Amid growing concern about backsliding democracy and deteriorating freedom in much of the world, the Middle East stands out.

While never a paragon of democratic advancement or respect for human rights, the region, through the events of the Arab Spring that began in 2011, inspired hope that change might be afoot. Indeed, in the first two years of the wave of uprisings and protests that roiled several countries, the region experienced upticks in personal and political freedoms.

Today, however, much of that progress has been challenged or reversed. According to the human rights organization Freedom House, the Middle East and North Africa, despite a few bright spots, is the least free region in the world today and the situation has deteriorated significantly in the years of the post-Arab Spring. Factors in this decline include lack of political inclusiveness, economic cronyism and corruption, political violence by state and non-state actors alike, and sharp curbs on freedoms of expression, belief, assembly, religion, and the rule of law. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Human Rights First, and other leading organizations have all documented the serious erosion of human rights in the region across a wide range of categories in the last few years.

Repressive governments in the region learned from the Arab Spring that any political opening can lead to volatility and a threat to the existing order.

Lack of basic freedom and democratic governance is a serious challenge to development and stability on many levels. As the Arab Human Development Reports made clear, “securing fundamental rights and freedoms” is vital to solving the Arab world’s endemic problems of political stability, extremism, and faltering economies.

Demands for democracy, wider political space, and guarantees of basic human rights have been turned aside by more effective authoritarian responses for now, but they are unlikely to be held in check indefinitely. Even though the Arab Spring may have stalled, the factors that helped bring it about remain in place.

The Authoritarian Pushback

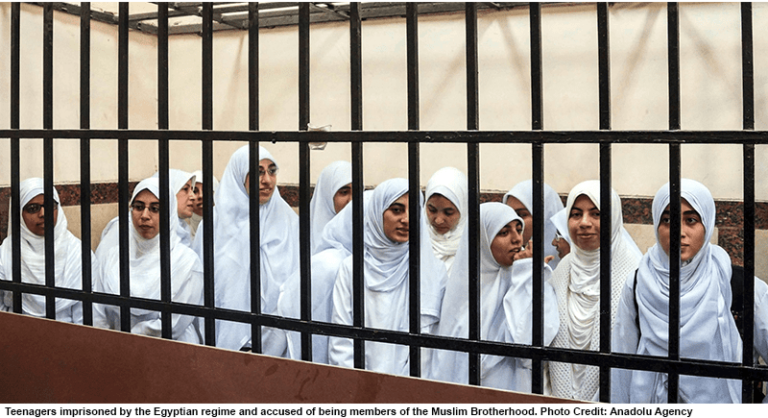

Repressive governments in the region learned several lessons from the Arab Spring, the most important of which was that any political opening, however narrow and closely managed, can lead to volatility and a threat to the existing order. Therefore, any such openings must be discouraged where possible or crushed if necessary. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi applied this lesson ruthlessly during his reelection bid last March, which he won with some 97 percent of the vote. The election was marred by irregularities and took place only after all other plausible candidates had been eliminated through threats or intimidation. Repression has intensified since the 2013 coup that installed Sisi in power, including wholesale repression of civil society and reports of extra-judicial killings and instances of torture.

Elsewhere, governments have employed both carrots and sticks. In Saudi Arabia, for example, some cultural loosening has substituted for meaningful political liberalization; cinemas have been allowed to open, women have been granted the right to drive and vote in municipal elections; and strictures on the public mixing of sexes have been eased. But the autocracy is still in place and decision-making authority remains concentrated in very few hands, notably those of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, while crackdowns on dissent and political and social activism continue. For example, since mid-May, seven women activists who spoke out in favor of lifting the ban on female driving were rounded up and detained by the authorities. Similar practices prevail in most of the Gulf countries, as observers such as the Gulf Center for Human Rights have documented.

Governments in the Middle East have turned to foreign adventurism to deflect attention from their own failings and put off demands for political change.

Iran, too, has experimented with looser enforcement of female dress codes and social norms, but the clerical authorities remain firmly entrenched. The government was very quick to crack down early this year—albeit without the violence used to quell the 2009 Green Movement—on widespread protests provoked in part by disclosures about government spending on military activities abroad, especially in Syria.

In the last few years, governments in the Middle East have also turned to foreign adventurism to deflect attention from their own failings, build a semblance of public support, and put off demands for political change, much as regimes have used the Arab-Israeli conflict in the past. Examples include the Saudi-UAE intervention in Yemen, involvement of various states in the Syrian and Libyan conflicts, the rumblings in Egypt about using force to stop the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam if necessary, and, to some extent, the region-wide hype about Iran and the Islamic State.

In addition, leaders across the region are attempting to modernize authoritarian practices through increasingly sophisticated use of information technology and data gathering while enhancing control of information and communications technologies. Recent years have seen strenuous efforts to restrict online discourse and troll critics, often through fake online accounts and Twitter guises, while making more sophisticated overt use of social media themselves. Governments have also attempted to gain access to identifying data on app users and to ban or restrict communication services such as Skype and WhatsApp that may challenge a government’s ability and capacity to monitor and control.

Many of these efforts are aimed at a key and growing demographic of users: young people. Governments are counting on the notion “that youths can be permanently deactivated.”

Is the End of the Authoritarian Bargain Nigh?

Clearly, governments in the region worry that youth populations, if left unchecked, will once again become a powerful driver of demands for political and social transformation. And with good reason. Youth populations in the Arab states, which helped fuel revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, continue to grow as a considerable percentage of the region’s population. The think tank YouthPolicy.org estimates that young people are the fastest growing segment of Arab countries’ populations, noting that “some 60 % of the population is under 25 years old, making this one of the most youthful regions in the world with a median age of 22 years compared to a global average of 28.”

Despite Trump’s disdain for human rights and democracy promotion, the US continues to play an important role in advocacy for human rights and democracy abroad.

This is important for a number of reasons. As Kristen Lord, president of the global development and education organization IREX, has written,

Surging populations of young people will have the power to drive political and social norms, influence what modes of governance will be adopted and the role women will play in society, and embrace or discredit extremist ideologies. They are the fulcrum on which future social attitudes rest. These young people could transform entire regions, making them more prosperous, more just, and more secure. Or they could also unleash a flood of instability and violence. Or both. And if their countries are not able to accommodate their needs and aspirations, they could generate waves of migration for decades.

Demands of Middle Eastern youth today and, in fact, the demands of Middle East populations in general, remain largely unaddressed and very similar to what they were in 2011, when the Arab Spring began: social justice, jobs, dignity, and greater social and personal freedoms. The uprisings exposed the fact that the traditional “authoritarian bargain”—in other words, governments’ ability to provide economic goods, jobs, and other forms of patronage and favors if citizens accept curtailment of political rights and personal freedoms—is no longer operative. Faltering economies, poor quality public services, and the lack of institutional and political accountability have thrown the failings of governance into high relief. Widespread use of social media and other technological platforms has made it easier than ever to access unfiltered information from a variety of sources and to criticize governments before a wide audience. It also enables activists to communicate politically and organize quickly, making it harder to keep closed systems closed. Indeed, as Moroccan scholar Hicham Alaoui remarks, “youths and activists learn over time, and adopt more sophisticated strategies in response to state repression. The strategic occupation of public spaces, the use of social networking technologies, and mass outreach efforts will eventually outpace regime efforts to control them.”

Pressure from growing youth populations is not the only factor working against authoritarianism in the Middle East. Many countries of the region are seeing the growth of middle classes, which tend to prize political voice and rule of law as guarantors of their economic prospects. Likewise, gradual improvements in gender equality in both politics and the workplace have added to pressure for more political openness. The erosion of oil prices, which in many countries financed the authoritarian bargain in the first place by laying the groundwork for the rentier economies of the region, has placed new demands on autocratic rulers to adapt.

Numerous demographic, economic, social, and technological drivers are already at work that will push renewed demands for respect for human rights in the future.

Finally, the example of democratic changes in some countries in the region—such as in Tunisia and Iraq, where genuine nationwide elections took place earlier this month—can highlight the shortcomings of authoritarian systems elsewhere and create demand for democratic change.

Democracy, Human Rights, and US policy

Despite President Trump’s well-documented disdain for human rights and democracy promotion, and the mixed signals sent by senior members of his administration, the United States continues to play an important role in advocacy for human rights and democracy abroad, and the State Department under new Secretary Mike Pompeo may prove more open on these issues than his predecessor Rex Tillerson. When Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) questioned Pompeo during his confirmation hearings in April, Rubio pressed him on democracy promotion and human rights efforts, offering a full-throated endorsement of both. Pompeo agreed in unambiguous terms, promising to make them a priority at State and affirming that “our effectiveness at doing that is an important tool of American foreign policy.” He added that “America’s vision, a democratic vision,” is very important in countering authoritarian narratives from China. Rubio also referenced Russia in his questioning as one of the greatest challenges to American foreign policy, highlighting a traditional concern about democracy and human rights.

In addition, despite the many threats to cut resources for democracy promotion and to downgrade it as an element of US foreign policy, few such cuts have actually been enacted. For example, as Tom Carothers of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has noted, the omnibus appropriations bill passed last year for FY 2017 “basically straight-lined [i.e., deleted] the international affairs budget and included a 40 percent increase in the State Department’s Human Rights and Democracy Fund.” An effort earlier this year to drastically cut funding for the National Endowment for Democracy has failed, so far, to make much headway. This is mainly due to an energetic congressional constituency for democracy promotion, as exemplified by Senator Rubio.

But democracy promotion and the advancement of human rights in US policy are also due to the dedication of many in the human rights bureaucracy at State, USAID, and diplomats in the field and elsewhere who take the mission seriously and continue to pursue it, both because they believe in it and because they see important US interests at stake. A new strategy on democratization and human rights, linked to Pillar IV of the administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy, is in the works, which recognizes democracy and human rights as fundamental American values and their effective promotion as critical to US interests. If this strategy is pursued with enough political will, it could provide an effective counterpoint to the authoritarian narrative worldwide and constrict the ability of repressive governments, including a number of American allies in the Middle East, to act with impunity in the belief that the United States would not hold them accountable.

The End of the Beginning

With authoritarian retrenchment holding the whip hand in the Middle East for now, it is difficult to imagine a new wave of popular uprisings churning through the region anytime soon. Nevertheless, numerous demographic, economic, social, and technological drivers are already at work that will push renewed demands for political liberalization and respect for human rights in the future. Neither governments in the region nor the United States can afford to remain complacent.