Israel today is witnessing an unprecedented internal struggle that has split Israeli society into two contentious groups separated by what is, at least at the present time, an unbridgeable gap. These two groups are organized into two conflicting camps. The first is the neo-rightist camp that currently controls the government and that comprises different strands, including populists, Kahanists, nationalist and religious ultraconservative Zionists, and Haredim who have undergone continual nationalist Judaization. The second camp is the opposition that is currently protesting against Israeli Minister of Justice Yariv Levin’s plan for a judicial coup, which includes parties from the center, the left, and the statist right. Each of these two camps has its own class, social, and ethnic attributes, as well as its own vision of the nature of the state. Both, however, agree on the Jewish nature of the state of Israel and on Zionism.

The right considers the opposition to have failed in realizing “true Zionism,” despite having monopolized governance by employing the elite. Meanwhile, the opposition views the right as destroying Zionism and taking the state that it once built to the brink of the abyss by transforming it from a democratic Jewish state into a dictatorship. The new extreme right is moving in the direction of rebuilding the Zionist project on new foundations that replace soft Israeli secular Zionism with another type of Zionism, one that emphasizes Jewish nationalism, the values of conservatism, Jewish supremacy, exclusive rights for Jews between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, and achieving full Jewish sovereignty over the “Land of Israel” (Eretz Yisrael).

This article seeks to study the current situation by linking it with the relationship the two groups have with the Zionist colonialist project and the struggle over symbolic colonialist capital. Accordingly, the paper will study the current dispute as a multi-class disagreement—with social, historical, and psychological dimensions—between the founding colonialists and the new colonialists in Israel.

The Founding Colonialists

In a publication titled, “The End of Ashkenazi Hegemony,” Israeli sociologist Baruch Kimmerling identified Israel’s Ashkenazi Jews, secularists, old time socialists and nationalists, and all those who endorsed their ideology as the builders of the Zionist project, the authors of its principles, and the leaders of the colonialist enterprise in Palestine up until the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel, which this same group then led in its first decades of existence. These founding colonialists led the process of ethnic cleansing and the organized destruction of the Palestinian presence in 1948, and constructed the infrastructure of the Jewish state on the principles of the expulsion of Palestinians and the prevention of their return. They also instituted the state’s secular system, led the process of gathering Jewish immigrants from Arab and Muslim countries and from post-WWII Europe, and sponsored “melting pot” policies that sought to integrate the new immigrants within an Israeli identity that conformed with their western modernist and secularist vision. Furthermore, they established an institutional edifice on a statist principle that separates factionalism from the institutions of the state. According to Kimmerling, the structure of the traditional Ashkenazi Israeli authority thus rested on a combination of economic, cultural, and military hegemony.

Because of its historical role, this group enjoyed the economic, social, and symbolic capital of the Zionist project and formed the economic, cultural, political, and military elite. However, it gradually began to lose its hegemony over its project because of demographic and cultural factors that impacted Zionist ideology, integration policies, and the Jewish state’s democratic edifice, and that led to the emergence of new pressure groups and competing political elites. These factors also helped the emergence of new coalitions capable of contesting the capital controlled by the hegemonic group.

The New Colonialists

The newcomers to the Zionist project were mainly Mizrahi Jews (Jews from Arab countries) who were less affluent and more conservative than Israel’s Ashkenazi elite, and who are usually unable to escape their social heritage. Other newer arrivals included groups of Haredim (ultraorthodox Jews) and religious Zionists. These have constituted the bedrock of the current extreme right and the core of its political and governing elite. What characterizes these groups is the fact that they either joined the Zionist project relatively late, after the establishment of Israel, or were on its margin historically. They were also appendages to the secularist Ashkenazi elites who were led by the Mapai Party (Workers’ Party of the Land of Israel) in the early years of the state. This is why these groups do not enjoy the symbolic capital that the founders who led, executed, and wrote the original precepts of Zionism had.

Using social changes and political alliances allowed the newcomers to build and consolidate political capital, but without being able to simultaneously accumulate symbolic, economic, and cultural capital, which remained the purview of the founding elites and was reflected in the nationalist narrative and in the country’s cultural, judicial, and economic structure. This dichotomy created a chasm between the newcomers’ political capital on the one hand and their overall weak cultural, economic, and symbolic capital on the other, which resulted from the skewed power relations that the Zionist project created.

Mizrahi Jews joined Zionism after the establishment of Israel and did not play an important role in creating Zionism.

Mizrahi Jews joined Zionism after the establishment of Israel and did not play an important role in creating Zionism and its ethos and vision, or even in realizing the Zionist project through the use of force prior to 1948. But Israel’s policies of integration, the building of the political parties, and the structure of the army and the opportunities it provided without the need for specialized certification all contributed to the elevation of political and military elites, even to the ranks of chief of the general staff, president of the republic, and important ministries. This, however, was not accompanied by a parallel elevation of judicial, intellectual, and cultural elites because of the structural impediments ingrained in the educational system and its relegating the Mizrahim geographically to the periphery and, consequently, to the poorer classes.

The Haredim, on the other hand, had historically opposed Zionism and continued to object to the establishment of a Jewish state in 1948 until they signed the Status Quo Agreement with the first prime minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, which gave them a form of autonomy within the state. They, too, were able to translate their electoral power into tools to create new political elites. But because of the structure of their communities, their focus on studying the Torah, and their ultraconservatism, they failed to elevate cultural or economic elites and thus became one of the least fortunate groups in Israel’s current economic structure.

Religious Zionism was only a marginal sectoral trend in Zionism and its adherents chose to support the rule of Mapai before becoming the vanguard of the settler project after occupation in 1967. The Mizrahim’s joining the Zionist project after the establishment of the state caused a demographic shift in the founders’ social structure. Ashkenazi Jews constituted 85 percent of Jewish society in Israel in 1948; but after that, they dropped to 50 percent, the other half being Mizrahi Jews. With the demographic growth of Israel’s Haredim and the increase in the number of religious nationalists, the numerical power of the country’s secularists gradually decreased, and they were thus transformed from a dominant political majority to about 40 or 45 percent of Israeli society today. This was accompanied by a gradual and serious change among the Haredim from groups “outside” Zionism working in a nonpartisan and sector-based fashion to become an effective actor in politics. This, in turn, was accompanied by a “nationalizing” process and a shift toward the right that eventually drove them into the camp of the neo-right and installed them as one of its central pillars.

As for religious Zionism, it underwent an internal revolution that carried it away from Mapai to become the driving force behind settler Zionism. The Likud Party, which was built out of a merger of multiple parties, including Herut and a modest Ashkenazi party outside of the Mapai establishment, succeeded in winning the elections of 1977 after building an alliance with the “new Zionists.” Today, this party leads the extremist neo-right, but it, too, underwent deep changes, moving from a right-wing liberal party to a populist rightist party that revolves around the personality of a charismatic leader.

The Current Dispute in Context

It is possible to understand the current dispute as a multilayered one that is taking place in a dynamic colonialist environment in which the newer colonialists are challenging the founders in order to replace them and assume their historical position by building a strong activist hegemony that restores what they call the “real meaning of Zionism.” This is why the leaders of the extreme right do not criticize the original Zionism but rather admonish those who “drifted away from it” and claim that they alone represent “true Zionism.”

Thus, in the current social scene, which is built on agreement between the right and the opposition on the principles of Zionism and the Jewishness of the state, and with the teetering of Ashkenazi secularist Zionism and the emergence of religious, Haredi, settler, conservative Mizrahi groups, exaggeration in rhetoric and practice has become an inseparable part of the struggle over authority and hegemony. Standing in opposition to the secularism and statism of the founders is a new extreme right that is agitating for radicalism in a more explicitly Jewish state, for a Jewishness that is more nationalist, for a nationalism that is more Jewish, and for settling the score with what they call the “Palestinian enemy” and establishing full sovereignty and control over the land of Israel.

Founder Zionism was transformed from a violent colonialist behavior prior to 1948 to a statist colonialist one that emphasizes institutionalism, judicial bureaucratization, and liberal democracy. In contrast, the new Zionism is a mixture of activist settlers, religious pioneers, and nationalist ultraconservatives who are represented by the “hilltop youth,” who now lead the effort to colonize the West Bank and who commit acts of violence against Palestinians. The statist colonialists use the state’s institutional and legal tools to realize their project, thus benefiting from the power of the state and its protection and colonialist heritage, and from their Jewish messianic enthusiasm for settlement, which they see as an integral part of realizing Zionism.

Standing in opposition to the secularism and statism of the founders is a new extreme right that is agitating for radicalism in a more explicitly Jewish state.

As regards the Palestinians, this behavior takes the form of marauding Israeli extremist groups, as happened in the burning of the town of Huwwara or during the “Dignity Intifada” in 2021. The rightist government has resorted to quickly demolishing the homes of Palestinians conducting operations even before an investigation is conducted, and undertaking oppressive measures against prisoners, just to show its ability to punish. With the continuation of the struggle, “exaggerating” the response is the new colonialists’ tool to use against the founding colonialists, which preserves their place in the larger nationalist discourse and collective myths, not as marginal adherents but as active practitioners.

In this context, the occupation of Palestinian lands in 1967 gave the new Zionists an opportunity to play a desired role in the colonialist nationalist project that they missed out on in 1948. It also gave them an opportunity to become new pioneers of settlement to finally achieve the “interrupted” Zionist project.

The colonialist level is realized by confronting the Palestinians and crushing them, since defeating the native Palestinians and controlling the land is the rite that canonizes the new Zionists in the general colonialist nationalist project as “the lords and owners of the place.” But this project remains unfulfilled, for such canonization has not been accompanied by the killing of a symbolic father, to use Freudian terms, a killing that would allow the newcomers to truly inherit the founders’ position. In other words, the new Zionists have almost succeeded in becoming founder Zionists, either through a “judicial revolution” that allows them to destroy the last of founding Zionism’s bastions, or by stripping them of their legitimacy, blockading them, and preventing their return to power following structural changes in the system, or by canonizing themselves.

Indeed, the new Zionism, under the leadership of the new right, steals founder Zionism’s central values and recycles them to fully accomplish the Zionist project after the founders failed in its mission: achieving full sovereignty over the land of Israel through settlement (in all its forms and with all its tools), constant Judaization and the solidification of Jewish supremacy between the river and the sea, vanquishing the Palestinians, and re-Judaizing the “first Zionists” whose Jewishness and identity have, in the new Zionists’ view, been weakened.

This paper was first published in Arabic by Madar: The Palestinian Forum For Israeli Studies on March 27, 2023.

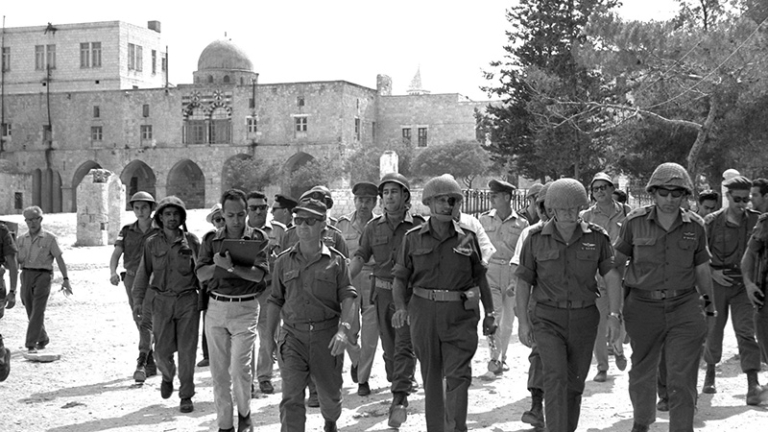

Featured image credit: GPO