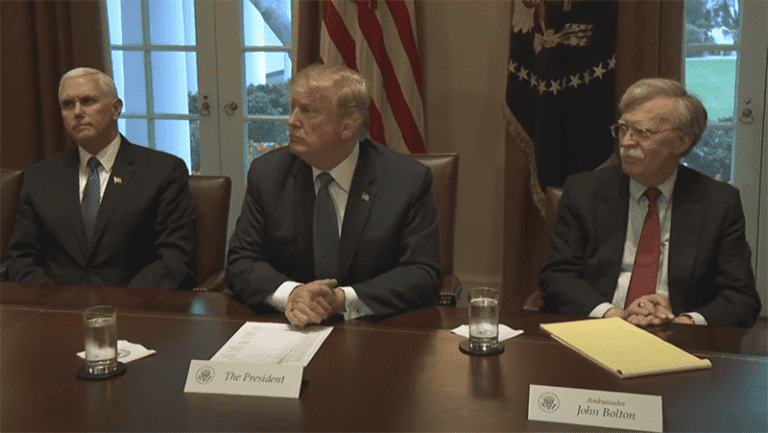

Many experts and media pundits inside and outside the Washington, DC beltway argue that the appointment of John Bolton as national security advisor will not only drive the final nail into the coffin of the Iran nuclear deal, it will also open the door to a US military attack on Iran. This prediction makes sense. A former US ambassador to the United Nations under George W. Bush, ultra-hard-line strategist, and Fox News commentator, Bolton seems to operate with the motto “bomb first, ask questions later.” During testimony in which this author participated before a subcommittee of the US House of Representatives in July 2013, Bolton’s bombast was evident when he advocated for an Israeli attack on Iran. For him, the purpose of using force is not merely to damage or destroy Iran’s nuclear program but to topple its rulers, too. Regime change—which he insists is the “only long term solution”—has always been Bolton’s ultimate goal.

Bolton’s approach will surely be endorsed by the new nominee for secretary of state, outgoing CIA Director Mike Pompeo. As a devoted Christian evangelist who was previously a Tea Party Republican congressman from Kansas, Pompeo has a zealous hostility toward Iran, one that might exceed that of Bolton. He will likely back Bolton if and when he makes the case for war; what is more, Pompeo will take steps to ensure that the State Department does not get in the way. Indeed, if the recent “scrubbing” of Rex Tillerson’s name from the State Department web site (together with all his speeches and press statements) is any indication, the White House intends to blot out the short-lived legacy of relative moderation that Tillerson represented.

Trump has inherited a nuclear deal whose core terms John Bolton and Mike Pompeo utterly reject.

Still, there are other factors and circumstances that might incline Trump not to pursue war with Iran—at least for some time. To begin with, it is far from clear that he is ready to suffer the political and economic risks that could come from a direct military confrontation with the Islamic Republic. With the US military focusing on destroying the remnants of the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Syria and struggling to defeat the Taliban in Afghanistan, Secretary of Defense James Mattis is likely to make the case against using force. This is the good news. The bad news, however, is that with the ascendancy of the super-hawks, Trump will very likely abandon the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the Iran nuclear deal—and quickly reimpose sanctions on Iran.

Doing so will surely not rebound to the favor of the United States. On the contrary, Iran could reap substantial diplomatic and economic benefits, particularly if China, Russia, and especially the European Union countries decide to go their own way regarding Iran by expanding economic relations, trade, and engagement with Tehran. This would leave the administration isolated in the global arena, save for the support it would continue to enjoy from the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Israel. Under these circumstances, the pressure on Trump to take some kind of military action will increase. Ultimately, Washington could be the big loser, whether it limits its actions to walking away from the JCPOA—which is no small matter—or worse, chooses to pursue a military confrontation with Iran.

The Push and Pull of the Super-Hawks

Indeed, despite its many risks, the prospects for war are very real. They are nourished by Trump’s deep hostility toward the Islamic Republic of Iran and his adamant opposition to the JCPOA. Trump made his position clear during the 2016 presidential campaign, when he not only declared the agreement a “disaster” and the “worst deal ever negotiated,” but also stated that if elected his top priority would be to dismantle the agreement. Today, however, Trump’s problem is that he has inherited a nuclear agreement that is based on a deal whose core terms Bolton and Pompeo utterly reject; and it is one that cannot be spurned without leaving the United States isolated and largely on its own.

The JCPOA requires that Iran roll back most of its nuclear program but allows it to retain limited uranium enrichment under a strict regime of international supervision and inspections. In return, the international community has pledged to reduce and eventually eliminate all nuclear-related economic sanctions. But American super-hawks have long advocated “zero enrichment” and reject negotiating the sanctions away. For Bolton, sanctions are not a bargaining asset; rather, they are key strategic tools in a wider strategy to topple the Iranian government. The fact that the international community blessed an agreement that, at its core, negates the super-hawks’ basic positions presents Trump with a bad headache: if he accedes to the hawks and walks away from the nuclear deal, the United States could provoke a backlash from Western European states. Indeed, France, Holland, Germany, and other European countries would feel entirely justified in expanding the trade and investment opportunities they have received—or anticipate reaping—from the removal of nuclear-related sanctions. This would thus leave the United States internationally isolated and struggling to support a greatly weakened sanctions regime.

Seeking to avoid this dire outcome, in October 2017, then National Security Advisor Lt. General H.R. McMaster and Secretary of Defense James Mattis tried to persuade Trump not to renounce the JCPOA. Mattis had already openly broken with the president by declaring before the Senate Armed Services Committee that the JCPOA remained in the US interest; this underscored the Pentagon’s deep concerns about the strategic implications of walking away from the deal. The entreaties of Mattis and McMaster eventually got Trump to agree to steps that fell short of explicitly repudiating the JCPOA. In his October 13 televised statement, Trump announced that based on the authority given to him by the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, his administration “cannot and will not” certify that Iran had undertaken the required measures to merit continued suspension of sanctions. Moreover, he directed the administration “to work closely with Congress and our allies to address many serious flaws,” and on that basis to seek revision of the JCPOA—all of which, Trump claimed, would strengthen a greatly flawed agreement.

Any attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities would provide no guarantee of sufficient damage to dissuade Iran from rebuilding its nuclear program.

This proposal was a nonstarter, as Iran soon made clear. Seeking to salvage the situation, in February the United States began talks with the EU states. The goal was not to revisit the JCPOA, but rather to forge a common framework for “add-on” agreements that might address outstanding issues of mutual concern to the United States and its European allies, such as Iran’s intercontinental ballistic missile program and the sunset clauses in the original nuclear agreement. Whether the Trump Administration believed that such talks could succeed is not apparent, but it was clear that the US-European talks provided some breathing space not merely for the Europeans, but also for US political leaders. Indeed, in a sign of congressional concerns about what would result from any US repudiation of the JCPOA, in early March Senate Foreign Relations Chairman Bob Corker stated that his committee would support any effort by the administration to reach an agreement with EU countries about a framework for addressing US concerns about the JCPOA.

All this is now water under the proverbial bridge. With Bolton and Pompeo poised to remove the life support system that has sustained a barely breathing nuclear agreement, the Europeans will have ample incentive to break with Washington and go it alone. The nightmare of a fragmented international coalition looms on the horizon.

The Danger of Losing the Europeans

Do the Europeans have the economic resources and political will to go down this path? It certainly seems so. As outlined in “The Coming Clash, Why Iran Will Divide Europe from the United States,” a European Council on Foreign Relations report published in October 2017, stated that the Europeans anticipate forging a “vigorous contingency plan to counter US backtracking on the deal.” The plan, the report states, should center on “mechanisms that ringfence European companies from the enforcement of secondary US sanctions.”

Whether creating this kind of “ringfence” is feasible remains to be seen. Some experts, such as Columbia University’s Richard Nephew, argue that the secondary effects of banking sanctions will be substantial. But Nephew further notes that the EU states do have options for mitigating the effects of sanctions and may very well pursue them. Worried or even enraged by Trump’s actions, it is very likely that China, Russia, and the European Union will abandon the United States, an outcome that would represent, as Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has noted (with some satisfaction) “a huge failure” for Washington. Frustrated by Europe’s refusal to support his administration—and also pushed by the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Egypt to confront Iran—Trump might eventually choose to use force. The slide into war could begin precisely when the safety net of diplomacy is torn in half. And once a war starts, it is very likely that Iran would declare that it is no longer bound by the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and thus free to again pursue its nuclear program.

Warnings Against Military Action

Still, there are other factors that might deter the White House from using force, namely three essential reasons. First, experts agree that a limited, short-term attack is not possible: if the use of force were meant to destroy Iran’s nuclear program, it would require multiple bombing raids over weeks and engage the United States in a prolonged war. Second, any attack would provide no guarantee of sufficient damage to dissuade Iran from rebuilding its nuclear program; indeed, Iran might then be expected to follow a concerted effort to pursue a nuclear weapons capacity it has so far been denied. Third, an attack would almost certainly provoke massive retaliation from Iran’s allies throughout the Middle East.

The grim reality is that the United States faces unprecedented security and strategic challenges in Syria and in the wider region. A US attack on Iran is sure to invite retaliatory acts on multiple fronts, opening the door to war between Hezbollah and Israel, not to mention strikes against US forces that could play into the hands of the Islamic State’s remaining forces and allies. Indeed, while Iranian leaders argue that their participation in defeating IS should give Iran a major role in forging any post-IS security policy in the region, if faced with a choice between sustaining the fight against the organization and confronting Washington, Tehran will choose the latter. The UAE and Saudi Arabia might welcome this development, as it would confirm their most dire perception of the Iranian threat. Feeling empowered, both countries would probably escalate their attacks on the Houthis in Yemen, thus provoking further intensification of this already disastrous conflict. In short, the case against war is now more compelling than ever: if war ensues, the Middle East would spin out of control, with unforeseen and possibly disastrous consequences.

The White House’s Iran policy is more likely to advance Tehran’s security and political interests and strengthen Iranian hard-liners.

Paradoxically, it is this very prospect of geostrategic and security mayhem that might keep the Trump Administration from attacking Iran. The most influential advocate for avoiding war is probably Defense Secretary Mattis. The last pragmatist standing among the White House’s top security advisors, he brings the substantial authority of a US military that is probably wary of opening yet another battle front. Judging by past experience and numerous press reports, it is very likely that President Trump would listen closely to Mattis even if the two disagreed with each other.

There is no guarantee that either Bolton or Pompeo will feel constrained by their previous bellicose statements on Iran. Indeed, Bolton has already stated that he will not be tethered to his past pronouncements or writings. As for Pompeo, while his conservative religious background and alleged Islamophobic leanings might incline him to take an aggressive approach to Iran, without troops (or for that matter, the authority of the CIA) to back him up, Pompeo will probably take a cue from Bolton by making loyalty to the president his number one priority.

Loyalty to a president who seems to lack any coherent strategic vision for US foreign policy—and who has evinced a troubling level of emotional volatility—will hardly reassure those who worry about the course of US Middle East policy. But if a strong element of irrationalism shapes Trump’s approach to the region, and to the wider global arena, some basic rational calculations might deter the president from pursuing a war with Iran. These include his concern for avoiding further Middle East military entanglements, all of which would incur a huge human and financial cost. A protracted battle with Iran could produce a massive increase in oil prices and thus trigger a recession within the United States and the West. Trump’s recent call for the United States to “get out of Syria…very soon” suggests that he is looking to disengage from the region’s conflicts rather than to initiate a new battle front. This calculation is unlikely to change even if the president decides to attack Syrian military positions to punish Assad for the recent gas attack outside Damascus. Trump will try to avoid escalation and will certainly oppose the use of any more ground troops in Syria.

This is certainly good news for Iran. As it now stands, the White House’s Iran policy is more likely to advance Tehran’s security and political interests than those of Washington. Apart from isolating the United States, repudiating the nuclear agreement would reinforce the domestic leverage of Iranian hard-liners, who would surely seek to silence any and all voices favoring engagement abroad and political détente at home. And if necessary, they will absorb the blows from a US military attack, to which they can respond on many fronts. Trump’s approach to Iran is thus like music to their ears. For powerful groups such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Trump represents an opportunity, not an obstacle.

In light of these prospects and realities, one can only hope that those remaining voices of pragmatism in the Trump Administration—particularly in the Department of Defense—will find a way to convince the president of the folly that would surely ensue from repudiating the JCPOA. Even more so, they must communicate to him the enormous costs that the United States would pay if and when the president chooses war over diplomacy.