Noura Erakat’s book, Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, arrives at a poignant juncture as Palestinians commemorate the 71st anniversary of the Nakba, the catastrophe that began their dispossession in 1948. It also comes at a time of major developments in the century-old Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The Trump Administration is promising the world a “deal of the century” supposedly to end the conflict. Israel’s right-wing parties triumphally, but illusorily, are writing what they think is their final episode of the conquest of Palestine and the liquidation of the Palestinian cause. For their part, the Arab countries, to different extents and based on disparate agendas, are gradually abandoning the important cause that has defined their modern history. Yet the book reminds all that any resolution to the conflict must be based on realizing the national aspirations of the Palestinian people, who remain attached to their land and continue to be the strongest and most legitimate defenders of their own rights.

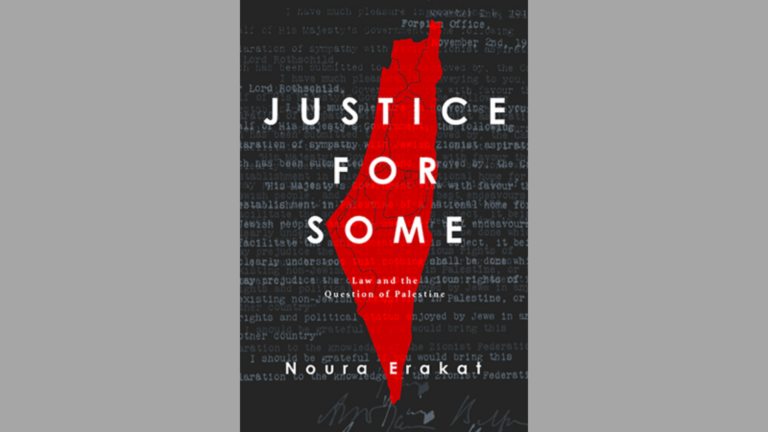

Indeed, Erakat’s book explores the questionable legal underpinnings of Israel’s subjugation of close to six million Palestinians inside its pre-1967 borders and in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip.* Hers is a needed denunciation of what passes for historical, political, ideological, and other analyses that ignore Israel’s making the conflict intractable and enable a colonization project that eradicates the Palestinians’ identity, culture, and rights. Justice for Some is in fact an antidote to the current and, so far, dominant atmosphere in the United States that sees Israel as a destiny realized and its practices legal and legitimate.

Erakat provides an expansive yet succinct analysis of the history and development of the question of Palestine since the early decades of the 20th century after Lord Balfour pledged the British government’s support for the establishment of a Jewish national home in the former Ottoman territory. She goes through the history of the Palestinian dilemma and Israel’s supposed triumph to explain how the State of Israel has been able to transform itself from a near-impossibility to a settler-colonial entity that now occupies, controls, and governs the entire expanse from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. To Erakat, none of this was inevitable; indeed, it was possible and was achieved through brutal force but also, and essentially, by an activist program of what she calls “legal work.” This was undertaken by powerful actors––such as Israel––to reinterpret international law and create a justification for previously unjustifiable conditions in Palestine—what would, in current American parlance, be a “spinning” of facts.

To be sure, Erakat’s main argument is that law is not enough to establish justice because, like everything else, it operates in a political world that values power and the ability to cajole the unconvinced, justify illegal developments, twist facts, and force unwanted, and unwarranted, results on the powerless. She writes that “…law is politics: its meaning and application are contingent on the strategy that legal actors deploy as well as on the historical context in which that strategy is deployed” (p. 4). To Erakat––and arguably to every justice-seeking actor––this is worrisome since the applicability of laws must be subject to geopolitical realities that may not favor the less powerful actors. In the Palestinian-Israeli case, law as used and applied during the British mandate of Palestine, after the establishment of Israel in 1948, and throughout the period of Israel’s expansion as a settler-colonial polity has been manipulated to dispossess the Palestinians and deny them their legitimate national rights.

The author devotes extensive discussion and analysis to what can be called an “original sin”: the British promise in 1917 to give Palestine to the Jews to establish a national home, over the strong objection of the Palestinians who made up 90 percent of the population. Once the British government endorsed Lord Balfour’s pledge, his declaration by default became one of the British empire’s legal provisions and later part of international law when the League of Nations codified the British Mandate for Palestine. Subsequently, any Palestinian opposition to the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine and struggle against it became illegal according to international law. In essence, the Palestinians—due to no fault of their own and despite their strong objections—found themselves on the wrong side of the law that was wholly promulgated by western nations.

The manipulation of law––accomplished through adroit “legal work” by Israeli lawyers and implemented by dedicated civil servants, government officials, local administrators, and the like––became the norm after Israel’s establishment. Palestinians who fled Israel during the 1947-1948 hostilities and war were prevented from returning to Palestine while the Israeli government practically emptied areas to make room for large influxes of Jewish refugees. Only an estimated 160,000 of a total 750,000 Palestinians remained while the rest were made refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Laws such as the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law, the 1950 Law of Return, and the 1952 Nationality Law both deprived the expellees from their ownership of land and ensured the supremacy of the Jews in the new state. Martial law was declared and operated until 1966 to help build the essence of the Israeli state, and it was clearly intended to exclude the original Palestinian inhabitants. In other words, the malleability of the law served the whims of the victor as the weak and dispossessed looked on with despair.

Similarly, manipulating international law, such as that on occupation, continued full force after the conquests of 1967. Erakat argues that 1967 witnessed the beginning of an Israeli legal theory that considered the newly occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem and Gaza Strip sui generis territories—that is, having a unique status. To Israeli government legal scholars, the occupied territories had an ambiguous legal status because they had no sovereign. The West Bank and East Jerusalem were annexed by Jordan after 1948, but only Britain and Pakistan recognized that annexation. The Gaza Strip was administered by Egypt. Neither area had been a state before or belonged to a legal sovereign entity; as such, Israel’s legal experts treated them as unique places where international occupation law did not apply. Thus it was acceptable to allow their settlement by Israeli civilians, slowly in the beginning but quickly and precipitously after right-wingers took over the reigns of government in 1977. Today, Israeli settlers number more than 600,000 in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Israel also worked on finding new interpretations of international law regarding the treatment of Palestinians under occupation, the annexation of East Jerusalem, the separation wall, “targeted killings” of terrorism suspects without due process, preemptive strikes and operations, and other practices that transpired principally from Israel’s status as the more powerful actor. Israel had, and still has, the means of control and the activism necessary to justify its behavior. Most importantly, however, it has the support of the most powerful international actor, the United States, which actually objected on many occasions to the manipulation of clear international laws—but still let Israel get away with it. To be sure, it is the American umbrella that has allowed the legal manipulation to stand and the new interpretations of laws to have their effect.

Erakat laments the current conditions of Palestinian leadership. She believes that the Palestine Liberation Organization before the 1990s whittled away opportunities to change the status of the Palestinians as the weak link in the conflict. Most decisively, she believes, was the PLO’s decision to sign off on the Oslo peace process in which it basically gave up whatever strength it had left when it decided to recognize Israel and end the armed struggle. She writes that “…without a resistance framework, Palestinians would not be able to recalibrate the balance of power to compel Israel to relinquish its control” (p. 164). By doing so, the PLO surrendered its ability to influence conditions to the dominant role of the Israeli-American powerhouse, all in exchange for a Palestinian Authority that remains toothless in comparison. The Palestinians still do not have an independent state; Israel continues to maintain full control over Palestinian lands; and the United States proved that it could not be the honest arbiter of the decades-old conflict.

The bleak picture that Erakat paints of the Palestinian condition vis-à-vis Israel’s dominance does not mean that she has given up on changing the status quo. Importantly, she sees that the pursuit of legal arguments in order to change difficult conditions is still possible—but after the necessary work to alter current geopolitics. She writes: “To achieve the law’s emancipatory potential, Palestinians must wield it in the sophisticated service of a political movement that targets the geopolitical structure that has rendered their claims exceptional and, therefore, non-justiciable” (p. 220). She also finds great hope in the work of Palestinian and international civil society organizations and dedicated human rights activists who, for example, are behind the success of the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement that has forced Israel to reckon with its behavior toward Palestinians. Erakat underlines the BDS movement’s aims that Israel “…first, ends its occupation of Arab lands; second, establishes meaningful equality for its Palestinian citizens; and third, fulfills the right of return of Palestinian refugees” (p. 228).

The book’s helpful introduction lays out Erakat’s argument about the political nature of law and prepares the reader for the coming analysis. Chapter 1 is a poignant discussion of what the author calls “colonial erasures” of Palestinians’ identity and national rights, from the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to the emergency law that ended in 1966. Chapter 2 is devoted to the “permanent occupation” of all Palestinian lands and the legal justifications for maintaining it since 1967. In Chapter 3, Erakat discusses the development of the Palestinian revolutionary response to Israel’s policies and the pragmatism the PLO showed in garnering international support to promote Palestinian rights. Chapter 4 is dedicated to a discussion of the start and end of the Oslo peace process that, in effect, has rendered the Palestinian Authority (PA) powerless to change conditions.

In Chapter 5, Erakat delves into the post-PLO return to the occupied West Bank and the policies Israel has pursued to manipulate its relationship with the PA. The chapter also offers a detailed explanation of the Israeli legal doctrine that arrived at justifications for the illegal siege of the Gaza Strip, preemptive strikes and operations, targeted assassinations of Palestinian activists, and other policies. The Conclusion wraps things up and reminds readers that in 2018, Israel indeed became the settler-colonial entity it was always meant to be, controlling 100 percent of historic Palestine through brute force and an active program of “legal work” that reinterpreted international law to sustain the status quo. Regrettably, the book lacks a bibliography, but that is remedied by a very impressive 65-page list of endnotes for the informative chapters.

Justice for Some is a necessary addition to any library on the development of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the seminal dilemma that has plagued the Middle East for over a century. It also is a succinct analysis that can be used in law libraries to study how to prevent the use of the law in justifying injustice. It should be recommended reading for lawyers, political scientists and activists, government officials, international law practitioners, and anyone interested in the genesis, perpetuation, and legal rationales for Israel’s conquest of Palestine and the dispossession of its people.

* While Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, it is still considered an occupying power because it maintains effective control over the territory according to occupation law and international humanitarian law and international human rights law. Israel’s High Court of Justice has maintained that having no actual presence in the Strip does not negate Israel’s responsibility to maintain the safety and welfare of Gaza’s inhabitants. See “The Gaza Strip – Israel’s obligation under international law,” B’Tselem, January 1, 2017, at https://www.btselem.org/gaza_strip/israels_obligations. (Accessed May 10, 2019.)