy would highlight the inefficiency of recycling the same conflict management process, as a promising conflict resolution framework, for nearly 50 years of the stalemate. This approach also presupposes Einstein’s deep reflection on the wisdom of “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Back in September 1991, the Security Council decided to establish MINURSO, as envisioned in Resolution 690 (1991), with the aim of organizing the referendum to give the local population the options of independence or integration with Morocco by January 1992.11 There was significant controversy about the number of eligible voters in the would-be referendum. The late King Hassan II accepted the original peace plan that stated the right to vote should be limited to the approximately 74,000 Sahrawis who were listed on the Spanish census of 1974, and insisted on adding up to 120,000 Moroccans to the list.12

Ten years later, then-UN envoy James Baker presented his draft “Framework Agreement on the Status of Western Sahara,” known as the Baker Plan, to the Security Council in June 2001. In it, he “outlined the possibility of Western Sahara becoming an autonomous Moroccan territory, while exercising internal governance through an assembly and elected executive.” However, both parties rejected the proposal and Baker resigned in 2004. The referendum objective has never been fulfilled after nearly 26 years of the existence of MINURSO.13

Some observers believe “the circumstances for a credible and peacefully achieved referendum would never be better than in October 1975. The Visiting Mission issued its report on October 15 … It had recommended that ‘the General Assembly should take steps to enable those population groups to decide their own future in complete freedom and in an atmosphere of peace and security’….”14,15

Now, the underlying factor in Guterres’s call for resuming direct negotiations is that the United Nations has effectively abandoned attempts to organize a referendum for Western Saharan self-determination. By December 2015, Christopher Ross, the personal envoy of Ban Ki-moon, then UN Secretary-General, declared the negotiating process “stalemated.”16

Legal experts highlight the greater shortcoming as the absence of enforceability: “a weakness here as elsewhere in resolving conflicts under the consensual system that is international law. The right of post-colonial self-determination is therefore weak, notably when the responses of states to attempts at secession in sub-state entities, and in cases of the aggression acquisition of a state or territory, are considered.”17 So far, the United Nations’ hands have been tied beyond monitoring the situation on the ground. Any positive outlook is up to “Morocco to accept the independence option or up to Polisario to give away one of its best cards.”18

Last year, the UN’s engagement with the conflict endured a setback when then-Secretary General Ban Ki-moon used the word “occupation,” during a visit to the region, to describe Morocco’s annexation of the Western Sahara in 1975, which sparked a mass protest in Rabat. UN spokesman Stephane Dujarric tried to contain the row, arguing that Ban’s use of the word “was not planned, nor was it deliberate. It was a spontaneous, personal reaction. We regret the misunderstandings and consequences that this personal expression of solicitude provoked.”19 However, Morocco complained Ban lost his “neutrality” and considered his language an “insult to the Moroccan people.”20 It also announced it was ending its $3 million contribution to the mission, and decided to irreversibly expel dozens of the MINURSO staff from the region. Only 25 of them redeployed to Laayoune in mid-July 2016.21

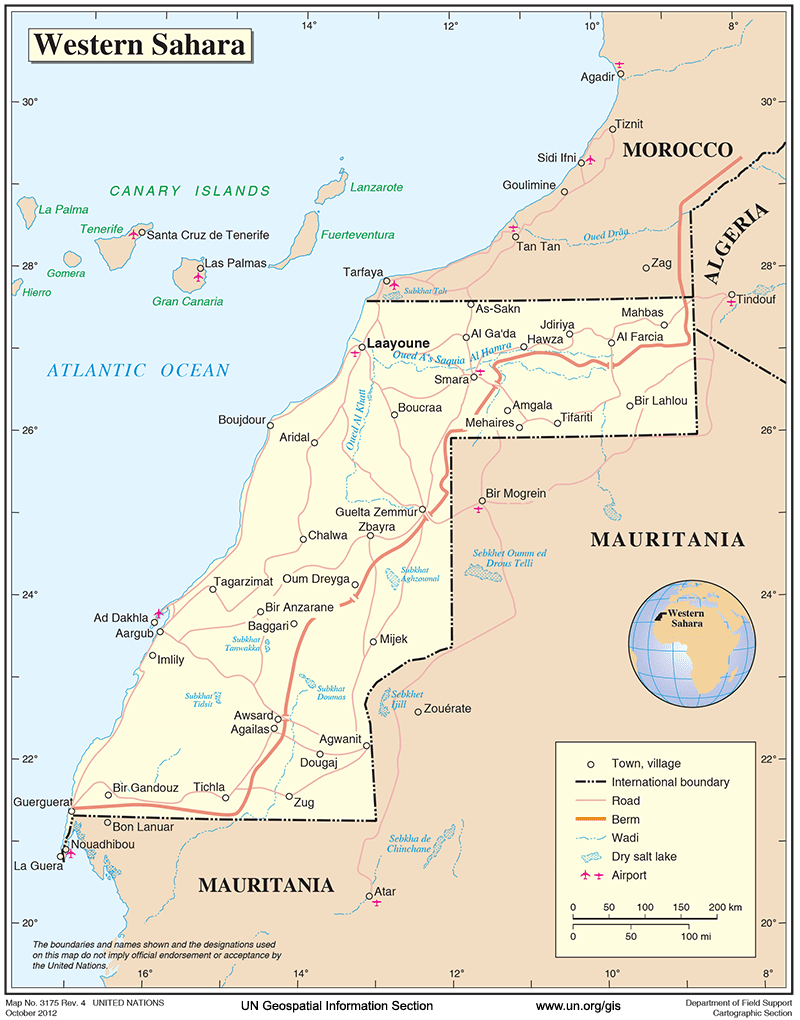

The New Map of Western Sahara (UN, April 2017)

Rival Narratives on Steroids!

The longevity of the most protracted conflict in North Africa has been sustained by two main narratives: “territorial unification” versus “self-determination” with their respective semantic references, and “Moroccan Sahara” versus “Western Sahara.” Some observers have pointed to the complexity of a “metaconflict” that “stems from mutual differences in the self-perceptions that ground Moroccan and Western Saharan nationalism.”22

The new UN report recognizes this split-image of the self-constructed reality of two historical Saharas competing for one land; “the fundamental difficulty is that each party has a different vision and reading of the history and documents that surround this conflict.”23 As a matter of fact, the international community has been idle in addressing the rift between these equally well-construed narratives. As Guterres pointed out, “the parties have significantly divergent interpretations of the Mission’s mandate.”

Morocco views it as “limited to monitoring the ceasefire,” whereas the Polisario perceives the organization of the long-awaited referendum on self-determination as “the central element of MINURSO’s mandate.”24 The Moroccan position remains faithful to the promise of the 1975 Green March to reclaim the Sahara from the Spaniards, and Rabat refers to it as the “Saharan provinces” or the “Southern Provinces.” King Mohammed “stated that the Kingdom would spare no effort to ensure the success of the negotiations within the framework of the Kingdom’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.”25

With the diplomatic assistance of neighboring Algeria, the Polisario’s position has maintained framing the conflict as a clear-cut case of decolonization and thus self- determination. It has leaned on the construct of moral politics and international legality, asserting that the Western Sahara is a non-self-governing territory under foreign occupation and awaiting self-determination.26 New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof once argued that the biggest theft of Arab land is “Morocco’s robbery of the resource-rich Western Sahara from the people who live there.”27 Out of 87 states and international organizations, including the United Nations, the European Union, and the African Union, which support “the right of self-determination of the Sahraoui people,” 41 of them do not recognize the Sahrawi Republic whereas 36 states do.

As a result, the ideological showdown has not waned for more than four decades now. Moroccan nationalism and Western Saharan nationalism have outperformed each other in magnifying their respective existential threats even after the cessation of hostilities in 1991, after a 16-year war. The facts on the ground tend to become more cast in lead over time.28 These factors have perpetuated the deadlock while the parties keep pushing for a zero-sum outcome.

The psychological and cultural residue of self-victimization on both sides, in the name of nationalistic “territorial unification” and nationalistic “self-determination,” has deepened the ownership of the conflict. Furthermore, mutual insults, threats, and injuries to each side’s core values, “constitute a necessary and underlying, albeit ‘imaginary,’ condition that makes this specific conflict possible and thus far irreversible.”29

The war of narratives and contested “legitimacy” and “illegitimacy” remains forceful between the parties and their regional and international backers. Morocco and the Polisario have serviced their claims as an open-ended competition for global recognition. Two distant international linkages can be identified here: 1) the French-American consensus as a shared dedication to “the stability of the Moroccan monarchy that trumps all else, including the interests of peace and international law in Western Sahara”;30 and 2) the Algerian-African consensus since “preexisting tensions between Rabat and Algiers have been exacerbated by Algeria’s support for Polisario.”31

The international linkages are a typical feature of all protracted conflicts in the Middle East since they involve, as conflict theorist Edward Azar asserts, “political-economic relations of economic dependency within the international economic system, and the network of political-military linkages, constituting regional and global patterns of clientage and cross-border interest.”32

While maneuvering the day-to-day ramifications of the conflict, Morocco’s and Polisario’s competitive strategies have consumed a great deal of nationalistic energy, diplomatic resilience, and militaristic financial resources, in addition to fueling distant discourses, fragmenting identities, and colliding worldviews among Sahrawis across the security walls. Consequently, another catch-22 situation has emerged as an asymmetry of powers: Morocco’s military power to control the region versus the Polisario’s diplomatic power to maintain the political and moral pressure on Rabat. Georgetown University Professor Emeritus, Jon Voll, argues that the combination of the Polisario’s inability to have a military victory and Morocco’s inability to have diplomatic victory “emphasizes the old divisions.”33

Along these far-off portrayals of the conflict, Moroccan and Polisario officials are strategizing how to capitalize on the new shifts inside and outside the United Nations. One of these shifts is the anticipated nomination of the former German head of state, Horst Köhler, to become the Secretary-General’s new personal envoy for Western Sahara after the resignation of Christopher Ross on March 5, 2017. Both parties are also contemplating the best possible strategy toward the White House, where Donald Trump advocates the policy of non-involvement in foreign conflicts that do not threaten America’s national security.

In mid-April 2017, King Mohammed spent several days between Cuba and Florida, before it was announced that Morocco had restored diplomatic relations with Cuba—after a 37-year rupture in protest of Havana’s strong support for the Polisario front. It was said that he had wished to meet President Trump during his stay in Florida.

Three Modalities

Three significant challenges should be taken into consideration while trying to predict whether the United Nations will design a different approach toward the 42-year-old conflict.

1. The Guerguerat Status. The long-awaited withdrawal of Polisario fighters from Guerguerat, in the southwestern region of the Western Sahara, as a preventive measure against a possible return to violent clashes, may turn into a new military dilemma in a turbulent neighborhood. Guterres has asked the Security Council “to urge Frente Polisario also to withdraw from the Buffer Strip in Guerguerat fully and unconditionally.”34 Earlier in 2017, the United Nations welcomed the unilateral pullout of the Moroccan security forces from the region.35 This move was also hailed by France, Spain, the United States, and the European Union.

Guerguerat, a small village located 11 kilometers from the border with Mauritania and 5 kilometers from the Atlantic Ocean, was the site of new tensions in July 2016 when Morocco deployed 10 of its gendarmerie officers there with the aim of fighting the thriving drug smuggling in the area. Rabat justified its action by its need to deal with the “danger of insecurity” and stated that the operation was “in coordination with MINURSO.” 36

However, the friction had symbolic significance as the Polisario sent around 34 armed combatants to hinder the building of the road. It complained to the United Nations, in two letters, accusing Morocco of violating the ceasefire agreement.37 The Front also complained about Morocco’s continued practice of affixing stamps on MINURSO staff’s passports in the Western Sahara and requiring UN vehicles to operate with Moroccan license plates. It insisted that “the presence of its armed elements in and near Guerguerat was established in self-defence against Morocco’s attempt to change the status quo by paving the desert track.”38 This direct face-off has raised concerns inside the headquarters of the United Nations as well as the African Union.

2. Mismatch of Political Expectations. The lack of political momentum indicates a divergence of intentions vis-à-vis the upcoming round(s) of negotiations. The laid-back positions of Morocco and the Polisario, after several rounds of direct negotiations since 2007, may not validate the new hopes of UN diplomacy after the Secretary-General expressed his intent “to propose that the negotiating process be re-launched with a new dynamic and a new spirit.” He also highlighted the regional contributions of other stakeholders to support the desired progress, and called on Algeria and Mauritania, as neighboring countries, “to make important contributions to this process.”39

The road to new negotiations is full of growing hurdles. The Polisario “insists on the referendum with independence as an option and says only Morocco and Polisario should be at the negotiating table. A Polisario representative said talks should not abandon progress made by former” envoy Ross. Further, “First, MINURSO should return, and should be able to do its work to prepare the referendum. We hope the new envoy will continue with what Ross started and not start from the beginning again.”40

On the flip side, Moroccans seem to be favoring the new trajectory in New York with cautious optimism, since there is a call for neighboring countries to participate. In a comment to the new UN report, a Moroccan foreign ministry source stated that, “The tone has clearly changed, and the parameters have taken into consideration a realistic approach that demonstrates the will to protect a certain degree of objectivity.”41

3. The Human Rights Card. To add to the complexity of the conflict, Polisario and human rights activists are not at ease with Guterres’s decision not to include human rights monitoring in the Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps in the new mandate in MINURSO this year. In 2015, Ban Ki-moon argued for an “independent and impartial understanding” of the human rights situation in the Western Sahara. “I call on the Parties to continue and further enhance their cooperation with United Nations human rights mechanisms and OHCHR, including by facilitating OHCHR missions to Western Sahara and the refugee camps near Tindouf, with unrestricted access to all relevant stakeholders,” Ban said in the report. 42

In the 2016 report, Ban Ki-moon “alluded to the alleged exploitation of human resources and reiterated his call on all relevant actors to recognize the principle that the interests of the inhabitants of these territories are paramount.”43 In Washington, members of Congress are divided over the real concerns of human rights violations in the region. Rep. Joe Pitts (R-Pennsylvania), co-chair of the House Human Rights Commission, stated that, “For far too long, the native peoples have had their rights of self-determination put on hold, while numerous other internationally recognized human rights have been violated by Morocco’s occupation.”44

International human rights organizations like Amnesty International still argue for the need for a human rights monitoring mechanism in the region to ensure that “abuses committed far from the public eye are brought to the world’s attention, holding those responsible to account, and improving respect for human rights.”45

Distant Diplomatic Tracks

As the United Nations has had some accomplishments and endured several setbacks, it should not bear full responsibility for the multiple-decade deadlock. Nor should the list of stakeholders be reduced to two parties only: Morocco versus the Polisario. The protracted nature of the Western Sahara conflict cannot be fully understood without factoring in the influence of several regional and international governments, at various degrees, within the famous analogy, “too many cooks spoil the broth.”

For example, “Algeria has consistently demonstrated that it will not tolerate a violation of the Sahrawi people’s right to independence as the notion of self-determination had become a cornerstone of their policy and political philosophy since fighting for their own independence against France.”46 Other states like Qadhafi’s Libya, South Africa, Cuba, France, and the United States have played influential roles in the prolongation of the conflict through their support for the positions and actions of both opposing parties.47

The Algerian-African alliance has positioned itself as a strategic counterbalance to the French-American consensus, which has “shared a profound and long standing desire to protect, help, and bolster the Moroccan regime.”48 Paradoxically, as Teresa Whitfield of the International Crisis Group argues, the conflict has been “the unfortunate combination of territorial ambition in Morocco and studied disinterest from states in the broader international community unwilling to jeopardize relations with a strategically located regional power.”49

In short, the current composite diplomatic landscape features a conflict that has progressed in four semi-interconnected spheres of political weight:

1. The use of the UN formula as a return to direct negotiations, by necessity and not by choice, between Morocco and the Polisario after the failure of four rounds of fruitless talks in Manhasset, New York, which urged both parties to “enter direct negotiations and in good faith” with the hope of salvaging the Baker Plan (Plans I and II) with US backing in 2007.

2. The US prospect of a political deal has been on Washington’s radar since the Gerald Ford Administration. This pragmatic option has been consistent throughout the administrations of Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush. As Ohaegbulam writes, “This support was decisive in Morocco’s initial attempt to secure control of the Western Sahara and remained solid in spite of Morocco’s destabilizing and precedent-setting” behavior for African states and the whole world.50

Washington has often expressed its support for Morocco’s “credible” autonomy plan, and the late Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Tom Lantos, urged the Polisario to accept Morocco’s “reasonable and realistic offer” of “far-reaching autonomy for the people of the Western Sahara.” The State Department called the autonomy plan “serious, realistic and credible.”51 Still, the Obama Administration pushed toward a fresh look at the human rights situation in the Western Sahara under the umbrella of MINURSO.

In early 2017, the Polisario had high hopes when John Bolton’s name circulated as a possible nominee for the secretary of state position in the Trump Administration. The former US ambassador to the UN has been one of the most vocal American politicians regarding enforcing a referendum in the Western Sahara.52 Back in February 2017, Polisario Secretary General Brahim Ghali wrote to the White House to extend his sincere congratulations on Trump’s election as president.53

3. There is also growing attachment to a Northern European role besides the Southern European position held by Brussels. This shift was reinforced by the new rift between Morocco and the European Union due to the Court of Justice’s ruling in December 2016 that a four-year-old deal between the EU and Morocco covering trade in agricultural and fishery products, known as the Liberalization Agreement,should be scrapped because it included products from the Western Sahara. Advocate General Melchior Wathelet argued in his legal opinion that the “Western Sahara is not part of Moroccan territory and, therefore, contrary to the findings of the General Court, neither the EU-Morocco Association Agreement, nor the Liberalization Agreement are applicable to it.”54

This legal stance triggered hope for progress in the European position among the Polisario camp. However, during her visit to Algiers, High Representative of EU Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice President of the European Commission, Federica Mogherini, stated that, “Our position like our policy concerning Western Sahara remains a position of strong support to the efforts of the UN General Secretary in order to achieving a political just, lasting and mutually acceptable solution which guarantees self-determination to the Sahrawi people, under the UN Resolutions.”55

The Polisario’s lawyers remain hopeful in their pursuit of presenting the question of Western Sahara before the court of the European Union. With the emerging trade war across the Mediterranean, the European position is increasingly divided between two camps: one camp includes the European Commission, a number of members of parliament, as well as some member states like France, and it favors maintaining Brussels’ partnership with Morocco. The second camp, which consists of other European countries including Nordic member states, has opted to take the Polisario position into consideration.56 In short, Europe may end up with two opposite policies toward the Western Sahara conflict.

4. The fourth and last sphere is the hope for an African solution to be shaped by the new African Union after Morocco resumed its membership, with 39/15 votes. There have been mixed signals about the feasibility of an African settlement for a North African conflict. King Mohammed VI stated that Morocco has “absolutely no intention of causing division, as some would like to insinuate,”57 and the Polisario considered Morocco’s readmission “a chance to work together.” The head of the African Union’s Peace and Security Council, Ismail Sharki of Algeria, stated that both AU members “should start serious direct and unconditional talks based on article 4 of the internal constitution of the organization.”58 Now, the Polisario and Morocco serve on the Union’s Legislative Committee.

UN Chief António Guterres also welcomed the AU’s hope that Morocco’s membership “would facilitate the speedy resolution of the dispute over Western Sahara in a manner consistent with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the UN.”59 However, he expressed some concerns after Rabat “did not permit the observer delegation of the African Union, led by Ambassador Yilma Tadesse (Ethiopia), to return to Laayoune and resume its collaboration with MINURSO.”60

Some observers have expressed some skepticism toward Morocco’s African move. An analyst at the Institute of Security Studies in South Africa, Liels Louw-Vaudran, said that, “Morocco’s re-entry to the AU could simply offer the North African state an air of ‘legitimacy’ in seeking its desired solution in Western Sahara.”61 South Africa hopes that in the coming months, “the AU will not allow the matter of the independence of Western Sahara to be swept under the carpet of political expediency.”62

Conclusion: From Divergence to Convergence of Diplomatic Tracks

Having illustrated the dynamics of the Western Sahara conflict and related strategies among various direct and indirect stakeholders, the prospects of settlement, let alone resolution, remain quite dim. The divergence of four parallel tracks of world diplomacy— UN, US, EU, and AU—has generated more challenges and prevented the emergence of one coherent and promising framework of settlement.

The irony is that each track may be counterproductive to another and vice versa. The international and regional linkages either with Morocco or the Polisario have helped generate radicalized narratives around “sovereignty,” “territorial unification,” and “self-determination.” As one analyst put it, “given the impasse in the Sahara, a reframing of the dispute is timely.”63 It is high time to consider fusing the four tracks together into one framework, one language, and one initiative: “the One-Plan Approach.”

References

1 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation Concerning Western Sahara for the Information of the Members of the Security Council,” S/2017/307, April 10, 2017.

2 Anna Theofilopoulos and Jacob Mundy, “Why the UN Won’t Solve Western Sahara (Until it Becomes a Crisis),” Foreign Policy, August 12, 2010.

3 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

4 Jeffrey J.P. Smith, “State of Self-Determination: The Claim to Sahrawi Statehood,” Yahia H. Zoubir and Daniel Volman, eds. (Rienner Publishers: 2005), 19.

5 United Nations, General Assembly,“Question of Western Sahara,” GA/RES/34/37, November 21, 1979. ”

6 Samir Bennis, “Why the UN Failed in the Sahara, Why a New Approach Is Needed?” Morocco World News, May 21, 2012.

7 Conor Gaffey, “Why Has Morocco Rejoined the African Union After 33 Years?” Newsweek, Feb. 2, 2017.

8 Ali el-Aallaoui, “Can the African Union Pressure Morocco to Accept a Referendum on the Western Sahara?” Open Democracy, February 24, 2017.

9 Stephen Zunes and Jacob Mundy, “Western Sahara,” (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010) p. xxiv.

10 Theofilopoulos and Mundy, “Why the UN Won’t Solve Western Sahara.”

11 United Nations, Security Council, “The Situation Concerning the Western Sahara,” GA/RES/690, April 29, 1991.

12ATLIS, Susan Humphrey, “The Western Sahara Conflict”.

13 Ibid.

14 Smith, “State of Self-Determination,” 19.

15 United Nations, “Report on the Visiting Mission to Spanish Sahara,” United Nations, 1975.

16 Maribeth Hunsinge, “Self-Determination in Western Sahara: A Case of Competing Sovereignties?” Berkeley Journal of International Law, Feb 21, 2017, Maribeth Hunsinge, “Self-Determination in Western Sahara: A Case of Competing Sovereignties?” Berkeley Journal of International Law, Feb 21, 2017.

17 Smith, “State of Self-Determination.”

18 Theofilopoulos and Mundy, “Why the UN Won’t Solve Western Sahara.”

19 “UN Chief Regrets Western Sahara ‘Occupation’ Comment,” Al Jazeera, March 29, 2016.

20 Patrick Markey,“Morocco’s U.N. Expulsion Puts Western Sahara Ceasefire at Risk: Movement,” Reuters, March 22, 2016.

21 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

22 Zunes and Mundy, “Western Sahara,” xxiii.

23 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

24 Ibid.

25 Humphrey, “The Western Sahara Conflict.”

26 Theofilopoulou Mundy, “Why the UN won’t solve Western Sahara.”

27 Nicholas Kristof, “The Two Sides of a Barbed-Wire Fence,” New York Times, June 30, 2010.

28 Smith, “State of Self-Determination,” 19.

29 Zunes and Mundy, “Western Sahara,” p. xxiii.

30 Ibid, p. xxv.

31 Ibid, 30.

32 Oliver Ramsbotham et al., Contemporary Conflict Resolution (Cambridge: Polity, 2008), 87.

33 Mariama Diallo, “UN Calls on Moroccan Authorities to Allow Return of Expelled Staff,” VOA News, March 24, 1017.

34 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

35 “Western Sahara,”The Security Council Report, March 31, 2017.

36 Ezzoubeir Jabrane, “All You Need to Know About the Tension in Guerguerat,” Morocco World News, March 10, 2017.

37 Ibid.

38 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

39 Ibid.

40 Patrick Markey and Samia Errazzouki, “U.N. Chief Calls for Western Sahara Talks, Parties Wary,” Reuters, April 11, 2017.

41 “UN Seeks to Broker New Talks on Western Sahara,”Al Jazeera, April 11, 2017.

42 Louis Charbonneau, “U.N. Wants ‘Understanding’ of Western Sahara Human Rights Situation,” Reuters, April 15, 2015.

43 Samir Bennis,“UN Report: Will Guterres Adopt a New Approach on Western Sahara,”Morocco World News, April 20, 2017.

44 Julian Pecquet, “Western Sahara Controversy Hits Congress,”Al Monitor, March 23, 2016.

45 “UN Peacekeeping Force in Western Sahara Must Urgently Monitor Human Rights,” Amnesty International, April 18, 2017.

46 Humphrey, “The Western Sahara Conflict.”

47 Ibid.

48 Zunes and Mundy, “Western Sahara,” xxiv.

49 Teresa Whitfield, Friends Indeed: The United Nations, Groups of Friends, and the Resolution of Conflict (Washington: USIP, 2007), 165.

50 F. Ugboaja Ohaegbulam, “Western Sahara: Lines in the Sand,” African Studies Review 49, no. 2, September, 2006, 113.

51 Pecquet, “Western Sahara controversy hits Congress,”

52

Habibulah Mohamed Lamin, “Trump Victory Sparks Optimism in Western Sahara,” The New Arab, February 8, 2017.

53 Ibid.

54 Dominic Dudley, “Morocco Suffers Legal Setback As EU Official Declares Western Sahara ‘Not Part Of Morocco’,”Forbes, September 14, 2016.

55 “EU Committed to UN Efforts to Achieve Just, Lasting Solution to Western Sahara Conflict,” Sahara Press Service, April 10, 2017.

56Charlotte Bruneau, “EU deeply divided over Western Sahara policy,” Al-Monitor, March 22, 2017.

57 Gaffey, “Why Has Morocco Rejoined the African Union After 33 Years?”

58 “African Union council calls for direct dialogue between Morocco and Polisario,” Middle East Monitor, March 25, 2017.

59 United Nations, Secretary General, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

60 Ibid.

61 Gaffey, “Why Has Morocco Rejoined the African Union After 33 Years?”

62 Samir Bennis, “Moroccan pragmatism: A new chapter for Western Sahara,” Aljazeera, February 13, 2017

63 Smith, “State of Self-Determination.”