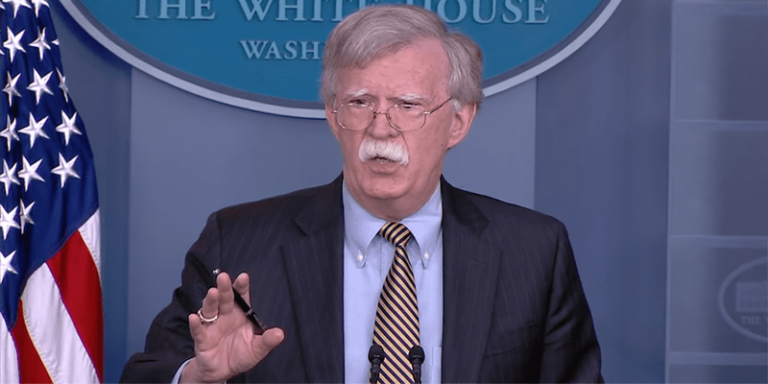

Tell-all books like Fear, Fire and Fury, and Unhinged have chronicled a White House in a perpetual state of chaos. The purported dearth of direction and leadership there and in the national security apparatus has undoubtedly left a vacuum to be filled. This unstable landscape allows National Security Advisor (NSA) John Bolton—a savvy navigator of Washington bureaucracy—a more assertive role in policy-making decisions; he has the capability to be a steely vessel through which the president can execute his gut instincts and nationalist agenda. While Bolton has already angled to use the National Security Council (NSC) to further his own worldview, shaping the Trump White House’s policies will not go unchallenged. Indeed, career civil servants with sober perspectives on world affairs have already indicated that they must act as rational stewards of this administration’s policies, constraining the worst instincts of a mercurial and often vindictive president. This bureaucratic guardrail is viewed by some as nefarious—so much so that Bolton, President Donald Trump, and others have dubbed these civil servants part of the “deep state.”

However, it is not just the career staffers who might stand as obstacles to the realization of Bolton’s policies. Other cabinet members—particularly Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defense James Mattis—may split with Bolton and thwart his agenda. Even President Trump, with his transactional approach to policy, might discard ideology for gain when he sees fit. How effectively Bolton steers the NSC through the gauntlet of Washington’s bureaucracy will go a long way in determining US policy toward the Middle East and North Africa.

What Is the National Security Council?

To understand Bolton’s role as the national security advisor, it is important first to understand the organization he leads and its role in executing policy. The NSC was created for one purpose: “to advise the President with respect to the integration of domestic, foreign, and military policies relating to the national security” so that all government entities work in coordination to further the president’s goals. The council was never intended to be a policy formulating entity; rather, it was supposed to be a collective that oversees the execution of the president’s national security priorities. Over the years, however, the NSC’s role has varied—and usually grown—from one administration to another.

Each administration shapes the NSC differently, but there have been marked differences between those that were generally successful and scandal free and those that were neither

Each administration shapes the NSC differently, but there have been marked differences between those that were generally successful and scandal free and those that were neither. The infamous Iran-Contra Affair, according to a 2011 report by the Congressional Research Service, partly took shape from the halls of the White House due to the lack of “a strong and efficient [NSA] and staff.” It affirms, “If the President himself does not provide detailed direction” to the NSC and his top advisor, the council only stands to be more dysfunctional, devolving into an echo chamber that produces poor policies.

On the other end of the spectrum, the individuals generally considered successes in running the NSC—like former NSAs Brent Scowcroft under President George H.W. Bush and Anthony Lake and Samuel Berger under President Bill Clinton—were deft managers who navigated the bureaucracy well and largely avoided the clashes with secretaries of defense and state that plagued other administrations. Indeed, it is important that the president have an effective and clear-headed NSA to oversee the bureaucratic processes because if a president loses confidence in those processes, or they are mired in infighting, he or his top officials may turn inward, thus circumscribing national security decisions within the purview of a small cadre of trusted advisors. If this happens, policy-making becomes unchecked and could render the White House and NSC largely dysfunctional with grave consequences for the United States—and especially for the regions where ill-advised policies are carried out. To be sure, the Iran-Contra Affair was damaging, but other NSC-backed plans proved much worse for the Arab world. Historical records indicate that the decision to invade Iraq was being discussed by the George W. Bush NSC just days after his inauguration. A few years later, the NSC conspired with the State Department to back the Palestinian Fatah party in an attempt to wrest power away from Hamas, after the latter’s electoral success in 2006.

Guardrails Against the Bolton Agenda

Two things are abundantly clear about John Bolton: he is not as weak or incompetent a leader—despite his very real flaws—as some other NSAs may have been, but he is also not averse to the intra-bureaucratic clashes that may place him at odds with other key members of the administration. Since his days at the State Department, Bolton has been extremely distrustful of career diplomats at Foggy Bottom and throughout the massive Washington bureaucracy. There are stories of Bolton shunning analyses that contradict his preconceived notions and berating the analysts he thought were usurping his policy proposals. Now, however, as head of the NSC, Bolton is responsible for consolidating information from throughout the national security apparatus to deliver sound recommendations to President Trump.

Bolton could work around opponents of his preferred policies, freezing them out of the decision-making process

With his history of political maneuvering, however, Bolton could very well work around opponents of his preferred policies, freezing them out of the decision-making process. Though he and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo share similar policy preferences regarding various issues, Pompeo is regarded as nominally better at listening to career diplomats and considering their advice—much of which runs counter to Bolton’s bombastic ways. With Secretary of Defense James Mattis, the ideological clashes over policy are less subtle. Mattis, once removed from a high-level Obama Administration position for his hawkish views, has turned out to be comparatively more dovish under the Trump Administration. Like Bolton, he supports limited strikes in Syria and has advocated for continued troop presence there. However, the clash between them may occur if the administration has to decide whether to carry out strikes on Iranian positions in Syria or on nuclear infrastructure in Iran itself. Mattis is likely to take a more cautious approach, appreciating well the unknowns involved with a first-strike policy, while Bolton may have another opinion entirely.

When the State or Defense Departments stand opposed to Bolton’s policy proposals, the war for the president’s ear will be fought not by calm, rational considerations but by playing to the president’s instincts and making the most emotional—not the most logical—argument to Trump. Clashes of this nature would unfold on the airwaves and in newspapers; whoever can best appeal to Trump’s sense of nationalism and personal success would likely win. Bolton’s credentials as a star of conservative punditry—credited as the reason he was tapped to be the national security advisor—and his reputation as a wily political operator, combined with his greater proximity to President Trump, all make him well positioned to push his personal foreign policy agenda for the Middle East.

Further, because Bolton is most distrustful of the so-called deep state yet ambitious enough to pursue his long-standing personal agenda, he could turn the NSC inward, crafting policy with an insular cadre of his closest confidants if he feels he is being blocked by the bureaucrats. Bolton has been eclipsed by the bureaucracy in the past, and this will spur him to take precautions to avoid such a scenario again. For example, during his tenure in the George W. Bush Administration, Bolton was repeatedly frozen out of discussions about Washington’s strategy toward Libya’s then-dictator, Muammar Qadhafi, for fear he would undermine the administration’s efforts to de-nuclearize Tripoli. If Bolton, a seasoned survivor of Washington politics, suspects he is being circumvented by others, he could further tighten his control on the flow of information to the president and place his ambitions on the forefront.

Bolton’s Priorities and Influence in Middle East Policy

With a long history of political and think-tank work and extensive media appearances, there is no shortage of information about what John Bolton thinks about foreign policy. If he is successful in effectively challenging the bureaucracies in the military, diplomatic, and intelligence agencies and securing his political objectives, Bolton could push the White House to adopt the following policies toward key issues in the Middle East and North Africa.

Regime change in Iran has been Bolton’s number one target for years and he has been pivotal to President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA

Regime Change in Iran. Iran has been Bolton’s number one target for years; he has repeatedly called for regime change there. He is a frequent participant in conferences hosted by one of the most despised groups of dissident Iranians, Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, who have called for armed revolution against the mullahs. Bolton also has been pivotal to President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Even now, when given the opportunity to discuss the topic more freely before sympathetic audiences, Bolton reiterates the rhetoric of “hell to pay” for any transgression by the Iranian regime. He is cavalier about the use of force and is less interested in the details of a potential military effort to decapitate the regime, although such consequential action could very well rival the devastating US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Pushing Back Against Iranian Hegemony. Though the idea is not foreign to this White House, eradicating Iranian influence throughout the region will likely take an even higher priority on Bolton’s agenda. He has already said that US troops will remain in Syria until not only the so-called Islamic State is purged from its territory, but also until Iran and its proxy forces leave Syria. If this policy is implemented, one can suspect that a similar policy would apply to neighboring Iraq. The difference between Bolton and his predecessor H.R. McMaster, or his colleague Secretary Mattis, is that Bolton may try to convince the president that military force is necessary to uproot Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and Lebanon’s Hezbollah personnel from Syria. Further, any escalation in Syria and/or Iraq would most likely push Tehran to retaliate, a decision that could escalate US-Iran tensions to the levels of the late-2000s in Iraq when Iranian proxies killed many US service members.

For Yemen, Lebanon, and even North Africa—where Iranian influence varies from entrenched to disputed—Bolton will likely push for a more confrontational approach against Tehran. Like President Trump and Secretary Pompeo, he supports Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in their operations against Yemen’s Houthi rebels, ensuring that the two Gulf countries feel emboldened to continue the disastrous war. In Lebanon, where the political situation is perpetually unstable, Bolton may push the president to support the efforts of the Sunni regional powers to wrest power away from Iranian-backed Hezbollah, which is firmly entrenched in the Lebanese political system. But a more aggressive US strategy in Lebanon may worsen an already fragile situation. Finally, Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, and others in North Africa have warned that Iran, through Hezbollah, is seeking to infiltrate their borders and dominate the Sunni-majority states of North Africa. If Bolton subscribes to this line of thinking and convinces the president that this region is yet another arena in which Washington must confront Iran, money and weapons could flow to those states. In addition, the ruling parties could crack down on, or further ostracize, their small Shia communities.

Bolton’s appointment further entrenches US bias toward Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s positions against the Palestinians

Supporting a Right-Wing Israeli Agenda. The current administration had supported right-wing Israeli policies before Bolton came on board, but his appointment further entrenches US bias toward Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s positions against the Palestinians. In the past, Bolton advocated for even more extreme policies, like urging that neighbors of the occupied Palestinian territories, Egypt and Jordan, absorb Gaza and the West Bank into their respective borders. Bolton’s presence in the White House may have emboldened the president to consider floating the idea to Arab leaders of a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation, one that is ardently opposed by many in the region.

Bolton’s dual disdain for Palestinians and his unabashed belief in US supremacy also make him an avid opponent of any international entity the Palestinians might use to challenge Israel to gain their human, civil, and political rights (e.g., the International Criminal Court and the UN Human Rights Council) and to maintain humanitarian aid from the UN Relief and Works Agency. Indeed, between his influence and that of Nikki Haley, during her tenure as the US ambassador at the United Nations, the president has withdrawn US support and economic aid that provide humanitarian assistance to millions of Palestinians. Bolton’s announcement that the United States would be withdrawing from the “optimal protocol” for dispute resolution, established by the 1961 Vienna Convention of Diplomatic Relations, clearly illustrates his deeply disdainful treatment of the Palestinian leadership and its attempts to garner the international community’s support. The decision, according to Bolton, is a direct response to the “so-called state of Palestine,” as he derisively called the occupied territories, because its leadership appealed to the International Court of Justice regarding the US decision to move its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, saying that it violated international treaties. Indeed, Bolton has long shared with many in the far-right camp in Israel a strong antipathy for Palestinians and uncritical support for the “greater Israel” narrative. His positions would only further intensify the White House’s antagonistic positions toward the Palestinians.

In sum, Bolton, who has long been considered a fringe player, even in US conservative circles, is highly ambitious in exerting US strength in the Middle East. Many career bureaucrats and even other high-ranking White House officials may push back and try to minimize his more militaristic or ill-advised impulses. But if the wily Bolton is able to raise his NSC above the Washington bureaucracy to champion his aggressive vision of US policy toward the Arab world, the implications could be dire for the entire Middle East.