Abstract

Qatari foreign policy presents a challenge for students of international relations. Whereas major theories within the field tend to privilege structural factors in explaining the action of states, and particularly small states, in the case of Qatar, the quality of leadership and the strategies that leadership employs to navigate through the structural constraints—primarily geography—are equally important. One of the main findings of this paper is that the strategies adopted by the Qatari elite since 1995 did alleviate many of the structural constraints which the country would otherwise have faced. Moreover, during the short-lived Arab Spring of 2011-2013, Qatar tried to reshape the political landscape in the Middle East in its favor, challenging the two regional hegemons Saudi Arabia and Iran, in Egypt and Syria respectively. Yet, the paper concludes, geopolitical factors and the relative capabilities of states remain instrumental in assuring a state’s sustained capacity to continue playing a key role. This is particularly true in a region where elite thinking continues to be defined by realpolitik.

Keywords: Qatar Foreign Policy, The Gulf Crisis, Foreign Policy Strategies

The State of Qatar and its foreign policies and regional relationships have garnered much interest in both Arab and worldwide media. The country’s role in regional crises is met sometimes with critique and sometimes with praise, depending on one’s position toward the issue being dealt with. In academic circles, however, a far deeper discussion is taking place around Qatar’s regional role and its foreign policies, one which goes beyond simple political biases, ideological stances, and media coverage.

Here, Qatar represents an established case, attractive to researchers due to the challenge it poses to the most prevalent tenets of international political theory and their ability to explain interstate relations and foreign policy. International political theory, especially its various realist strands, is derived from the central notion that the international system is a system of great powers; that neither the existence or the foreign policy of small states is important because they are totally subordinate to the great powers1; and that these states, in order to survive in an environment characterized by chaos and governed by the notions of self-interest and self-sufficiency, necessarily adopt one of two approaches: either the state comes under the wing of a great power in a ‘bandwagoning’ relationship in order to protect itself against local threats; or it enters into alliances with other states to take on the threats posed by a stronger power, a strategy known as ‘balancing.’ 2

Qatar adopted both these strategies between the years 1971–2011: it entered into a relationship of dependency with Saudi Arabia to defend itself against Iran, especially after the Shah’s regime fell; then a protective relationship with the United States when it signed the 1992 Defense Pact and when after 2002 it began hosting US forces at al-Udeid Base to protect itself against Saudi threats and pressures; and again when it repositioned to become a formal member of the so-called “Axis of Resistance” between 2006–2011 to counterbalance Saudi pressure, which intensified following the American invasion of Iraq in 2003.

In the last two decades, Qatar has continued to receive intense media attention as a result of the effectiveness of its foreign policies and the disproportionately large role they have played in the region. Nonetheless, it has largely continued to operate within the established frameworks of small-state foreign policy: balancing or bandwagoning.3 Only with the Arab Spring did Qatar begin to present a true challenge to scholars of international relations. Since then, the Qatari government has shocked onlookers and, through its policies, has challenged the most important IR and foreign policy theorists and their ability to explain the behavior of small states in crisis situations. Whereas small states, especially in periods of unrest and uncertainty, tend to avoid any roles or policies which challenge the status quo—lest such measures jeopardize their safety and existence—Qatar has opted for the exact opposite route. It has adopted a leadership role, attempting to maximize gains and influence by pushing forth the wave of change that broke across the region and by encouraging democratic transition even though Qatar itself is not a democratic state.

This stance has complicated Qatar’s relationship with its two largest neighbors within the regional system. It entered into confrontation with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as a result of its support for the January 2011 revolution in Egypt against the regime of President Husni Mubarak, and with Iran as a result of the former’s support of the Syrian resistance against the regime of President Bashar al-Asad. This coincided with the shrinking of the US presence in the region in line with new priorities and interests and a reduced US commitment to maintaining the security of allied regimes. In other words, Qatar complicated its relations with its two largest neighbors at a moment in which it lacked sufficient guarantees of protection from the USA. During this period it seemed as if Qatar had suddenly given up on the strategies it had long used to protect itself and remain independent—bandwagoning and balancing—and adopted an offensive strategy in an attempt to forge a new regional system in which it holds a leadership role, a role which goes against the will and interests of the region’s great powers.

The period of 2011–2013 represented the peak of Qatari political activism and likewise the most challenging period to explain using IR theory. Qatar refused to remain in its allies’ shadows, seeking protection it saw no need for given the groundswell of popular protest across the Arab world. Rather, it attempted to take advantage of the opportunity presented by this groundswell in order to change the decades-old Arab political status quo. It refused to accept its rivals’ tutelage in exchange for security, believing that it had the upper hand in a vast conflict playing out across the region between the desire for change and the desire for inertia.

As a result, Qatar pursued an active and independent foreign policy both regionally and internationally, going so far as to intervene militarily in Libya, provide every kind of support to opposition factions in Syria, and back the Morsi government in Egypt politically and financially. During this time, Qatar not only opted to support democratic transition in the Arab World but indeed dominated the Arab political discourse around opposition in countries experiencing revolution, playing a prominent role in setting the terms of this discourse. Qatar thus transformed into a lead actor in many key regions of the Arab World, ranging from Syria to Egypt to Libya as well as its role in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Qatar took advantage of the atmosphere of fear and resignation that the traditional Arab regimes in power were experiencing in order to keep playing a central role in the regional arena, without regard for the reactions of regimes fighting a rearguard action, and to keep fighting for its survival. In this way, Qatar defied the most widely-accepted assumptions in international relations and foreign policy, namely the notion that small powers either obey larger powers in exchange for protection or enter alliances that aid their survival and independence. Qatar also challenged the prevailing assumption that material wealth discourages states, especially small ones, from adopting active foreign policies, and that the ruling elite in such states has only a limited role in making foreign policy compared to that played by systemic regional and international factors and the restrictions they impose.

Through the Arab Spring, Qatar adopted an offensive policy pursuing goals that seemed both illogical and impossible for such a small state. By exploiting its soft power (namely, media and wealth), Qatar jumped at the opportunity presented by Arab societies rising up against their despotic systems of rule. By doing this, it sought to reconstruct the Arab regional system in such a way that it would occupy a central role. Equally, the Arab Spring allowed it to confront the security dilemma presented by its two larger neighbors: Saudi Arabia by cultivating a regime friendly to Qatar in Egypt, and Iran by supporting the creation of an allied regime in Syria.

During this phase, Qatar attempted to establish itself as the architect of the new regional system taking shape on the ruins of an old system that seemed to be collapsing. This role – regulator of the regional balance of power – is unprecedented in the history of international relations and diplomacy for a state in Qatar’s position.4

This study examines Qatar’s role and foreign policy and attempts to highlight the strategies the Qatari ruling elite have pursued in the past two decades to deal with the structural challenges it has confronted and achieve the highest degree of independence in its foreign policy in a regional climate allowing little room for maneuver.

In this way, we hope to put the most prominent assertions of international relations and foreign policy theory to the test in explaining the relationship between actor and structure, and the role of strategies that the skilled elite employ which allow them to loosen the bonds of surroundings and geography and subject both to the achievement of its goals.

I: Theoretical Approaches in Explaining Foreign Policy: The Actor-Structure Argument

A country’s foreign policy is the product of the interaction between a set of factors and internal and external structures, an interaction which determines the set of options, policies and choices available to decisionmakers. These options are characterized by rationality and seek at a minimum to guarantee the state’s survival and preserve its independence and at maximum to dominate the particular regional or international system in which it exists. A state’s ability to achieve these goals and everything in between depend on its capacities and capabilities relative to other actors in its regional system. It also depends on the strategies, policies, and skills employed by Qatari decision makers, and on the internal and external circumstances and conditions that enable them to achieve their intended goals. In any particular temporal or special context, decision makers seek to choose one option or policy from those available, taking into account the various dimensions of the regional environment – whether political, military, social, economic, internal, regional, international, technological, environmental, or geographic.

The academic study of foreign policy is a relatively new branch of political science, having come into existence in the post-World War II period – in other words, at the same time as the realist international relations theories of Hans Morgenthau came to the fore, which had a significant impact on American political thought throughout the Cold War. Through these theories, Morgenthau attempted to offer a comprehensive explanation of the outward behavior of states that a) brought together the notions of power and national interest, and b) emphasized the role of the exterior environment in determining a state’s choices, based on its relations with other actors in its regional and international context, and its strength in comparison to theirs.5

In approximately the same period, the behavioral school came about, which attempted to give the social-scientific disciplines a larger scientific dimension by imitating methods used in the natural sciences. This allowed for the transition from the study of particular cases within general politics (including foreign policy) and toward investigating specific theories which would make possible the development of theoretical assumptions through cumulative frequency and inference. The behavioral school believed that if elites were to change, regardless of the extent to which a given state is institutionalized, this would in most cases lead to a change in the state’s policies, since each elite has its own vision and philosophy. But there has always been disagreement around the exact role that the elite plays in defining the choices and foreign policies of the state.6

It is thus possible to distinguish two main schools of thought in the study of foreign policy. First, there is the structural school and its various theories, which revolve around the idea that the state is the sole independent actor in foreign policy. The behavioral school, on the other hand, looks at foreign policy as part of the internal functions of the state, meaning that decisions are made by a political elite which takes them on behalf of the state. Here, the state itself cannot be a decision maker; because it is an abstract, non-material expression of other things, it is not considered an actor. Actors are those individuals who take decisions in the name of the state and on its behalf, according to their visions and philosophies, while keeping in mind the structures that surround them and lead them to prefer one policy over another.7

Graham Ellison’s study, first published in 1972, is the most famous classical text dealing with decision-making within twentieth-century foreign policy. The study documents the thirteen-day period in October 1962 (between 16-28 October) commonly known as the Cuban Missile Crisis—from the moment President John F. Kennedy was informed that the Soviet Union was on its way to deploying mid-range ballistic missiles in Cuba until the very end of the crisis, when the Soviets withdrew their ships in return for America’s withdrawal of its Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

According to Ellison, the American government had three possible choices with regard to the crisis: 1) to invade and annex Cuba before the Soviet missiles arrived, to prevent their deployment; 2) to conduct air strikes at the missile’s location after their deployment; or 3) to impose a blockade on Cuba to prevent the arrival of the Soviet ships carrying the missiles. Kennedy chose the final option. Ellison argued that Kennedy’s personality played a central role in choosing a particular policy decision; if the decision had been in someone else’s hands, perhaps a different choice would have been made and the crisis would have ended differently.8

Focusing on the role of the elite in producing foreign policy, most researchers argue that the central question here lies in explaining why some decisions are taken over, why some policies are enacted and others not. Why did the Soviet Union, for example, decide to deploy missiles in Cuba in 1962? Why did Hitler decide to invade Poland in 1939? And why did Saddam Hussein invade Kuwait in 1990? What is the role of a decision-maker’s personality traits, and to what extent to they affect the circumstances of the crisis? And do these circumstances push decision makers to take decisions they wouldn’t have taken in other situations?9 Equally, it is necessary to distinguish between foreign policy – which the state adopts or chooses – and the process by which it is made. This process may take many forms in terms of how decisions are made, discussions and deliberates are held, choices evaluated and policy implemented within state institutions or elite circles (individual, collective, institutional or bureaucratic decision-making, for example).

This study is not concerned with the process of how decisions are made in Qatari foreign policy (i.e.: how are decisions made within elite circles, and who makes them?), but rather with the particulars of those decisions; the reasons that lead Qatar to adopt a particular policy rather than others; the way in which it is able to implement them; and the way in which it approaches the structural challenges that surround it.

So, what are the strategies that Qatari decision makers have employed to mitigate their points of weakness and capitalize on their points of strength? How have they dealt with dangers and seize the available opportunities in their surroundings? How have they made use of their capacities in order to realize their goals, as represented in the pursuit of a foreign policy independent from the two larger states in Qatar’s vicinity (Saudi Arabia and Iran), and moreover to take on a regional role described in Western media and academia as “punching above its weight”?10

In attempting to explain Qatar’s foreign policy and the role of elite decision makers in loosening the restrictions imposed by the structure of the regional and international system, we must address the tension regarding the relative importance of the role of actor and structure in the study of a state’s foreign policy, which makes answering the question of why a given state adopts a certain policy and not another a very challenging mental exercise indeed. In this section, we will consider the most prominent theories that speak to the priority of structure over actor, and those which tend toward advancing the role of the actor (i.e. the elites). In the following section we will test what has been said against Qatari foreign policy in order to establish whether any of these theories possess the best explanatory power for Qatar’s behavior, regional priorities, and international relations.11

1. Structural-based perspectives

Structural-based perspectives tend toward minimizing the role of individuals and elites in producing foreign policy and, instead, focus upon the role of structure, whether material or social, in determining the behavior of states and their foreign policies. The most important theories are as follows:

a. Realism

Hans Morgenthau is considered one of the pioneers of the study of foreign policy in the twentieth century and his Politics among Nations is considered the seminal work in this field. The realist approach was expanded by Kenneth Waltz, notwithstanding his belief that IR theory is not interested in foreign policy because of its critique that he places excessive emphasis on structures and denies actors any importance. The foreign policy and behavior of states, for Waltz, are both completely subordinate to the forces and structure of the international system, according to the distribution of strength.12 As such, the international system is a system of great powers who set the regulations and draw the borders of others.13 But adherents of neoclassical realism among the students of Morgenthau think that the goal of the theory of international relations is, necessarily, to explain the foreign policy of the state.14

It is possible, within the framework of neorealism, to talk about two movements: one defensive, the other offensive.15 Offensive realism is best represented by John Mearsheimer who argues that, so long as the international system lacks a higher power, a law and the means to enforce it, and encourages conflict and warfare, states will continue to pursue their own safety in an offensive way regardless of the elites that rule them.16

Defensive realism, as represented by Steven Walt, among others, is not satisfied with this Hobbesian reading of the international system. It rather argues that the structure of the international system is not able by itself to explain a state’s behavior or foreign policy, even though it plays a large role in determining them. Instead of focusing on the distribution of power between states within this system, defensivists tend to emphasize the importance of the source, level, and direction from which states face a coming threat, according to the specifics which technology and geography and offensive capabilities undertake and to the intentions in a major role in determining states’ responses and foreign policies.17

Neoclassical realists align with neorealists on the notion that a state’s foreign policy is defined first and foremost by that state’s position within the international system and the power and capabilities it possesses. However, they stress that the impact of factors related to the structure of the international system on the behavior of states is less direct and more complicated than neorealists realize, as these factors affect foreign policy to a degree that reflects the domestic needs of the state and the interests of various powers within it, which are reflected in the decisions of elites who seek to achieve the state’s interests and goals.18

According to Steven Walt, domestic policies play the role of the variable which mediates the distribution of strength in the international system and in foreign policy.19 Because of his affirmation of the role of systemic and internal factors, he sees neoclassical realism as the theoretical framework most capable of tracing the effects of both domestic and international elements and combining them to explain states’ foreign policies20.

Overall, the differences between its various strands notwithstanding, realism tends to give much greater prominence to structural or systemic factors than to individuals or elites in explaining a state’s foreign policy because the logic of power (i.e. raison d’état) is its essence. ‘Structure’ here refers to the structure of the international system, as neorealism understands it, or a mixture of domestic power resources and international structures, as neoclassical realism understands it. In either case, the state is considered the principal actor and its capability to act is determined by material factors and their transformations whether within or without the state.

b. Liberalism

Although neoliberal institutionalism, like realism, is a structural-systemic theory with a similar top-down reading of the international system, partisans of this school contend that the ruling elite have a more significant role in creating a state’s foreign and security policy. Liberalism sees the state as the primary actor in the international system, an actor that behaves rationally as it attempts to maximize gains in an international system generally characterized by disorder.

Like realism, liberalism sees foreign policy as a limited set of options serving the interests of a strategically-minded state. However, liberalists do not see these limitations within a distribution of capabilities framework in the international system, as do realists. Rather, they understand them within the framework of the disorder inherent to the system, which although it produces a state of uncertainty and a security dilemma can also lead to the emergence of a regime or system of rules, traditions, laws, values and conventions that can produce a degree of international harmony and cooperation.21 These regulators play an important role in determining states’ behavior and in alleviating the international system’s tendency toward disorder.22 States’ inclination to protect themselves and seek their interests is softened through international institutions which take interest in the principles, traditions, regulations, laws, and customs that play a central role in refining state policies and behaviors.23 The more educated the elites are the more they tend to respect these principles and axioms.24

c. Constructivism

Constructivism argues that reality is a structure, or social construct, embodied in overlapping social principles and norms which shape our knowledge and understanding of that reality. How do we view the world, and how do we view ourselves within it? How do we determine our interests and the most appropriate way to further them?25 Ideas and values represent the building blocks of the social structure which is translated into the intended behavior of actors in a given society, just as it plays a principal role in forming actors’ identities and determining their actions.26 By challenging the basic assumptions on which the international system rests, constructivists argue that shared or agreed-upon ideas about acceptable state behavior leave a deep impact on the nature and work of international politics.27

By alluding to a particular model of foreign policy, the goal here is to work out how knowing how to encourage or discourage a particular behavior by means of factors related to prevailing notions; in other words, how to affect these ideas in the state’s understanding of the material world that surrounds it. According to constructivists, another factor is present which affects the behavior and foreign policy of states, closely tied to the first: identity, which plays an important part in explaining the socially-constructed nature of the state and its interests in such a way that “identities provide a frame of reference from which political leaders can initiate, maintain, and structure their relationships with other states.”28

Most studies that adopt the constructivist theory in explaining foreign policy tend to focus on the state identity component. Even though human social relations and interactions are considered essential to the process of producing and perpetuating values, ideas and identities, constructivism, much like realism and liberalism, is a theory which gives priority to structures over actors in explaining foreign policy. This is because it focuses on the social structure in which decision makers operate rather than on the characteristics, skills, and ideas of those decision makers. As a result, these theories come together in prioritizing structural factors over the role of actors or elites as the primary element which determines state behavior and foreign policy, even though they do not totally exclude the role of the actor from their analysis of foreign policy.

2. Actor-Based Perspectives

Unlike structural perspectives, actor-based perspectives tend to assign a larger role to elites in determining foreign policy choices, focusing on the skills, capabilities, and strategies decision makers use to surmount some of the structural obstacles to the achievement of certain goals and the realization of certain interests. The most important perspectives which give the actor a larger role in determining the foreign policy of states are:

a. Cognitive-Psychological Approaches

If the notion of the rational actor on which structural theories — particularly realism and liberalism — are based, supposes that leaders tend to adapt to the constraints which the system imposes upon them, then cognitive and psychological approaches are based on the opposite hypothesis. They argue that individuals’ behavior, impervious to constraints and influences, is the product of their attachment to their opinions, beliefs, and way of approaching information, to say nothing of other personal and cognitive characteristics.

Through a focus on the study of behavior and its transformations, which has been an axis of interest in sociological analytical studies in recent decades, the long-lasting idea of individuals as “malleable agents” began to be replaced by the idea of individuals as agents acting on their own initiative, as problem solvers.29 It became clear that the characteristics, ideas, beliefs, motivators, worldview, and decision-making methodology of the leadership strongly impact how choices are identified and decisions made in foreign policy. Here, the leadership could be an individual or a group of individuals.30

b. Neoliberalism

The neoliberalist perspective provides a critique of neorealism and neoliberal institutionalism based on three fundamental points of focus. First, it gives societal actors priority over political institutions and therefore focuses on a bottom-up model of the political regime instead of a top-down model; in other words, individuals and social organizations are more relevant to the making of decisions than political factors because they determine their interests independent of those factors and strive to achieve them by way of political bartering and collective action. Second, state choices and behavior represent the interests of particular communities within society. Leaders and politicians determine the interests and choices of the state and represent, in turn, the interests of powers and groups that exist within the state. They work within the framework of international politics in order to achieve their interests as they see them. Third, state behavior in the international system is determined through the overlap of a given state’s interests and choices with the interests and choices of other states, as determined by their respective elites and leaders.31

This theory differs from its counterparts in the sense that it focuses on the role of social groups instead of on those individuals who hold political authority. It thus advocates an understanding of foreign policy within a wider socio-political context than other perspectives.

c. Interpretative actor perspective

Like structuralism, the interpretive actor perspective calls for an understanding of actors as reflexive entities in a world of overlapping meanings. But unlike structuralism, which is based on explaining individual actions within a framework of norms, meanings, and social contexts, this perspective focuses on understanding foreign policy by examining the thought process and behavior of decision-makers. Here, the focus is on understanding political decisions from the viewpoint of those who make them, by deconstructing the reasons and motivations which drive them to take those decisions. “The foreign policy behavior of states depends on how individuals with power perceive and analyze situations.”32 In their study of decisionmaker behavior – chiefly in the United States, the former Soviet Union, West and East Germany, Britain, and France – during German reunification, Condoleeza Rice and Philip Zelikow conclude that if relevant decision makers had not thought in a particular way and made the decisions they did in actuality, the history of that period of time would be vastly different.33

Unlike structural theories, actor-based theories acknowledge the relevance of the role played by decision-making elites in determining state foreign policy, as they strongly impact the selection of options and the making of decisions through their ideas, ideological positions, and worldview. The political and diplomatic skills and leadership characteristics of decision makers also play an extremely important role in loosening the restraints imposed by structural and systemic factors on the decisions that, in their view, serve the state’s interests.

II: The Qatar Phenomenon

Many academics interested in the study of Qatar and its foreign policy acknowledge how difficult it is to explain its diplomatic choices using the major theories of international relations and foreign policy.34 Others have gone as far as to argue that this policy “defies explanation”.35 This confusion has driven some to take the opposite approach entirely and say that it is Qatari foreign policy itself that lacks cohesion and this is why it is so difficult to account for.36 Still others have argued that Qatar has merely made use of its vast financial capabilities to preserve its security and to extract international and regional recognition of its role.37 Although efforts to exercise autonomous decision-making are the primary driver of Qatari foreign policy,38 this policy has in fact transformed into a survival strategy according to this viewpoint.39

Between efforts to ensure its survival and realize its autonomy in a politically tumultuous and insecure regional context, and efforts seeking greater recognition of its influence and adoption of a significant regional role, most studies dealing with Qatar’s foreign policy and diplomatic choices seem somewhat conservative, offering a comprehensive explanation placing it in a framework of duality: of strategy and geography, of actor and environment, of the structure of the regional and international systems, of the skills of decision-makers and their ability to address challenges. This clearly reflects how confused the theoretical principles become when approaching an exceptional case such as the one Qatar poses to international politics. Few theories have taken note of the Qatari case, either because they do not consider the role of small states in the first place or attribute to their policies a high degree of importance in the structure of the international system, or because a similar case commanding a comparable degree of academic interest has not come about in the past.40

Contrary to popular understandings of the behavior of small states, Qatar adopted a strategic, offensive foreign policy to preserve its safety and defend itself in an environment with larger, more powerful actors. This action, in and of itself, represents a challenge to both structure-based and actor-based IR and foreign policy theories. As previously noted, all these theories see small-state foreign policy as one of two basic perspectives used by smaller states to protect themselves and survive should they find themselves unable to remain neutral toward large neighboring powers: forming alliances with other powers in their regional systems to confront a larger power, as southeast Asian states have done to face China; or joining a larger power who takes care of protecting them in exchange for absolute submission, as Bahrain has done in its relationship with Saudi Arabia to confront Iranian ambitions towards its land.41

Qatar did not have the option to stay neutral given the conflict the region was witnessing, especially after the revolutions of the Arab Spring unfolded. Moreover, the prevailing political culture of the region, within which “Realpolitik” reigns supreme in the thinking and behavior of ruling elites, precluded Qatar remaining neutral. The Middle East and Gulf regions still operate according to European norms of conflict in the 19th century, rooted in the notions of power and hegemony. They have not been able to leave these norms behind and transition to the liberal dispensation that has prevailed in Europe since the end of the Second World War, a dispensation based on the principles of collective security, interdependency, and shared interests such that small states are protected against tendencies towards hegemony thanks to the ascendancy of a legal system regulating interstate relations.

Beyond its inability to be neutral, Qatar has been attempting to rid itself of Saudi hegemony over its own foreign policy since 1995. This has led both to the deterioration of its relations with Riyadh and its abandonment of a strategy of either joining with or submitting to the Kingdom’s will. Even after agreeing to host the American military base in al-Udeid in 2002, Qatar remained was exposed to Saudi pressure, particularly military pressure.

Although Qatar has at times pursued a policy of balancing Saudi influence in order to ensure its independence – drawing closer to what was once termed the “Axis of Resistance” (Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, and Hamas) between 2006 and 2011, for example – it quickly abandoned this policy with the eruption of the Arab Spring revolutions (2011). At this point it entered direct confrontation with Iran in Syria and with Saudi Arabia in Egypt, even as Washington was withdrawing from the region following two failed wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, uninterested in further intervention.

In the period between 2011 and 2013, it may be said that Qatar did not have available any choices smaller states traditionally employ to survive and stay independent. Not only that, it also adopted an aggressive policy by which it forced its large opponents onto the defensive, making use of the power of the streets and the unbridled desire for change to advance and take on a leadership role in the construction of a new regional system in which it might play a central part. In doing this, Qatar represents an exceptional case in the field of public policy and theoretical studies concerning the foreign policy of smaller states.

III: The Problem of Geography and Qatar’s Security Dilemma

Napoleon Bonaparte is said to have commented that “to know a nation’s geography is to know its foreign policy”.42 It is thus important to consider Qatar’s geography (the fundamental determiner for state behavior, according to structural perspectives) in order to a) grasp the extent of its impact on Qatar’s foreign policy and the role it aspires to play regionally, and b) to test the contention of the most prominent IR theories that the state and its foreign policies are hostage to the environment in which they exist. What, then, is the nature of the environment in which Qatar finds itself today?

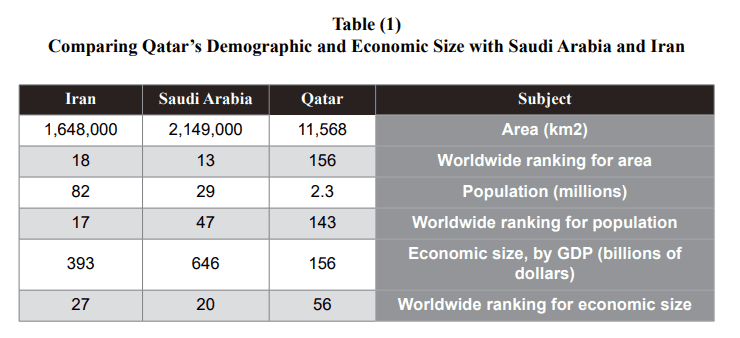

Qatar is a small country, even by the standards of the Gulf and Middle East. It lies at the very tail end of the list of countries of the world in terms of geographic size (165th)43 with an area of 11,586 km2. It is a peninsula on the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, spanning roughly 160 kilometers from north to south, and 80 kilometers from east to west. Its population is 2.3 million, 280,000 of whom are Qataris (12% of the total), and it ranks 143rd in the world in terms of population. 44

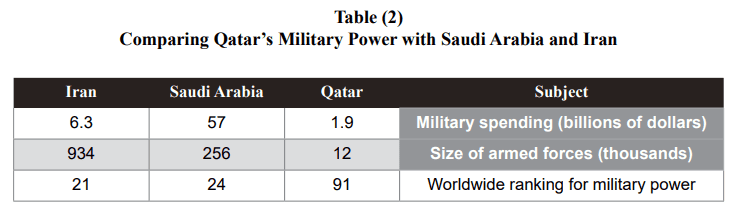

Qatar comes in 91st place worldwide in terms of military power, with its armed forces not exceeding 12,000 persons occupying various roles in total.45 In 2016, Qatari military spending totaled $1.9 billion; given that the size of its economy was $156 billion, this places it in the 56th rank worldwide.

Qatar lies between two large neighbors, Saudi Arabia and Iran. Saudi Arabia (13th in the world in terms of area46, reaching 2.149 million km2 and 47th in terms of population, with 29 million people47) holds a total monopoly on Qatar’s land borders—its border with Saudi Arabia, about 60km long, is its sole land border. Saudi Arabia is more than 200 times larger than Qatar geographically and 100 times larger in terms of population, and the Saudi economy is more than three times larger than the Qatari economy, with a GDP of $646 billion according to 2016 World Bank numbers, and it occupies the 20th rank worldwide. According to Global Firepower, Saudi comes in 24th worldwide in terms of military power. Its armed forces are composed of 256,000 persons across various branches. Saudi military spending in 2015 reached $87 billion, although it shrank to $57 million in 2017 (see table 1) 48.

Iran, Qatar’s neighbor on the other side of the Arabian Gulf, is the 18th largest country worldwide by size, spanning 1.648 million km249, and the 17th in terms of population with 82 million.50 It strongly impacts Qatar’s surroundings in terms of the sea (if we exclude from the equation small Bahrain, at a mere 765.3 km2). Iran is 170 times larger than Qatar and its population nearly 400 times bigger. The Iranian economy is two and a half times larger than Qatar’s with a GDP of $393 billion in 2016, placing Iran in the 27th rank worldwide in terms of economic size.51 It is placed in the 21st rank in terms of military power given its armed forces composed of 934,000 persons between active duty (534,000) and reserve (400,000); its 2016 military spending was approximately $6.3 billion52 (see table 2).

In addition to these significant differences in what is traditionally thought to make up military power between Qatar and its neighbors, the country has a dry, desert climate with minimal subterranean water and nonexistent surface-level water. This reality makes agricultural and industrial development more difficult. This challenging situation, geographically and politically, means simply that Qatar not only lacks the necessities for traditional power in the international system (large area, large population, and an advanced agricultural and industrial base), but also lies between two large powers competing for control of a regional system experiencing widespread unrest, facing off through wars, both proxy and direct, in more than one place throughout the region.

Since 1979, Iran and Saudi Arabia have been in intense conflict for influence, regional hegemony and the ability to decide the rules of play within the Gulf region. The Shah of Iran had a relatively good relationship with Saudi Arabia because they shared a common alignment within the Cold War and because they were both monarchies that looked to the West as a model and protector. With the Shah’s fall, however, a revolutionary Islamic republic that adopted a policy of exporting its model to other countries was established. Saudi Arabia saw Iran’s revolutionary Islamic model as a major threat both to its safety and to the legitimacy of its regime, model, and claim to leadership of the Islamic world, deriving fundamentally from its guardianship of the holy sites of Islam.

All the other Arab Gulf states shared Saudi Arabia’s fears of Iran, forming the regional alliance known as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) following the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War. The alliance was announced in May 1981, with six Gulf states joining together as part of an ambitious project to build up shared defensive capabilities and to achieve economic integration and political coordination, based on the many things these states have in common and their shared sense of impending danger from the other side of the Gulf. During the eight years of war Qatar held to GCC’s consensus of opposition to Iran and support for Iraq.53

It might be said that until the 1990s Qatar had no foreign policy of its own but was dependent on Saudi Arabia and totally reliant upon it for protection from larger powers in the regional system (i.e. Iran and Iraq). Until this point we can thus say that Qatar pursued a bandwagoning strategy through the GCC, whose basic goal at its establishment was to confront the threat posed by Iran to conservative Gulf states post-revolution.

However, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 shocked all the small Gulf states, most of all Qatar, and showed how fragile depending on Saudi Arabia was: it became clear that Riyadh demanded the privileges of leadership without being able to meet the protection requirements of the smaller states of the Gulf regional system. The Iraqi invasion also broke the taboo in Arab politics of an Arab state attacking and annexing another. Qatar’s concern that Saudi Arabia might follow the Iraqi example in the Qatari-Saudi border dispute that began in 1992 created a sense that its survival as a state (and not just that of its ruling regime) was in danger. Indeed, Saudi Arabia – where an expansionist doctrine with designs on all the Gulf states (and Yemen) dominated – attacked and occupied the Qatari Al Khufoos Border Crossing, deepening Qatar’s fears of its larger neighbor.

With Iraq’s departure from the regional equation after the 1991 Gulf War, Qatar began to think about an independent foreign policy, attempting to follow a balancing strategy in its relations with its two large neighbors so as to ensure its safety. After the Iraqi invasion, Saudi Arabia was no longer only an insufficient guarantor of security, it was also a potential threat. But Iran, with whom Qatar shares the largest natural gas field in the world (South Pars/North Dome), also provided cause for concern. Although Tehran staked no territorial claim to Qatar (as in Bahrain, inhabited by a Shi’a majority that Iran exploits to undermine the ruling regime), Iranian policy has nonetheless been a constant source of anxiety for Doha. Iran strives to dominate as part of a regional venture through which it is working towards exporting its model and imposing a kind of protection and dependency on Shi‘a living in Gulf Arab states.

Even though Qatar is home to only a small Shi‘i minority, who enjoy the same rights and responsibilities as other citizens, Iran’s policies and inclinations towards exporting the revolution and upsetting the security of conservative states allied with the West on the other side of the Gulf are still a source of anxiety for Qatar.

As a result, Qatar finds itself, by virtue of geography, between two large regional powers competing for dominance over the area – neither of which will accept anything short of full support for their policies in the region from Qatar. Saudi Arabia is a status quo power, while Iran is a revisionist power. Qatar, searching in its turn for a regional role far away from the domination of these two regional giants, had to adopt strategies to overcome this difficult geopolitical reality in order to ensure its survival and a minimum level of freedom of action and seek to acquire a regional role that satisfies its ambitions as much as possible without its existence being put at risk. This is because both its large neighbors are of the opinion that the role Qatar detracts from their own influence and is contrary to their interests, to say nothing of the fact that Qatar’s size does not permit it in the first place, according to this view, to win any role or influence within a regional framework governed by power and overpowering.

IV: The Elite in Confrontation with Structure

As noted, the issue of elites and their role in international relations and foreign policy occupies a central position in theoretical discussions in this field, such that most researchers who talk about the importance of the role of leadership in forming foreign policy have tended to argue that freedom of choice among decision makers depends largely on their ability to subjugate their surroundings, or at least to limit the restrictions their surroundings place on their freedom to choose from available policy options.54

Robert Jarvis argues that the difference between decision makers with and without particular skill lies not in their policies, but rather in their ability to achieve their objectives through a) a close reading of regional and international variables and winning local popular support for their policies and b) building alliances that serve their goals and interests.55 Possessing these political skills allows some decision makers to pursue objectives more effectively than others, benefiting from the options and information available to them.56

It is no longer possible to deny the extent of the impact leaders – through their opinions, thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors – have on the process of decision making with regard to state behavior and foreign policy.57 Despite this, when the question of the importance of leadership in determining small-state foreign policy in the international system is posed, we find that the theoretical entry points which revolve around the notions of power and influence give the impression that they have not had a major impact, as the foreign policies of smaller states are generally understood to be the result of the interaction between pressures applied upon them by larger states in the regional and international system and their attempts to protect their independence and national identity.58

Thus, many small states find themselves in a state of constant self-defense justified by their sense of insecurity in an international system in which disorder prevails, which pushes them toward forming alliances with larger powers to ensure their protection, or perhaps toward adopting foreign policies with a defensive character in coordinating with other small powers to achieve a degree of balance with larger powers.59 However, security dilemmas are by no means limited to smaller states; all states in the international system, including great powers, face this problem, albeit to differing degrees of intensity. We thus cannot but conclude that the extent to which a state enjoys power and influence is not directly correlated with its geographic size or military might; indeed, how else are we to explain a state of Qatar’s size attempting to exercise influence on a state the size of Egypt?

The reality of the situation is that the studies that deal with small-state foreign through the conceptual framework of power and influence within international relations generally speaking take us further than the familiar ideas of classical realism. One study considering the factors determining the building of alliances between small states shows that these alliances in essence show “the ability of these states to achieve desirable results” in foreign policy, which leads one to emphasize additional factors beyond “the basic components of power”; “more comprehensive elements of state power” ought to be taken into account instead, including the quality of leadership and the skills it possesses.60 As such, we find that “smaller states might achieve their goals in spite of their objective lack of the material influence necessary for that end”, and that this kind of success must be taken into account when looking at the foreign policy of a state. Studies that have examined the behavior of small states during the Cold War have suggested that “the ideas, beliefs, preferences, and interests of elites” have at times played a larger role in determining the nature of relations with the West and Russia than have factors related to the structure of the regional and international system. Similarly, it may be said that elites have played a major role in determining Qatar’s foreign policy and are now able, by virtue of the skills they cultivated and the strategies they employed, to minimize the importance of structural factors which, had they been accepted without question, would have led Qatar to follow a less independent and significant foreign policy within its regional system. What, then, are the strategies the Qatari elite have employed to achieve its foreign policy goals?

V: Strategies of the Qatari Elite to Confront Structure

Structural factors particular to the regional and international systems play an important part in determining the characteristics of Qatari foreign policy. This is a general feature of all states large and small, but this policy cannot be deeply understood without a familiarity with how the Qatari elite thinks about and imagines these factors and challenges, and the ways in which it deals with them to either neutralize them or minimize their importance. In fact, it may be said that the endeavor to expand Qatar’s regional role and facilitate its recognition results from the way Qatar’s decision makers see the position of their country within the region and the world, given that Qatar’s foreign policy changed radically when the ruling elite changed in 1995.61

It is true that Qatar began to search for a solution to its security dilemma which ensures its survival in the face of the worsening threats it faces in its regional context outside of the GCC framework since the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. However, its attempt to play a regional role and win recognition for it and the subsequent transformation of this goal into a higher state strategy, in confronting external threats and as a means to protect its independence and avoid dependency on its two large neighbors, took place only with the arrival of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa to power in June 1995, which reaffirmed the role of the elite (i.e. the actor) in determining Qatar’s foreign and regional policy. Most importantly, it may be inferred that the skills and political abilities of elites and the strategies they employ have played a significant part in neutralizing structural factors and the limitations imposed by geography such that a greater regional role may be taken up.

As such, Qatar’s foreign policy cannot be analyzed or its regional role understood without considering the personal dimension and the thinking of the decision-making elite. It is notable that during this period, many studies concerned with foreign policy are placing increasing importance on the role of elites in determining foreign policy choices, importance that appears clearly when a regime changes—whether by way of natural development (i.e. the cycling of elites and the progression of generations) or by way of forcible change (i.e. revolution or coup). With the advent of a new administration, individuals tasked with upper- and mid-level decision-making change. It also tends to be the case that the new administration brings with it an intellectual and philosophical orientation different from that of its predecessors.

The massive transformation in Qatari foreign policy began, therefore, with the arrival of a new administration in June 1995. The change in Qatar’s foreign policy can be observed by tracing the change in decision makers. During Sheikh Khalifa’s reign, Qatari foreign policy was almost totally controlled by systemic factors in accordance with the structure of the regional system, especially geographical determinants, which played a central part. Things changed after 1995 in that Qatari decision makers began attempting to take structural factors out of the equation, or at least to minimize their ability to impede the achievement of their goals and the execution of their policies, by adopting specific strategies to assist in this endeavor.

The new elite adopted an active foreign policy that furthered their political and economic interests and their ambition to take on an influential role in the region. The vision of the new leadership had a distinct anti-status quo orientation which became clear through the media and in a foreign and economic policy which sought to extract the utmost benefit from the country’s wealth and natural riches and to employ them to serve a foreign policy agenda. Since 1995, therefore, Qatar’s foreign policy has begun to clearly reflect its national interests, the ambitions of its regional leadership, and the country’s security needs. Before this time it can be said that Qatar lacked a foreign policy of its own.

As part of its vision for the role and positioning of its country in regional and international politics, and in order to formulate suitable strategies to overcome structural limitations, it was necessary that the new Qatari elite analyze its surrounding external environment and probe its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and risks. The primary structural challenge identified by this analysis is Qatar’s small geographic area and population and in the fact that the country exists between two large regional poles, both of which seek to suck Qatar into their orbit, amid an atmosphere of fierce competition, instability, and elevated risks which would not permit Qatar to adopt a neutral stance.

Faced with this massive challenge, Qatari decision makers had to find a suitable strategy to help them adopt a foreign policy independent of the influence of those two regional poles, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Those decision makers, as rational actors, attempt at minimum to remain independent and at maximum to enjoy an influential regional role in an environment characterized by disorder and lacking both a hierarchy to govern state behavior and a higher power to rein in foreign policy; everything is decided by way of the distribution of power and capabilities within this system of chaos. Qatari decision makers adopted an offensive strategy considered unorthodox for a small state jammed between two giants. This strategy rests on the foundation of an active foreign policy which is not only able to achieve for Qatar the security it seeks where its hard capabilities are unable to do so, but which may also able to pay political and economic dividends as well. Moreover, Qatar is able to generate expansive political legitimacy from sources considered nontraditional in tribal societies, primarily resulting from external achievements added to its success in safeguarding higher levels of comfort and luxury for its citizens.

This ambitious strategy can only work when the appropriate possibilities are available. In exchange for the many points of weakness with which Qatar is afflicted, there were points of strength and opportunity ready for use allowing Qatar to transition from the position of a small power to that of a middle power. Geography, which has deprived Qatar of the massive area, large population, and water resources necessary for agricultural and industrial prosperity (i.e. the traditional sources of power) and jammed it in between two much larger forces, has in exchange granted the country massive energy reserves. Qatar possesses the third largest natural gas reserves in the world, following Russia and Iran (more than 24 trillion m2) and it is the largest producer of liquefied natural gas in the world with a productive capacity reaching 77 million tons each year and on the rise towards 100 million tons.62 By virtue of its income from the export of gas, Qatar occupies the 56th rank worldwide in terms of GDP, and because of its small population occupies the first rank worldwide in terms of each person’s share, with an annual per capita GDP of $129,000.63

These massive financial resources, which came as a result of massive investment in the extraction and processing of liquefied natural gas in tandem with the rise of an elite with a vision and strategy toward transforming Qatar from a small, dependent power into a middle regional power with an independent foreign policy and active regional role, have represented Qatar’s greatest strength in taking on an environment which prior to that was the fundamental and sole determiner for Qatar’s regional role, its international relations, and its foreign policy. Qatar’s financial independence was the first and most important step toward making its foreign policies independent of Saudi Arabia.

In order to be able to pursue independent policies, Qatar began to lean towards a balancing policy in its relationships with Saudi Arabia and Iran. Of course, such behavior necessitated the end of the bandwagoning policies Qatar had adopted vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia since its independence in 1971, just as it required Qatar to draw slightly closer to Iran. With each step Qatar took towards Iran, it took an equal step backwards and away from Saudi Arabia, eventually reaching the desired point of balance in its relations with its two neighbors. It compromised on its sea border disputes with Iran64 and closed a security agreement in 2010 on the issue.65 During this period, the so-called golden rule of Qatari foreign policy became apparen: Qatar’s ideal situation depends on the construction of good, balanced relations with its two large neighbors. In case it were to fail to do this, Qatar could indeed exist in a state of bad relations with one of the two. Nevertheless, in all cases, it is imperative to avoid bad relations with both at the same time, as this would pose a massive risk to Qatar.

From the beginning, Saudi Arabia rejected the new situation arising from the attempt by Qatari elites to adopt a policy of greater independence from the Kingdom. As such, from the moment he came to power Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa faced strong opposition to his rule and policies from Riyadh, who argued that the new Qatari royal was leading a rebellion against it and distancing his country from Saudi Arabia with his policies. For this reason, Saudi Arabia supported two attempted coups to remove Sheikh Khalifa from power in 1996 and 2002.66 Riyadh also opposed the construction of pipelines to transport Qatari natural gas to Kuwait and Bahrain.67 These lines were a fundamental component of Qatar’s strategy of developing its natural gas industry and strengthening its financial position and share in the world energy market.68

Saudi Arabia’s hostile stance drove Sheikh Khalifa to take up a mixture of active defensive and offensive strategies that included establishing balances and building alliances. These strategies included using the available tools of soft power—mediation, media, culture, thought, financial aid, charitable and humanitarian work; general diplomacy; sports; and founding worldwide partnerships and investments—to make Qatar a part of the world economic order, to transform it into an indispensable center of natural gas production,69 and to forge relations with internationally unwelcome powers and entities70 such that it and the necessity of its active political, economic, intellectual, and media role have become the most important tools to ensure its stability.71 It is an unorthodox strategy which seeks to lay the foundation for the state’s “brand” in order to ensure its security, engendering a certain interest in maintaining its independence among the quarreling powers of the region and the world.72

Qatar’s moment came in 2002 when it offered to host American forces following Riyadh’s request that they vacate the Amir Sultan base in al-Dhahran, after relations between the two parties worsened because of the attacks of 11 September 2001. This was a component of a wide-reaching strategy taken up by the new Qatari elite to overcome the security dilemma Qatar faced in its relationship with Saudi Arabia. Despite hosting the American base and having signed a defense pact with Washington in 1992, it is difficult to argue that Qatar was following a bandwagoning policy in its relations with Washington. Qatar simultaneously adopted foreign policies both in support of and against the United States at the same time,73 especially after 2006 when Qatar became an unofficial member of the “Axis of Resistance” led by Iran and including Syria, Hezbollah, and Hamas. At nearly the same time, Qatar started pursuing close relations with Turkey which reached a strategic level of economic, political, security, and military cooperation.74

Moreover, Qatar, which was naturally bereft of sources of hard power, began to tend towards a compensating strategy based on the use of soft power tools to realize its ambitions by competing for a regional role with larger powers. Foremost of these means was the media, which to Qatar is the most important weapon in confronting challenges and threats, such that it assisted in producing a special brand with a bigger role in making Qatar a relevant player in regional politics and in drawing international attention.

For many decades, the Arab World lacked non-state media bringing reputable news reports to the masses. Qatar’s decision to invest in that sector by launching Al Jazeera in 1996 sparked something close to a revolution in the Arab World, a region which had never experienced such a form of media in the past; it had long been dependent on Western Arabic-language media, such as BBC, Monte Carlo, Voice of America, and so on, in order to freely access news about and discussions around sensitive political issues.75

Al Jazeera represented Qatar’s largest investment in foreign policy; it has become the State’s primary means of realizing its ambitions of taking up a regional role. Al Jazeera has become a major player not only in its regional context, but in international politics as well. As a result, it has been subject to closures and harassment by many Arab regimes and, indeed, the target of missile strikes the Americans carried out against its delegations and offices in Afghanistan and Iraq.76

During this period, Qatar also succeeded in making itself an accepted mediator in various Middle Eastern conflicts. Qatar has acted as mediator between Fatah and Hamas more than once since Hamas’ victory in the 2006 legislative elections and subsequent takeover of Gaza opened a rift between the two movements. Qatar also provided mediation in the conflict between the Yemeni president Abdullah Saleh and the Houthis during the six wars the two sides fought between 2003-2009 and in various Sudanese conflicts from Darfur to the war with South Sudan. Its greatest success in the field of mediation, however, was bringing an end to the Lebanese presidential crisis which started with the end of President Émile Lahoud’s term in November 2007 and continued until Hezbollah invaded Beirut in May 2008. Qatari mediation between Colonel Muammar Gadhafi and Western states helped to solve the “Lockerbie Crisis” during which Western states accused the colonel of being responsible for the explosion of an American passenger jet over Scotland in 1989.77 It has also facilitated dialogue between the United States and the Taliban, constructing an office for the latter in Doha to facilitate communication between both sides.78

When the Arab Spring revolutions broke out, Qatar gave up the balancing strategy which it had been pursuing vis-à-vis its larger neighbors, especially when competition between the so-called “Axis of Resistance”, headed by Iran, and the “Axis of Moderation”, headed by Saudi Arabia and Egypt, sharply increased following the 2006 July War in Lebanon. In the period between the 25 January Revolution and the military coup of July 2013, Qatar decided to support the rising Arab revolutionary tide and confront Riyadh and Tehran, who both strongly opposed it. It intervened militarily on the side of NATO to upturn the regime of Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi,79 offering material, diplomatic, and media support to the Egyptian revolution in a stark challenge to the will of Saudi Arabia, who had taken a firm stance against the revolution in Egypt and worked to snuff out what came of it.80 Qatar, conversely, stood firmly with the revolution in Syria against the regime of President Bashar al-Asad and offered the Syrian opposition all forms of material, political, and military support in another challenge to the will of Iran, who in turn stood with the Asad regime.81

Qatar, in this period, relied on the power of this Arab revolutionary tide and on its relations with moderate Islamic powers and movements which appeared to be better candidates for holding power in the revolutionary countries than their counterparts due to their organizational abilities and their opponents’ weakness.82 Qatar also depended on its relationship with Turkey, who maintained the same policy towards Syria and Egypt in particular, and on the American position, which seemed willing to accept Islamist rule and humor the popular will as expressed in the voting booth as evidence of the coexistence of Islam and democracy and as a way to further isolate radical Islamist movements.83

However, systemic factors – Saudi Arabia and Iran’s positioning against the Arab Spring revolutions and the failure of the Obama administration to take up a clear policy to enable and defend those movements – aside from many other reasons, led to the ebbing of the revolutionary tide. This also foiled Qatar’s strategy of building on the desire for change expressed by the Arab people in spring 2011 in order to undermine the structure of the existing regional order – based since the creation of the modern Arab states after WW2 on unchanging, narrow, elitist, unrepresentative rule – and move towards a new order based on the will of the people.84

These failures drove Qatar to reexamine its foreign policies and regional relationships, especially with increased Saudi pressure following the success of the military coup in Egypt; this pressure reached a high point during the diplomatic crisis of early 2014. Another reason for this reexamination was the growth of Iranian influence, especially following the Houthi takeover of Sanaa in September 2014 and the retreat of the United States (which was inclined to let the regional conflict between revisionist and status-quo powers run its course without any major intervention – its attention was focused on establishing consensus around Iran’s nuclear program).85

During this phase, with the transition of power from Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa to his son, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad, Qatar’s focus returned to internal affairs and its regional foreign policy became less intensely activist. The country also attempted to resume the role of mediator in regional and international crisis. As Iranian influence grew, Qatar sought a closer relationship with Saudi Arabia. It joined the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen and sent forces to the country’s southern border. It also ceded leadership in the Syria conflict against Iran to Riyadh, which became apparent when the latter began to oversee formation of a Higher Negotiations Committee (HNC) subsequent to the Syrian opposition’s Riyadh Conference (December 2015).86

From early 2015 to mid-2017, Qatar seemed to have resumed its pre-1995 bandwagoning policy vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia. But the crisis that began suddenly in June 2017 showed that Qatar remained committed to an independent foreign policy despite intense pressure. A land, sea and air blockade was imposed on the country. Qatar responded by a return to a balancing policy in order to confront Saudi pressure. It invested in its relations with other regional poles, choosing this time to focus on Turkey (which had sent armed forces to Qatar under the 2014 agreement).87

The 2017 crisis highlighted once again Qatar’s political-geographic dilemma and how difficult it is for a small state attempting to preserve its independence against larger neighbors to overcome systemic political-geographic and regional-structural determinants. But it has also shown that these geographical determinants and systemic factors are not a death sentence for small states so long as they possess elites capable of inventing different strategies to acclimate to the challenges imposed on them by this structure or environment which they are unable to change.

It may be said that Qatar, because of its awkward geopolitical situation, developed its own survival strategy. When it faces pressure from Iran, it grows closer to Saudi Arabia; when Saudi Arabia is the source of pressure, Qatar balances it by growing closer to Iran. However, when the opportunity is available, due to simultaneous Saudi and Iranian withdrawal, Qatar abandons these two strategies and behaves offensively to increase its gains. This is precisely what took place between 2011 and 2013.

Conclusion

In their attempts over the last two decades to pursue an independent foreign policy and create an impactful regional role, the Qatari elite have clashed with a geopolitical reality that they cannot change or control (given that states do not choose their geographical environment or the structure of the regional order in which they exist). But Qatar has also discovered that it is able to invent strategies inspired by advances in technology and ideas (soft power) to maximize its strengths and mitigate its weakness (rooted in the presence of larger powers around it). Its elites have also benefited from the unique characteristics of the regional order within which Qatar exists: the prospect of benefitting from major conflicts between the poles of that order and its strong built-in resistance to the hegemony of any single regional power.

The intersection of financial resources and the existence of an ambitious ruling elite with a vision and high level of dynamism in making it a reality have allowed Qatar to greatly delimit the impact systematic factors have on its foreign policy and ability to play an influential role in the region. Qatar has thus been able to overcome some of its structural weaknesses, compensating for them with soft power tools and parallel strategies of two kinds: defensive, focusing on curbing the danger posed by its power-hungry enemies and defeating them; and offensive, expanding its sphere of influence further into the region.

On one hand, Qatar has formed a network of regional relationships that have helped mitigate the security dilemma posed by Saudi Arabia’s refusal to allow it political independence. It has counterbalanced Saudi pressure at times with Iran, at times with Turkey, and at times both at the same time. On the other hand, Qatar developed the instruments of its soft power, which played an important part in serving the goals of its foreign policies. By making use of the absence of an Arab media that enjoys any degree of freedom and the decline of the Arab cultural and intellectual capitals (in Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, and Beirut), Qatar endeavored to become an alternative intellectual, cultural, and media hub.

It has also worked – with variable success – to develop a reputation (i.e. brand) as a mediator in international conflicts, establishing a wide network of civil society and humanitarian organizations which worked to minimize poverty and neglect in various parts of the world. In this, Qatar became capable of constructing a positive mental image of itself by transforming its role into one aimed at regional and international interests and needs.

These are the strategies that Qatari decisionmakers have used to mitigate structural factors and the limitations they impose on its ability to follow an independent foreign policy and take up an active regional role between larger regional powers. In doing so, they offer a model which supports a perspective of the importance of leadership in determining a small state’s foreign policy despite the challenges of its environment, whether as relates to the state’s long-term goals or to its crisis decision making.88

An earlier version of this paper was published in AlMuntaqa, a peer-reviewed English-language journal dedicated to the social sciences and humanities, and published by the ACRPS.

Endnotes

1 Kenneth Waltz, “Reductionist and Systemic Theories,” in: Robert. O. Keohane (ed.), Neorealism and its Critics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), p. 63; Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1979).

2 Stephen Walt, The Origins of Alliances (London: Cornell University Press, 1990).

3 Stephen Walt, “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power,” International Security, vol. 9, no. 4 (1985), pp. 3-43.

4 Although numerous studies on small-state foreign policy exist, none presents the same sort of challenge to prevailing orthodoxy that Qatar does. See for example:

Miriam Fendius Elman, “The Foreign Policies of Small States: Challenging Neorealism in its Own Backyard,” British Journal of Political Science, vol. 25, no. 2 (April 1995), pp. 171-217; Peter R. Baehr, “Small States: A Tool for Analysis?” World Politics, no. 3 (1975), pp. 456-466; Robert O. Keohane, “Lilliputians’ Dilemmas: Small States in International Politics,” International Organization, no. 23 (1969), pp. 291-310; Robert L. Rothstein, Alliances and Small Powers (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968); Annette Baker Fox, “The Small States in the International System, 1919-1969,” International Journal, no. 24 (1969), pp. 751-764; Eric J. Labs, “Do Weak States Bandwagon?” Security Studies, no. 1 (1992), pp. 383-416.

5 Hans Morgenthau, Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 6th ed. (New York: Knopf, 1985).

6 Walter Carlsnaes, “Actors, Structures and Foreign Policy Analysis,” in: Steve Smith, Amelia Hadfield & Timothy Dunne, Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 115.

7 Hudson, V. M., Foreign Policy Analysis: Classic and Contemporary Theory (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), p. 6.

8 G.T. Allison & P. Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd ed. (New York: Longman, 1999).

9 Ibid., pp. 2-3.

10 Joost Hiltermann, “Qatar Punched Above Its Weight. Now It’s Paying the Price,” The New York Times (June 18, 2017), accessed on 2/10/2017, at: https://goo.gl/xMBb8G

11Whereas studies that deal with the process of decision making in foreign policy tend to agree on the importance of the Actor and Structure factors together, without preference for one over the other, as a way to escape the dilemma of responding to this question; see also: Carlsnaes, “Actors, Structures and foreign policy Analysis,” p. 118.

12 Kenneth N. Waltz, “Structural Realism after the Cold War,” International Security, vol. 25, no. 1 (Summer 2000), pp. 5–41.

13 Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959).

14 Carlsnaes, “Actors, structures, and foreign policy Analysis,” p. 119; Jack Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambitions (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), p. 20.

15 Gideon Rose, “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy,” World Politics, vol. 51, no. 1 (October 1998), pp. 144-172.

16 John J. Mearsheimer, “Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War,” in: Michael E. Brown et al. (eds.), The Perils of Anarchy: Contemporary Realism and International Security (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), pp. 78-129.

17 J. Taliaferro, “Security Seeking Under Anarchy, Defensive Realism Revisited,” International Security, vol. 25, no. 3 (2000), pp. 128-161, accessed on 2/10/2017, at: https://goo.gl/oPyic7

18 Rose, p. 146.

19 Stephen Walt, “The Enduring Relevance of the Realist Tradition,” in: Ira Katznelson & Helen Milner (eds.), Political Science: State of the Discipline III (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2002) p. 211.

20 Rose, p. 153.

21 Robert Keohane, Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions, and Political Change (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993).

22 Arthur A. Stein, Neoliberal Institutionalism in the Oxford Handbook on International Relations, Christian Reus-Smit & Duncan Snidal (eds.), (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 201–221.

23 K. J. Holsti, Taming the Sovereigns: Institutional Change in International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

24 This is the essence of Kant’s perspective in his famous Perpetual Peace.

25 Adler E. “Constructivism and International Relations,” in: W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse & B. A. Simmmons (eds.), Handbook of International Relations (London: Sage, 2002), pp. 95-118.

26 Matthew J. Hoffmann, “Norms and Social Constructivism in International Relations,” in: Robert A. Denemark (ed.), The International Studies Encyclopedia (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2010), p. 2.

27 Ibid.

28 B. Cronin, Cooperation under Anarchy: Transnational Identity and the Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), p. 18.

29 Jerel A. Rosati, “A Cognitive Approach to the Study of Foreign Policy,” in: Laura Neack et al., Foreign Policy Analysis: Continuity and Change in its Second Generation (Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice Hall, c1995), pp. 52-54.

30 Margaret G. Hermann, “Assessing Leadership Style: A Trait Analysis,” Social Science Automation (November 1999), accessed on 2/10/2017, at: https://goo.gl/PB2MwJ

31 Andrew Moravcsik, “The New Liberalism,” in: Christain Reus-Smit & Duncan Snidal, The Oxford Handbook of International Relations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 234-254.

32 M. Hollis & S. Smith, Explaining and Understanding International Relations (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), p. 74.

33 P. Zelikow & Condoleezza Rice, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft with A New Preface (Harvard University Press, 1997).

34 Andrew F. Cooper & Bessma Momani, “Qatar and Expanded Contours of Small State Diplomacy,” The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 46, no. 3 (2011), p. 114.

35 Turan Kayaoglu, “Thinking Islam in Foreign Policy: The Case of Qatar,” paper presented at the annual Convention International Studies Association (ISA), California: San Francisco, April 3-6, 2006, p. 2.