Turkey’s military battle for control of Kurdish-majority Afrin in northern Syria is in its second week. The advance of Turkish forces has been methodical, although with civilian casualties, and has achieved tactical successes on the ground at the expense of the militia of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) that is closely aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). YPG fighters have withdrawn to the center of the city and have resorted to asymmetrical warfare tactics in order to slow the Turkish advance.

Not unlike other military incursions, the Turkish campaign––dubbed Operation Olive Branch–– seems to have exacted a high political and military toll on Turkey because it is more difficult and risky than previous military incursions into Syria, such as those to control the city of Jarablus as well as Operation Euphrates Shield. In the latter, Turkey cleared the city of al-Bab from fighters for the so-called Islamic State (IS), with the assistance of the US-led international coalition from the air and the Free Syrian Army on the ground. In the current operation, the United States has maintained what can clearly be called passive neutrality as Trump Administration officials relayed their behind-the-scenes reservations and urged the Turkish government to ease its assault and concentrate on fighting IS.

The Turkish government appears to consider the operation a serious and final decision to militarily end the presence of YPG fighters on the Turkish-Syrian border, whatever the political cost. Ankara also seems to have lost all confidence in American promises and harbors many suspicions about American credibility and plans for Syria in the foreseeable future. As such, Turkey has finally ended its three-year hesitation to eradicate the YPG from the border area, a period in which it received American assurances that the United States would call back the weapons it supplied the Kurds in their fight against IS. Washington also reneged on promises to share detailed intelligence about weapons deliveries. Today, with levels of mutual confidence at their lowest, the American-Turkish relationship is subject to increased tension as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoǧan demands the withdrawal of American troops in Manbij, to the east, which appears to be the next target after Afrin.

The Russian and American Positions on Afrin

Russia’s position on Operation Olive Branch is of utmost significance at present. Russia controls the Syrian regime’s political and military decision-making and has simultaneously supported and financed the YPG—and indeed allowed them to open an office in Moscow in 2016. It has also invested heavily in trying to impose a peaceful resolution for the Syrian crisis, while ensuring Bashar al-Assad’s fate, and has campaigned hard against the armed Syrian opposition to force it to accept its conditions.

Turkey thus knew from the beginning that Russia’s agreement for its Afrin operation was essential for its success. While it assisted in previous talks in Astana, Kazakhstan, which produced agreements on the establishment of de-escalation zones, it now is pushing the Syrian opposition to participate in the Sochi conference. Russia’s response to the Turkish gestures was to pull Russian security units from areas around Afrin and to allow for the entry of Turkish forces. It also accepted the Turkish government’s discourse on the YPG and criticized the United States’ stance regarding the Kurds in Syria.

On the other hand, the United States reasons that Afrin holds no strategic value; there are no US forces there since the Islamic State existed and operated in Manbij and in areas east of the Euphrates River. In fact, Afrin fell to the YPG in 2012 and was never threatened by IS, which allowed the city to have its own local government and to join two other Kurdish cantons controlled by the militia, in addition to Kobane (Ayn al-Arab), Qamishli, Manbij, and now Raqqa.

In essence, Turkey has gained Russia’s acceptance because of strategic calculations and American agreement by default. While these developments change the nature of the conflict in northern Syria, they also reflect fundamental changes in the overall conflict—from one primarily between superpowers to one between regional states. Every city that has experienced war is now exposed to the calculations of both international and regional actors, which will unfortunately make the Syrian conflict an endless and pointless struggle where different interests will lead to more conflagrations. This was obvious in the border city of Azaz whose control has switched between myriad parties: the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in 2011, al-Qaeda (Jabhat al-Nusra, now Tahrir al-Sham) from 2013 to 2015, IS for six months in 2013, the YPG from 2015 to 2016, and finally Turkish forces that occupied it from the YPG in 2016. In 2016, the Islamic State attempted to occupy Azaz but Turkish and FSA troops held on to it, placing it under the authority of the provisional Syrian government that is controlled by the opposition and has its offices in the Turkish border city of Gaziantep.

The Future of the Free Syrian Army

Since its establishment in 2011 by defecting officers from the Syrian Army, the FSA has failed to maintain a firm structure or assert its institutional esprit de corps. Personal differences and infighting among its leaders, and interference by regional powers supporting and funding its operations, doomed its mission. On the other hand, the Russian intervention in September 2015 specifically targeted its units since they represented the moderate factions in the opposition.

Moreover, the FSA lacks a unified and centralized command structure and has no discipline or respect for rank. Today it has become what can be called fighting groups that are mostly interested in defending specific areas or cities from organized attacks by government forces. What has also affected the FSA’s morale was its inability to defend against brutal attacks by the Syrian Army, which has used weapons of mass destruction, barrel bombs, and sieges against such cities as Daraya, Aleppo, Eastern Ghouta next to Damascus, and many areas of the countryside.

The political opposition is also to blame for the failure to unify an opposition force that believes in transition from authoritarian rule. The same obtains with regional powers and influences. By 2014, the Islamic State began to attack areas under the FSA’s control to end its presence in both the north and south of the Syrian hinterland. By 2016, the impact of fighting IS, coupled with the Russian assault on the FSA, dissipated the group and indeed forced the disappearance of many of its formations, like the Tawhid Brigade and the Union of Syria’s Revolutionaries. These and others had received American support, although not sufficiently, before the United States finally ended all support to the FSA last November.

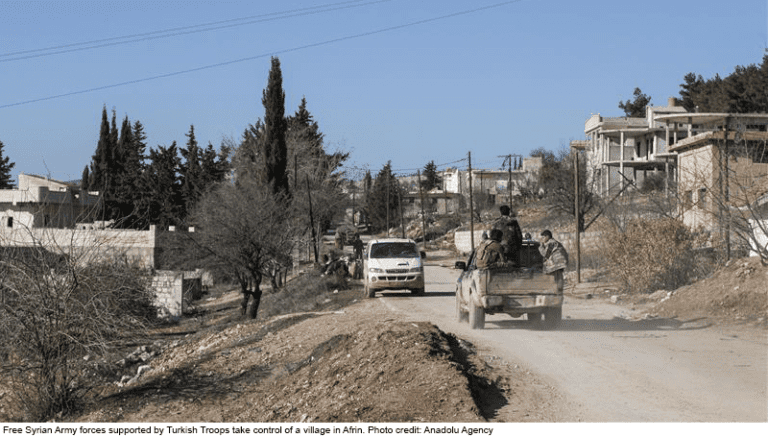

Today, it appears that Turkey is most interested in rehabilitating the different groups that once formed the FSA and has relied on them in Operation Olive Branch. It actually gathered forces that previously formed the Sham Brigade and the Nour al-Din al-Zinki Movement and gave them a larger role and say in the current operation. This has become clear from the high number of casualties that the FSA has sustained in the Afrin campaign, where the army played a pivotal role in taking such strategic areas as Jinderis to the southwest, Qastal Jandour, and Birsaya Mountain to the west of Azaz. It also received aerial support from the Turkish air force and from rocket launchers deployed around Afrin.

On the other hand, the humanitarian cost of the operation is likely to increase because of the large number of civilians from Aleppo and Idlib, since 2011, who settled in Afrin seeking the relative peace and safety that the YPG was able to ensure. This is why many fear that the post-Afrin period may witness the expulsion of refugees as the Kurdish-majority city may turn on the non-Kurdish inhabitants.

It is possible, however, that the participation of the Free Syrian Army in the Afrin operation may help restructure the FSA to become a stabilization or peacekeeping force in the areas still controlled by the opposition. But this will require a clear plan from the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, which should insist on making the FSA a party to any peace plan in the post-IS period in northern Syria. This, in turn, will require much effort and assistance from regional and international actors, who should decide to accept the Free Syrian Army as a legitimate force in the areas outside the control of the Syrian government.