This paper is part of ACW’s fourth book, titled The Arab World Beyond Conflict.

Sectarianism and sectarian conflict in the Middle East are often presented as centuries-old religious and theological phenomena. Those who subscribe to such thinking believe sectarianism runs so deep that it cannot be addressed or resolved. This view is widespread in the media, policy circles, and in some academic quarters as well. People high in the echelons of power, such as former President Barack Obama, have also embraced this view. In fact, in his 2016 State of the Union address, Obama said, “The Middle East is going through a transformation that will play out for a generation, rooted in conflicts that date back millennia”.i

In reality, however, Sunni-Shia sectarian conflict is a modern revisionist phenomenon that largely constitutes a reaction to specific modern-day events and socioeconomic problems. Its roots can be traced back to the 1979 Iranian revolution rather than seventh-century religious and political divisions within Islam. It has been exacerbated by a set of subsequent external and domestic events; chief among them is the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the 2011 Syrian revolution, the war in Yemen, and other running conflicts in the region. In fact, sectarianism signifies the failure of state building in the Middle East, which points, in turn, to foreign intervention.

Roots of Modern Sectarianism

The 1979 Iranian revolution brought to power the first religiously oriented regime in the modern history of the Middle East. Before the Islamic revolution in Iran, secular regimes reigned across the region, including in Iran itself. Although present in public life, religion had not been a key factor in Middle Eastern politics before 1979. Indeed, Bernard Lewis drew attention to the rise of Islam a few years before as a result of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.ii Although that war did indeed contribute to the rise of Islamism as a result of the failure and collapse of pan-Arabism, movements that advanced political Islam were not close to gaining power anywhere in the Middle East before the Iranian revolution. Iran did not only bring to power turbaned mullahs in a pivotal Middle Eastern power but also stirred sectarian tension across the region. Shia Iran’s endeavors to export its revolution to neighboring Sunni Arab countries led to a backlash: Iraq decided to act preemptively, declaring war on Iran in 1980.

As part of its revolutionary rhetoric, Iran also called on Shia communities in the Arab Gulf states to rise against their own rulers. Sunni Arab Gulf states hence supported Iraq in the eight-year war against Iran, pouring billions of dollars into Iraq’s economy. Before the Iranian revolution, Sunni-ruled Iraq was seen by the smaller and weaker Arab Gulf states as the major security threat. Its radical, pro-Soviet policies and its support for leftist and Marxist groups in the Gulf were matters of concern for the GCC countries.iii Iran interpreted the Gulf states’ support for Iraq as an act of hostility, unleashing a series of destabilizing activities against them, particularly Kuwait. To counteract Iran’s threat, Arab Gulf leaders met in Riyadh in May 1981 and announced the establishment of the GCC. Iran viewed the bloc as an antagonistic Sunni club.

Contained and humbled by the failure to export its revolution or win over Shia communities in the Sunni-majority Arab Gulf states, Iran turned inward. The 2003 US invasion of Iraq, which removed a key bastion against Iranian expansionism, opened a new window for Tehran to resume its efforts to establish a Shia crescent, stretching through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon on the shores of the Mediterranean.iv

The Shia revival, and the surge in sectarian politics in Iraq and later in Syria within the context of the Arab Spring, caused grave concern among the Sunni-majority Arab countries. It also led to the rise of the so-called Islamic State (IS) and other radical Sunni groups. IS presented itself as the champion of Sunni Islam against the rise of Shia power and Iran’s expansionist policies. To counteract IS and what it perceived as Sunni rebellions in Syria and in Iraq, Iran established Shia militias. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states supported Sunni groups and a war by proxy ensued between the two sides, with Syria serving as the main battleground. Shia and Sunni militias wreaked havoc across the region. They were the ultimate expression of the failure of state building in the Arab region.

State Failure

Armed non-state sectarian actors emerged as a reaction to a set of domestic and external conditions, all of which are related to the failure of state building in the Middle East. In particular, they also reflect the state’s inability to perform its key functions, such as warding off external threats, providing adequate public services, and protecting the civil rights of its citizens.

The dismantling of the Iraqi state coupled with the disbanding of the Iraqi army by the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq—and the failure to replace it with a state based on the rule of law and neutral in its relations with its citizens—were instrumental in the rise of sectarianism in Iraq. In fact, the post-US invasion political system in Iraq was built to reflect and consolidate sectarian cleavages. Key posts in the country were divided along sectarian and ethnic divisions, reflecting the shifting balance of power between winners (Shia Arabs and Kurds) and losers (Sunni Arabs). The sectarian policies of Hizb al-Daawa, especially under former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, ruined any possibility of establishing a state for all its citizens. In Syria, the use of massive force by Bashar al-Assad’s regime to suppress the 2011 protest movement, and Iranian and Iraqi support for these drastic measures, led to the emergence of regional sectarian axes.

During these turbulent times, the state in the Arab East moved from being a weak one—wherein a government could provide poor quality public services to its citizens but still function as a sovereign entity in regional and world politics, while exercising a monopoly on violence within its territories—to a failed or collapsed state. Failed states hardly supply any public services, lack security, and discriminate against different groups of citizens.v A collapsed state loses control over huge parts of its territories and the provision of security becomes private. Within these conditions, sectarian armed militias emerge and thrive.

Marginalized and vulnerable communities seek protection and solace from private groups, such as militias, because the state can no longer provide security and public services. The state also loses legitimacy and cannot function as an arbiter between different social forces. Trapped in a vicious circle and pitted against each other, sectarian groups seek support from external sources. Here the lines between local and regional conflicts become blurred. The borders between failed or collapsed states are also compromised, wherein communities from the same sect support each other with little respect to national borders. This leads to the rise of transnational sectarian identities wherein Iraqi Shia, for example, see themselves closer to Iranian Shia than to Iraqi Sunnis, and vice versa. National identities crack as a result: people cease to identify themselves as Syrians or Iraqis, but as Sunni and Shia. They no longer pay allegiance and loyalty to the state but to a higher transnational authority. Historical forces here work in a retrospect or in a reverse mode, regressing from nation-states to religious empires.

Remedies

If the Middle East region is to overcome the sectarian dilemma, it is imperative that we cease to characterize sectarianism in religious or ideological terms or to refer it back to the early days of Islam. We must instead understand it in its correct modern context as a political, economic, and geostrategic conflict that can be resolved. It behooves us to address its manifestations as conflicts for wealth and power, though these are concealed in sectarian terms used by the elite to manipulate and mobilize the masses. We must also deal with the sectarianism that resulted from other problems in the region such as the Palestinian struggle and foreign interference, including that by Iran.

A clarification also needs to be made between Sunnis and IS, which is a Sunni extremist organization. The 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index surveyvi conducted by the Doha-based Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies shows that an overwhelming majority (92 percent) of the Arab public, the majority of which is Sunni, has a negative view of IS, with only 5 percent expressing “positive” or “positive to some extent” views. Crucially, favorable views of IS were not correlated with religion: respondents who identified themselves as “not religious” were just as likely to have favorable views of the organization as those who identified themselves as “very religious.” Similarly, no relationship could be found between respondents’ opinions of IS and their views on the role of religion in the public sphere. In other words, public attitudes toward the organization are defined by present-day political considerations and not motivated by religion.

This distinction between religiosity and political considerations reflects the complicated nature of Arabs’ ideational positions. As the survey shows, there was parity in the opinions about the Islamic State between those who agree on separating religion from the state and those who reject the separation. While only 5 percent of those who agree with the separation have varying positive views of IS, only 4 percent of those who reject the separation do. In other words, 95 and 96 percent of the two categories have negative views of the organization.

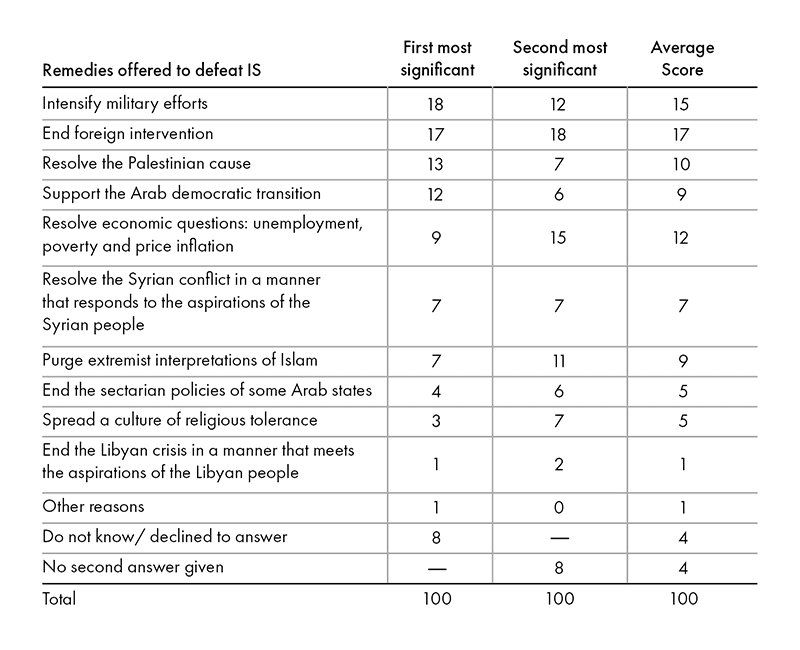

Equally important, the Arab public offers a diverse set of remedies when asked to suggest the best means by which to combat the Islamic State. When given the chance to define their first and second preferences for the means to tackle IS in particular, and terrorist groups more broadly, direct military action was the most widely selected first choice by 18 percent of respondents; an end to foreign intervention in Arab countries was selected as the first choice by 17 percent of respondents; and 13 percent proposed resolution of the Palestinian struggle as their remedy of choice. (See Table 1 below.)

Table 1. Proposed remedies to IS/terrorism more broadly, first choice made by respondents.

Rebuilding a strong national state is also key to resolving sectarian conflict in the Arab Middle East. A strong national state does not mean a repressive state, which was responsible for this sectarian mess in the first place, but a state that respects human rights and the rule of law. However, for that to take place the state must be strong enough to retain its monopoly over the means of violence. No militias or armed groups can hence be allowed to challenge the state, which must reign supreme in this regard. Rebuilding the state should therefore focus on the centralization and institutionalization of power. Centralization of power means disarming militias and disallowing parallel authorities. Institutionalization of power means establishing checks and balances so that the state does not again become a tool of control in the hands of the few. It must rather become a neutral arbiter between the different social forces.

Rebuilding the state, empowering it, regaining public confidence in it, and enabling it to perform its key functions go a long way toward weakening sectarian militias. As long as the state is weak, people will rely on militias for protection, security, and social services.

For a strong national state to be built, a Westphalian peace must be established in the Middle East wherein no country can be allowed to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs. Citizen loyalty must only be expressed toward a national state and not for any other transnational authority, be that of a religious or secular nature. Loyalty to the state can be made easier if national governments become more representative and reflect the will of their own people. Democratic regimes are more amenable to resolving conflicts and building collective security regimes. This would allow more resources to be allocated for economic development, without which democracy cannot survive and conflict cannot be ended.

Alternatively, if the state in the Middle East continues to fail and its power continues to diminish, sectarian non-state actors will grow in power while their violent acts will also increase.

i The Obama White House, “President Obama’s 2016 State of the Union Address,” Medium, January 12, 2016, https://bit.ly/2DWr8bP

ii Bernard Lewis, “The Return of Islam,” Commentary, Vol. 61, No. 1 (January 1974): pp. 39-49.

iii At the time when Iraq was supporting the Marxist rebels in the province of Dhofar, Oman, Iran under the shah supported the pro-West Sultan’s Armed Forces. The shah sent an Iranian army brigade numbering 1,200, with its own helicopters, to assist the British-led Sultan’s Armed Forces in 1973. In 1974, the Iranian contribution was expanded into the Imperial Iranian Task Force, numbering 4,000. This support led eventually to the final defeat of the rebels in 1975.

iv This term was originally used by King Abdullah II of Jordan following the US invasion of Iraq. See Robin Wright and Peter Baker, “Iraq, Jordan See Threat to Election from Iran,” The Washington Post, December 8, 2004, https://wapo.st/2zOqP3s.

v Robert I. Rotberg, State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror (Washington, DC: World Peace Foundation/Brookings Institution Press, 2003), pp. 5-10.

vi All results, charts, and tables can be found in the 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index, https://bit.ly/2s1fVTm.