The relationship between religion and the state is controversial and problematic in the Arab world, particularly with the absence of clear demarcations that could define it. Historically, attempts by the state and various political forces to employ religion in the political arena have caused many problems. While the main role of religious institutions should revolve around fulfilling peoples’ religious and spiritual needs, it may sometimes expand to affect the political and social aspects of their lives as well.

In Egypt, for example, institutions such as Al-Azhar and Dar Al-Ifta are not merely religious or spiritual entities but also have an impact on political life. Thus, the relationship between these institutions and the state has always been a subject of conflicts, tensions, and troubles. In addition, the state constantly attempts to maintain control over these institutions in order to legitimize its policies and to deprive its political adversaries, particularly Islamists, from using religion in the political arena.

Al-Azhar: The Dilemma of Autonomy

Al-Azhar Mosque is one of the oldest religious institutions in the Islamic world. It was established over a thousand years ago by the Fatimids who entered Egypt in 969 AD. Al-Azhar is not only an ordinary mosque for conducting Islamic prayers and rituals but also serves as a university for students from all over the Muslim world who seek to study Islam. Its weight and influence transcend Egypt and reach countries in the entire Arab and Muslim worlds. Historically, Al-Azhar has enjoyed a notable degree of autonomy from the state. Its financial resources come from various endowments, enabling it not to rely on the state for its budget and expenses. The position of the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar was created during the Ottoman era with the proviso that he would be chosen freely from among the highly respected and well-educated scholars (the ulama) without state interference. This empowered and granted the Grand Imam considerable independence from state power.

The importance of the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar is not only due to his religious and spiritual status and weight among Muslims, but it is also related to his indirect political influence as a link between the state and the people.

The importance of the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar is not only due to his religious and spiritual status and weight among Muslims, but it is also related to his indirect political influence as a link between the state and the people. Throughout history, he was a member of the ruler’s court in Cairo, whose sessions used to be held every week under the leadership of the governor to discuss the political, economic, and administrative issues in Egypt. In addition, Al-Azhar was one of the most important institutions in Egypt after the defeat of the Mamluks in the late 18th century; at that time, the sheikhs and leaders of Al-Azhar led the resistance against French occupation and played a pivotal role in grooming Muhammad Ali to become Egypt’s ruler in the early 19th century. Ironically, it was Muhammad Ali who later regulated and limited the powers of Al-Azhar.

Since the emergence of the so-called “modern state” in Egypt, the independence and autonomy of Al-Azhar has declined. For example, the selection of the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar became a prerogative of executive power instead of a result of elections by the ulama. This subordinated Al-Azhar to the state. The institution’s position eroded during the 1950s and 1960s as the state took full control of Al-Azhar. Former President Gamal Abdel-Nasser issued a decree in 1961 to restructure and reorganize Al-Azhar, one that placed several limitations on its power and independence. For example, this decree ended the role of the Council of Senior Scholars who used to select the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, reduced the powers of the Grand Imam to manage his affairs, and transferred some powers to the Minister of Endowments. These changes created tensions and problems between Al-Azhar and the state.

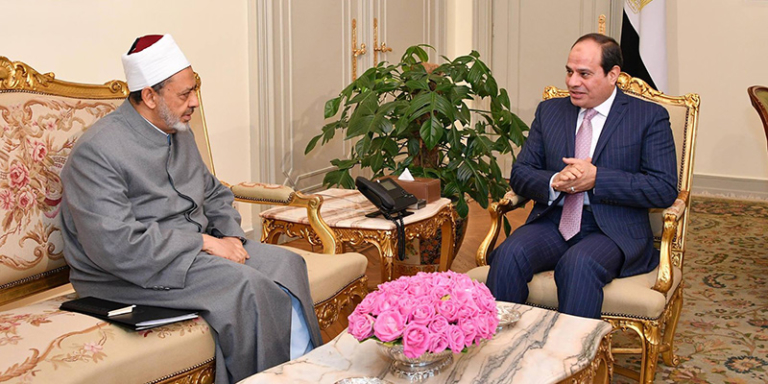

It was not until the January uprising of 2011 when Al-Azhar regained some of its independence. Later, in January 2012, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which at that time was the caretaker of Egypt after the downfall of former President Hosni Mubarak, amended the Al-Azhar Law of 1961 in order to give more autonomy to the institution. According to these amendments, the Grand Imam would be elected by the Council of Senior Scholars, which is composed of 40 members, through a secret ballot in a closed session attended by at least two-thirds of the members. In addition, the Grand Imam would remain in his position for life and the president would not have the power to dismiss him. These changes strengthened the autonomy of Al-Azhar and empowered the Grand Imam vis-à-vis the state. In fact, this is one of the reasons for the ongoing tensions between the current Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Sheikh Ahmad Al-Tayyeb, and President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi. Although Al-Tayyeb sided with Sisi during the coup of July 3, 2013, which toppled former President Mohamed Morsi, he rejected Sisi’s policies afterward. For example, Al-Tayyeb vehemently condemned the killing of protesters after the coup and the following August’s bloody dispersal of the Rabaa al-Adawiya sit-in, during which the army and security forces killed over 800 peaceful demonstrators on August 14, 2013. He also disagreed with Sisi’s religious views which are considered as contradicting Islamic teachings and traditions.

Dar Al-Ifta under the Authoritarian Thumb

After Al-Azhar, Dar Al-Ifta is the second most important religious institution in Egypt and was established in 1895 to reorganize and regulate the religious sphere in modern Egypt. Specifically, the state sought to control the process and procedures of issuing fatwas (religious rulings) and to preclude non-specialists and unauthorized individuals from doing so. Since its establishment, Dar Al-Ifta has been attached to the Ministry of Justice and the Grand Mufti decrees non-binding fatwas on death sentences issued by civil courts—a task that has remained a subject of controversy to this day. The Grand Mufti was also entrusted with determining the timing of the new crescent moon of each month of the lunar year and announcing its beginning, especially during Ramadan, and ascertaining the beginning and end of fasting during the holy month. It should be noted that in 2007, Dar Al-Ifta became a separate entity and is no longer part of the Ministry of Justice.

As is the case with Al-Azhar, the relationship between the state and Dar Al-Ifta has witnessed a tug of war. Some muftis tried to gain independence from the state, especially during the first half of the 20thcentury; however, the state remained in control of Dar Al-Ifta and managed its affairs during the last half century. Moreover, in some cases the state attempted to use Dar Al-Ifta in its struggle with Al-Azhar, especially during the post-2013 coup era. For example, the Sisi regime tried to put forward a bill to regulate Dar Al-Ifta, one that aimed to create a parallel entity to Al-Azhar and marginalize the latter’s role. This was rejected by the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, who viewed it as an attempt to reduce the powers of the Al-Azhar institution, which would be considered unconstitutional. In fact, since Sisi became president in 2014, Dar Al-Ifta has turned into a mouthpiece of the state and has been employed as a political pawn to legitimize Sisi’s internal and external policies.

Since Sisi became president in 2014, Dar Al-Ifta has turned into a mouthpiece of the state and has been employed as a political pawn to legitimize Sisi’s internal and external policies.

The institution has gone out of its way to show unbridled support for Sisi and his regime. Dar Al-Ifta’s former Grand Mufti, Sheikh Ali Gomaa, as well as his successor, Sheikh Shawqi Allam, have voiced their advocacy of Sisi’s policies against the Muslim Brotherhood, which the Egyptian president considers to be his main political threat. In 2020, Allam approved of the regime’s campaign against the organization and attacked it as a nightmare for Muslims and the world. Similarly, Gomaa criticized the Brotherhood harshly and justified its suppression by the military. He and other religious scholars were recorded by the Egyptian military exhorting troops to do what was required of them to quell what they claimed was sedition. The videos were shown to troops who may have had misgivings about the 2013 massacre of pro-Morsi protesters in Cairo’s Rabaa Square.

A Religious Guardianship?

Article 7 of Egypt’s constitution of 2014 states that “Al-Azhar is an independent scientific Islamic institution, with exclusive competence over its own affairs. It is the main authority for religious sciences, and Islamic affairs. It is responsible for preaching Islam and disseminating the religious sciences and the Arabic language in Egypt and the world. The state shall provide enough financial allocations to achieve its purposes. Al-Azhar’s Grand Sheikh is independent and cannot be dismissed. The method of appointing the Grand Sheikh from among the members of the Council of Senior Scholars is to be determined by law.” This article raises many questions not only regarding the relationship between the state and Al-Azhar but also in relation to the institution’s religious, social, and cultural impact on Egyptian society. Some activists and human rights advocates criticize this article and consider it anti-democratic. They believe it imposes a sort of religious guardianship on society that affects the freedoms of expression and belief. According to Amr Ezzat, who runs the “Freedom of Religion and Belief” program at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Freedoms, religious institutions such as Al-Azhar and Dar Al-Ifta impose their authority on everyone in Egypt at the expense of freedom of belief and expression which leads to discrimination.

Between Rebellion and Domestication

Although the Sisi regime claims that it came to power in order to prevent the abuse of religion by Islamists, it relies heavily on religion to advance its political agenda and legitimize its policies. Over the past few years, Dar Al-Ifta has promulgated dozens of fatwas and religious statements to support the regime’s position on Libya, attacking Islamists, and harshly criticizing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. It issued several proclamations in support of the Egyptian government’s policies in combatting the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite its autonomy, Al-Azhar still relies on the state in terms of financial resources and management of its affairs. For example, the state has control over mosques, appoints and monitors their imams, and pays their salaries.

Despite its autonomy, Al-Azhar still relies on the state in terms of financial resources and management of its affairs. For example, the state has control over mosques, appoints and monitors their imams, and pays their salaries. By law, penalties for preaching or giving religious lessons without a license are imposed by the Ministry of Endowments or Al-Azhar and include imprisonment for up to one year or a fine of up to 50,000 Egyptian pounds. The penalty is doubled for repeat offenders. The Ministry of Endowments’ inspectors also have the judicial authority to arrest imams who violate the law.

It is important to note that not all religious institutions provide political support to the regime. There are four entities currently authorized to issue fatwas: the Council of Senior Scholars of Al-Azhar, the Al-Azhar Center for Islamic Studies, Dar Al-Ifta, and the Fatwa Department in the Ministry of Endowments. As mentioned earlier, Al-Azhar rejected some of the regime’s policies, which led to tensions between Sisi and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar. Likewise, the support provided by some of these institutions to the current regime does not stem from their agreement with its policies, but sometimes because of their fear of Islamists, especially the Muslim Brotherhood. There is a historical hostility between these institutions and the Brotherhood and the Salafis, which was clear during 2012-2013, the period when the Brotherhood ruled Egypt.

As things stand today, Egypt’s religious institutions do not appear to be able to make themselves truly independent from political authority, especially that of the Sisi regime. Since the coup of 2013, Sisi’s successive governments have been keen to maintain the allegiance of the country’s religious institutions through both cajoling and outright pressure. This is unlikely to change any time soon. The hope is that said change will take place when authoritarian rule itself can no longer maintain its control over Egyptian society.