With the aid of tribal militias, forces loyal to renegade Libyan General Khalifa Haftar recently recaptured Libya’s “Oil Crescent.” Following that victory, Haftar ominously announced on June 25 that administration of the oil facilities would be transferred to the “transitional” government he dominates in the eastern city of Bayda, instead of the National Oil Corporation (NOC) under the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), based in Tripoli. That announcement was tantamount to an institutionalization of an east-west division of the country following the establishment of a parallel central bank in the east. But on July 11, the Tripoli-based NOC declared that the general had agreed to cede control of the oil installations under his sway to the GNA, thus—at least temporarily—blunting talk of a dangerous partition.

Shifting Control of Libya’s Oil Crescent

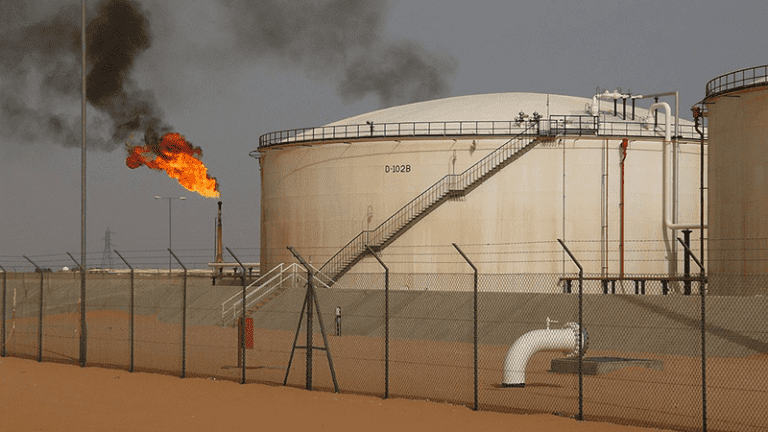

The Libyan Oil Crescent fans out across the country’s coastline, starting at the port city of Zuweitina through to the towns of Brega, Ras Lanuf, and Sidra. The road from Sidra leads to the city of Sirte and the Libyan interior. Installations within this region include oil storage tanks and ports as well as refineries and intermediate manufacturing plants for petrochemicals. The oil fields that feed these installations lie in Sreer, Nafoura, Masala, Bayda, and Majed, with some between 300 and 500 kilometers to the south of Benghazi. Overall, the Oil Crescent is viewed as the backbone of Libya’s hydrocarbon resources, making it the most significant region in the country.

Following the February 2011 uprising, Libya’s Oil Crescent was caught in a tug-of-war between loyalists of former strongman Muammar Qadhafi and armed revolutionary battalions. By 2012 and through the first half of 2013, relative improvements in the region’s stability had allowed the export of crude oil to resume to pre-revolution levels. By July 2013 however, an armed group calling itself the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), under the leadership of Ibrahim al-Jadran of the Magharbeh tribe, took hold of vital installations in the Oil Crescent and quickly put an end to oil exports for more than two years. In doing so, the PFG was given political backing and propaganda support by the same constellation of groups that would come out in support of the Karama Operation launched later by General Haftar. A December 2014 attempt to recapture these installations by force, led by a coalition calling itself “Libya Dawn,” was ultimately unsuccessful.

Oil accounts for the main—if not the only—source of income in the country.

By January 2016, an armed group loyal to the so-called Islamic State (IS) and previously based in Sirte launched an attack on the installations in the Oil Crescent, targeting the port cities of Ras Lanuf and Sidra. While members of the PFG were killed or wounded and some of the infrastructure damaged, the group could not maintain its gains for long and was forced to withdraw rapidly. By September, Haftar loyalists had launched a counter-attack and, through a series of understandings with tribal leaders of the Magharbeh, managed to secure all of the installations of the Oil Crescent with minimal fighting. By March 2017, the Benghazi Defense Brigades were able to retake, in a short time, the locations that Haftar’s forces had captured and to hand these over to the Government of National Accord. It took Haftar loyalists only two weeks to launch a counter-offensive and retake all they had lost. At around this time, the PFG seemed to disappear before its leader resurfaced in mid-June 2018. In a statement, PFG leader Jadran announced that his forces were seeking to reclaim the Oil Crescent installations from Haftar loyalists.

The Role of Regional Players

Jadran’s faction was able to take the two ports of Sidra and Ras Lanuf in a few hours. They succeeded in capturing scores of Haftar loyalists as prisoners alongside a number of foreigners who, the PFG claims, were members of the Sudanese Justice and Equality movement. PFG control of the sites only lasted a week before Haftar loyalists were able to reclaim the Oil Crescent.

Important for Haftar is the backing he receives from the United Arab Emirates and Egypt. UAE aircraft have long provided air support to his forces; in fact, the UAE’s involvement has become an open secret. Egypt also is most interested in Haftar’s continued control of the oil installations in Libya and has assisted him militarily. In the middle of the disarray and intrigue that have surrounded the export of Libyan oil since 2013, it seems that Egypt might stand to gain from keeping Libyan oil installations in Haftar’s hands. The Oil Crescent, and the region surrounding it, are vital to Egyptian interests, giving the regime of Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi more reason to jealously protect Haftar’s control of the territory. To further these aims, the Egyptian government has made symbolic overtures to the tribal chieftains who are dominant in the Oil Crescent.

The Specter of a Divided Libya

Haftar’s original announcement that the oil installations under his control would be handed over to an alternate, parallel structure outside the control of the GNA was another reminder of the dreaded possibility of partitioning the country. Indeed, his Karama Operation of May 2014 threatened to do that since he signaled clearly his desire to strike out on his own and independently of the Tripoli government. Further examples of the institutional fissures in the country, which have military, political, and even social repercussions, include the move of the country’s legislature (House of Representatives, HoR) to Tobruk in the east as well as the establishment of a parallel “central bank” in Libya answerable to the pro-Haftar cabinet, led by Abdullah al-Thinni in Bayda. Haftar has even sought to institutionalize the division of Libya’s military, announcing the establishment of the “Libyan Arab Armed Forces”; these are composed of armed factions and tribal fighters, all loyal to him and based in the eastern Barqa region and in the western areas surrounding Zantan and the Warshefana districts around the capital, Tripoli. Haftar serves as the commander-in-chief and has received the backing of a number of tribal legislators under the leadership of the president of the Tobruk-based HoR, Aqilah Saleh.

Egypt and the United Arab Emirates are assisting General Khalifa Haftar in the east of the country where he has a separate institutional structure challenging Tripoli’s Government of National Accord.

Had Haftar gone through with his June 25 announcement to maintain control over the oil installations and revenue, Libya would have been subjected to serious and chilling repercussions. To begin with, oil accounts for the main—if not the only—source of income in the country; unavoidably, therefore, any attempt to monopolize a sizeable portion of the country’s oil would lead to huge and multifarious internal struggles. Furthermore, controlling revenue could make partition easy. It was notable that some important proponents of federalism for post-conflict Libya quickly embraced Haftar’s move to appropriate the oil infrastructure and revenue. Although “federalism” does not in itself entail partitioning the country, it is difficult to avoid that association today, given the strong centrifugal forces at play and the hurdles hindering reconciliation between the different political factions.

Indeed, the geography and size of the Oil Crescent are sources of contention among political groupings with diverging views on the future internal structure of Libya. The crescent extends west to reach Sidra and Bin Jawad, two cities outside the eastern Barqa region but under Haftar’s control. This extension has caused friction between those calling for federalism and those advocating a unitary state. Based on the administrative divisions set out in Libya’s 1951 constitution, the city of Ajdabiya is the westernmost edge of the eastern districts, which leaves most of the Oil Crescent installations outside the Barqa region. This has prompted the federalists to demand that a new administrative boundary be drawn at Wadi al-Ahmar next to Sidra and Bin Jawad, which would place all the Oil Crescent’s installations within the administrative boundaries of the Haftar-controlled east. This is a major point of contention that will likely only be resolved through serious negotiations that would lead to a new constitutional framework for the state.

Regional and Global Imbalances

There does not appear to be a definite, clear, and coherent international stance toward the ongoing conflict in Libya. While Egypt directly backs Haftar and the tribal communities that support him, Tunisia is attempting to walk the tightrope of neutrality. Algeria continues to be circumspect in its approach to the conflict on its eastern border but is also working to limit Egyptian and Emirati influence in western Libya. Western powers are similarly divided and diverse in their approach despite the spectacle of regular pronouncements of concern and joint effort: while France has provided support—sometimes openly—to Haftar, Italy tries to ensure that it has equally good relations with all the parties to the internal conflict in Libya. For their parts, the United States and Britain are increasingly trying to extricate themselves from the minutiae of Libyan affairs.

Controlling oil revenue independently of the internationally recognized GNA could make Libya’s partition easy. This is why calls for a federal system are dangerous.

It is possible that dominance over a natural resource that is so vital to the Libyan economy will have repercussions for the country’s economic partners abroad. Libya’s OPEC production quota of roughly 1 million bpd is fairly modest. An increase in oil prices will boost Libya’s revenues now that Haftar has agreed to cede the oil installations to the GNA. At any rate, the general may not have had much luck marketing his crude had he kept the oil infrastructure under his control since the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy all demanded that Libyan oil not be exported through the backdoor. The United Nations has also joined this chorus, demanding that Libyan oil fields be returned to the recognized NOC.

The Italian military has even gone so far as to flex its muscle to safeguard the oil wells operated by the ENI company, an Italian multinational, and protect the workers there. While avoiding an explicit mention of Haftar, Italy’s Minister of Defense Elisabetta Trenta couched her remarks about protecting oil revenues in the language of counterterrorism action. Aside from their concern about this economic situation, however, the same western states that worked with all of Libya’s factions to accept a Government of National Accord as a power-sharing arrangement have done little to nothing to rein in the Haftar loyalists, who are working hard to undermine Libyan institutions.

Conclusion

Haftar’s original move to hand over control of installations in the Oil Crescent to an institution answerable to him would have only served to further complicate Libyan politics and to entrench the rampant fragmentation of Libyan institutions. But his change of mind indicates that he may be listening to alternative advice, specifically that of his European friends and the United Nations—advice that urges an approach to avert further fragmentation of the Libyan state and nation. In light of the fact that certain important international players are avoiding direct involvement in Libya, it is incumbent upon Libyans themselves to determine how best to end the chaos in their country and prevent its partition.

This article was first published on July 10, 2018 by Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Doha, Qatar. It has been translated from Arabic and modified to reflect the latest developments.