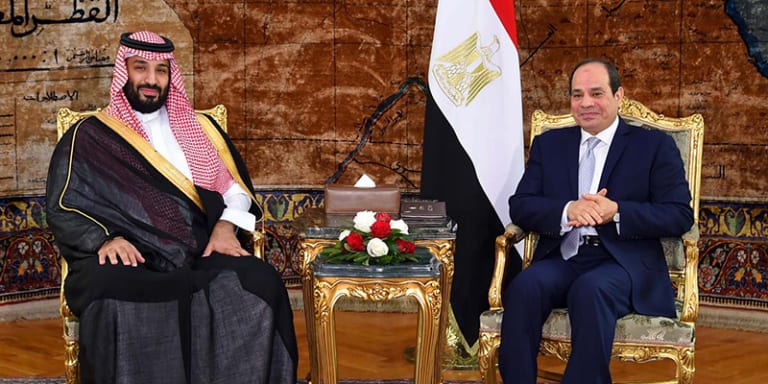

Egypt and Saudi Arabia continue to be strategic partners in the Middle East, buoyed by shared interests and certain threat perceptions. Saudi Arabia values Egypt’s large military force, which helps to protect a strategic body of water of common interest: the Red Sea. For its part, Egypt sees Saudi Arabia as its most important economic benefactor and as a workplace for Egyptian labor. The two also share a resistance to political liberalization and meddling in their internal affairs, which they fear the Biden Administration might do as part of a renewed American push to further human rights. This effort was in abeyance during the Trump presidency.

However, below the surface of this partnership there are jealousies and sometimes divergent political interests. Egyptians resent being the poorer partner to Saudi Arabia and their dependent relationship often requires them to withhold criticism. Riyadh views Cairo as still having pretensions to Arab leadership even though, in recent decades, power in the region has shifted to the Gulf states. In the political realm, while Saudi Arabia has joined Egypt and the United Arab Emirates in opposing the Muslim Brotherhood, the extent of Riyadh’s antagonism toward this organization is not as strong as that of its partners, particularly in the regional context.

Shared Regional Interests after the Arab Spring

In the aftermath of the 2013 military coup in Egypt, which overthrew the government of President Mohamed Morsi who was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait showered Egypt with about $12 billion in economic assistance, with total estimates of $30 billion through 2016. This largesse was not only meant to support what these countries hoped would be a return to the status quo ante—in other words, the restoration of a military-backed authoritarian regime that would oppose the democratic contagion arising from the Arab Spring—but also a shared ideological front against the Muslim Brotherhood.

Although for many decades Saudi Arabia had given refuge to Muslim Brotherhood activists and members, especially those fleeing Nasser’s Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s, it had a change of heart toward the organization by 2012.

Although for many decades Saudi Arabia had given refuge to Muslim Brotherhood activists and members, especially those fleeing Nasser’s Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s, it had a change of heart toward the organization by 2012. Like the Egyptian government after the 2013 coup, Riyadh designated the Brotherhood a “terrorist organization” in 2014, coming to see it as a threat to the stability of the Saudi kingdom.

Within the regional context, this opposition to the Brotherhood and its affiliated groups became a fault line whereby the area was divided into two opposing camps. On one side was Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia supporting anti-Brotherhood factions, while on the other side was Qatar and Turkey doing the opposite. This divide was most clearly manifested in Libya, with the Egyptian, Emirati, and Saudi group supporting the Libyan National Army (LNA) under self-declared Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar, who backed the secular House of Representatives based in Tobruk, while the Turks and Qataris supported the Tripoli-based, United Nations-supported Government of National Accord (GNA) of Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj, who was in an alliance with the Libyan equivalent of the Muslim Brotherhood. Egypt and the UAE provided military support to Haftar in his campaign against the GNA while Saudi Arabia gave him financial aid. The Turkish military intervention along with financial support from Qatar, however, helped to stem and then roll back Haftar’s offensive in 2020 against Tripoli. Although the Libyan warring parties have now entered into a cease-fire arrangement and have negotiated an interim government with elections slated for late 2021, it remains to be seen whether the outside parties will now desist from offering assistance. The warring factions and their external supporters are pledging to respect this new agreement, largely because neither Libyan faction is strong enough to take over the entire country. Nevertheless, the ideological cleavages remain.

In some respects, the Libyan proxy war was an outgrowth of the 2017 boycott of Qatar that was led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE and supported by Bahrain and Egypt. Part of their ire against Qatar was over Doha’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood and its hosting of prominent Brotherhood activists and media personalities. Egypt joined this boycott—even though about 300,000 of its citizens were working in Qatar—largely because of shared opposition to the Brotherhood and because of its desire to stay in the good graces of its main financial benefactors, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Cairo was lukewarm at best to the anti-Iran complaints these Gulf states had against Qatar, which maintained friendly ties to Tehran largely for economic reasons.

However, Cairo was lukewarm at best to the anti-Iran complaints these Gulf states leveled against Qatar which maintained friendly ties to Tehran, largely for economic reasons. Egypt did not and does not see Iran in such alarming terms as Saudi Arabia, for example, because Iran is not in its immediate neighborhood. In addition, Egypt does not have a Shia Muslim constituency like some Gulf states, some of whose leaders portray these Shia communities as a pro-Iran fifth column. Hence, in the other fault line in the region—the Sunni-Shia divide—Egypt and Saudi Arabia are not on the same page.

Some Divergence over the Yemen Conflict

This difference became apparent over the Yemen war, a conflict that, unlike the Qatar boycott, has still not ended. Although in March 2015 Egypt joined the Saudi-led coalition of Sunni states opposing the Houthi rebels, who follow the Zaydi branch of Shia Islam and have received some Iranian assistance, Cairo was very reluctant to engage in this conflict militarily. Much of this reticence came from unhappy memories of its military intervention in Yemen in the 1960s, which bogged down the Egyptian army for five years and led to many Egyptian casualties. Another concern was Cairo’s uneasiness about getting involved in what was seen as a sectarian war. The most Egypt did militarily was to deploy naval vesselsoff the Yemeni coast and shell some Houthi columns for a short period in the initial stages of the conflict. Politically, Cairo has backed the Saudi-supported government of Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi in order to stay in Saudi Arabia’s good graces. Its only real concern, however, is to make sure that shipping through the Bab al-Mandab Strait—which connects the Arabian Sea to the Red Sea—is unencumbered: a slowdown of maritime traffic would adversely affect Suez Canal tolls, which amount to about $5.8 billion a year and represent one of Egypt’s main sources of foreign exchange earnings.

In reaction to this threat (as well as to Houthi attacks on Saudi shipping), Egypt has beefed up its naval presence in the Red Sea, and has hosted both naval and land exercises with its partners. In July 2019, for example, it carried out joint naval maneuvers with the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, and in November 2020, it hosted major military training exercises with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, Bahrain, and Sudan, held at the Muhammad Naguib military base in northwestern Egypt. The Egyptian strategic expert, Major General Samir Farag, stated that the exercises would act as a “deterrent message” to those who sought to harm Egyptian and broader Arab national security. Would Egypt actually deploy forces to Saudi Arabia in the event of an Iranian attack in the Gulf? Regardless of the answer, these exercises also serve as a political statement of Egyptian support for Saudi security.

Cairo’s Focus on the Eastern Mediterranean Rather Than Iran

From Cairo’s perspective, however, its most immediate threat today is Turkey, not Iran. Under the presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey has not only given refuge to many Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood activists and allowed their media outlets to broadcast anti-regime messages into Egypt, but it has also tried to encroach upon Egypt’s Mediterranean Sea boundaries where significant gas deposits have been found. This is why Egypt is also ramping up naval maneuvers with its partners in the eastern Mediterranean.

Although Saudi Arabia has joined Egypt in opposition to Turkey in recent years and has even encouraged its private sector to boycott Turkish goods, there appears to be a softening by Riyadh toward Ankara.

Although Saudi Arabia has joined Egypt in opposition to Turkey in recent years and has even encouraged its private sector to boycott Turkish goods, there appears to be a softening by Riyadh toward Ankara. In November 2020, Erdoğan and Saudi King Salman held a phone conversation and promised to keep “channels of dialogue open.” After the end of the boycott against Qatar, Doha—which has close ties to Turkey and hosts a Turkish military base—offered to mediate between Ankara and Riyadh. Some analysts have suggested that this possible rapprochement came because Saudi Arabia, believing that the US security umbrella will not be as strong under President Joe Biden as it was under former President Donald Trump, may be looking for alternative security partners. This easing of tensions between Saudi Arabia and Turkey may continue or slow down; still, such moves are making Cairo nervous.

The Egyptian government under Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi is undoubtedly worried that Saudi opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood, perhaps not at home but in the region, may be wavering. In the Yemen conflict, Saudi support for the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Islah Party was one of the major points of contentionbetween Abu Dhabi and Riyadh. Although Cairo did not criticize Saudi Arabia over its ties to Islah, Egyptian officials most likely shared the UAE’s concerns. If Saudi Arabia were to indeed mend fences with Turkey, Egypt—as well as the UAE—would interpret this as a loss for their anti-Muslim Brotherhood campaign.

Extensive Economic Links amid Problems over Treatment of Workers

Cairo has been reluctant to criticize Riyadh for fear of hurting its important economic links to the kingdom. Egyptian exports to Saudi Arabia were approximately $1.7 billion in 2019, and Egyptian business leaders hoped to increase that number by replacing Turkish consumer goods with those from Egypt—another reason why Cairo is worried about a rapprochement between Riyadh and Ankara. In addition, Saudi investments in Egypt are worth about $54 billion, of which $44 billion are from Saudi companies either operating in Egypt on their own or in partnership with Egyptian private firms.

Perhaps more importantly, given Egypt’s high unemployment rate, is the roughly three million Egyptian workers in Saudi Arabia who include teachers, doctors, technocrats, as well as manual laborers. Although some of these workers have returned home as a result of the slowdown in the Saudi economy because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the remaining workers still contribute a large portion of the total Egyptian worker remittances from all countries (estimated at $30 billion in 2019). While the exact amount of Egyptian worker remittances from Saudi Arabia is unknown, it is estimated that 75 percent of total Egyptian remittances come from the Gulf states, with 39 percent from Saudi Arabia alone.

However, there have been reports of ill-treatment and assaults on Egyptian workers in the kingdom which have the potential to become a political issue. On December 29, 2020, an Egyptian teacher was shot and killed by two of his Saudi students. Five months earlier, two Egyptian laborers were killed by a Saudi national over a dispute on construction work at his residence. Egyptian authorities have tried to downplay such murders, calling them “mere separate incidents that people carry out, and do not rise to the level of a systematic phenomenon against Egyptian workers in Saudi Arabia.” However, human rights activists have called on the Sisi government to do more to protect Egyptian workers and to compel Saudi authorities to punish the perpetrators. Sisi undoubtedly hopes that protests, which broke out in 2017 when he decided to hand over two islands near the Strait of Tiran to Saudi Arabia after being under Egyptian control since 1950, not be repeated over these workers’ ill treatment and deaths. To contain the potential for protests, he may order Egyptian diplomats in the kingdom to raise this issue with Saudi officials quietly.

Implications for US Policy

There has been much speculation that the Biden Administration will not treat Saudi Arabia and Egypt with kid gloves, as was the case during the Trump presidency. During the presidential campaign, Biden and his foreign policy team criticized Egypt and Saudi Arabia for human rights abuses, and Biden recently announced he would end US military offensive support for the Saudi campaign in the Yemen war because of the high number of civilian casualties. Hence, opposition to a renewed US push on human rights may be another shared interest between Cairo and Riyadh.

But instead of resisting US pressure on the human rights front, Egypt and Saudi Arabia would be well advised to rethink their approach to restricting political space in their countries, which is clearly not a smart strategy in the long term. US policy-makers can reassure these countries that they will still be seen as US strategic partners even while there is more scrutiny of how they treat their own citizens. Such diplomacy will not be easy to carry out given these countries’ national sensibilities; but to ignore human rights problems, as was the case with Trump, is not a winning strategy for the United State either.